![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Middlemen, Marketplaces, and Maps

“This is the only Tibetan News Paper published in India, it is read by all the high Lamas, Officials, and leading traders in Tibet, Sikkim, Bhutan, Darjeeling, Northeast Assam, Kashmir Ladakh, Almora, Kulu Himachal Pradesh, Gharwal & Nepal.”

From a brochure listing advertising prices in

the Tibet Mirror for September 1954

Trade and the Tibet Mirror

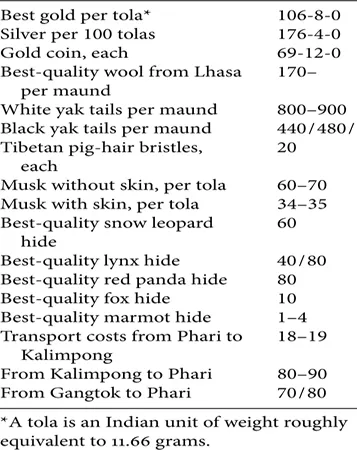

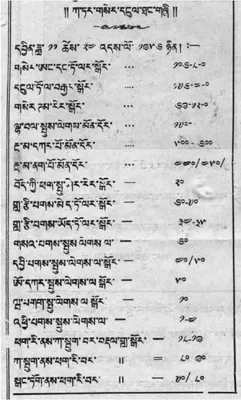

The Tibet Mirror (yul phyogs so so’i gsar ’gyur me long), a twentieth-century Tibetan-language newspaper published in Kalimpong, had commodity listings in nearly every issue of the newspaper from its start in 1925 until its demise in 1963. These listings gave its readers an idea of what the “market prices in Gold and Silver from Calcutta” looked like, as well as the prices of common items brought from Tibet to Kalimpong. The newspaper clipping below is from the November 24, 1956, edition of the Mirror and lists prices for various commodities traded between Lhasa and Kalimpong (figure 5). The items were priced in rupees per mon do (maund, a bulk weight of approximately 40–80 kg) and included the following prices per maund: white yaks’ tails (800–900 Rs, about US$167–188), black yak tails (440–480 Rs, $92–100), Tibetan pig-hair bristles for hair brushes (20 Rs, $4), musk without skin (60–70 Rs, $13–15), best-quality snow leopard fur (60 Rs, $13), best-quality fox fur (10 Rs, $2), and best-quality marmot fur (1–4 Rs, $0.20–0.84). Mule caravan transport costs were also listed: the journey from Phari to Kalimpong cost 18–19 Rs ($4); Kalimpong to Phari 80–90 Rs ($17–19).

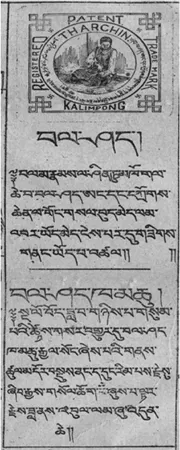

The Tibet Mirror was established in Kalimpong in 1925 by Gergan Dorje Tharchin.1 Tharchin was a Christian missionary from Kinnaur, in eastern Himachal Pradesh, popularly named Tharchin Babu (babu is a term of respect for men in several South Asian languages). His newspaper had a small but far-reaching distribution, selling approximately 200–500 copies from Amdo (northern Tibet) to Assam (northeastern India) until 1963. It was transported by the same mule caravans that carried the yak tails and musk listed in the clipping above and was disseminated to medium- and large-scale merchants, traders, and intellectuals living in the towns dotted along the trade routes (Fader 2002: 282). The newspaper provided world and regional news, children’s stories, a science section, proverbs, and maps; specific examples include advertisements for wool carders and for “Asiatic Soap,” articles about trade disputes, articles about bad weather damaging the wool in the caravans, and notices announcing changes in state trading policies (see figure 62).

TABLE 1. Market Prices in Gold and Silver from Kolkata, November 24, 1956.

FIGURE 5. List of commodity prices in the Tibet Mirror, November 24, 1956. Tharchin Collection, Columbia University Libraries.

These columns about trade in the region, as well as regular listings of trade prices, demonstrate that such “transnational” trading practices have long permeated the economic life of the towns along the Lhasa–Kalimpong trade route. Trading news and various types of information—political, economic, and cultural—traveled along the route with the wool itself; Tibet at this time was certainly not remote in the way that Europeans may have believed, and was in fact very much part of a regional and international economy. To take one example, yak tails—particularly white ones—were (and are) of quite high value because of their use as Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist ritual implements, as flywhisks, and as wigs and Santa Claus beards in Europe and the United States. As a result of North American trade embargos on China in the 1950s, Tibetan exports such as yak tails began to gather slightly more international demand around this time. According to an article titled “Shortage of Yak Tails Worries Santa” in the University of British Columbia student newspaper in 1958, “One Mrs. Cox, who runs a costume supply shop in town, states she has only one Santa Claus suit in stock and that she has had to raise the rental price from $6.50 to $7.50” (Ubyssey 1958: 5). Today, yak tails remain a valuable commodity; costumes for the Orcs, characters in the Lord of the Rings films, were made of yak hair, and Santa Claus beards made of white yak tails fetch upwards of US$300.

FIGURE 6 An advertisement for Tharchin’s brand of bal shad (wool carding combs), which were manufactured in Kalimpong (note the Urdu, Hindi, and Tibetan on the stamp). Tharchin Collection, Columbia University Libraries.

A deeper understanding of the social and geopolitical history of trade between Tibet, India, and Nepal—as well as trade connections to such larger powers as Britain and the United States—is integral to how we understand the region’s present economic shifts. While geopolitical strategies have affected the direction of the trade routes—for instance, the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British push to “open” Tibet as a market for goods and development and the Chinese “Develop the West” campaign (Cn. Xibu da kaifa) of recent history—traders themselves will often have qualitatively different experiences of such changes.3 Plans to “open” a region, route, or border ignore the fact that the territory has almost never been completely “closed” to actual inhabitants living and trading in the area in the first place. What’s more, this choice of words—to “open up” or to “close off” an entire region or route—should not be ignored geopolitically. States or hegemons are seen here as the ones in control of access to the land, not the individuals or communities who live in or move through these areas.

This chapter lays out the historical background to the political, social, and economic climate along the trade route between Lhasa, Kalimpong, and Kathmandu and is supplemented by ethnographic accounts from older traders who were operating prior to and just after the closing of Nathu-la in 1962. I focus on snapshots of specific moments that are significant to the rest of the book, moments that raise questions about competing spatial representations, social mobility, and the strategic directionality of trade. These snapshots take place during roughly three periods. The first period coincides with the British strategy to map the Himalayas as an adjunct of India and to “open” the Chumbi Valley in Tibet for trade between the late eighteenth and early twentieth centuries. The second period covers the peak and decline of the Tibetan wool trade, the resulting stratification of traders, and the introduction of new kinds of transport along the trade route in the mid-twentieth century. The third period follows the rerouting of the Tibet–India trade through Nepal after the 1962 Sino-Indian border war, culminating in a ghost story that appears to link border disputes from the past with the more contemporary drive to increase Sino-Indian border trade.

The intertwining of economic and geopolitical strategies is a major part of the larger historical picture of macro world histories. Trade cannot be studied as a phenomenon in isolation from state policies, nor can the practices and lives of traders, which often reveal a very different trajectory from those policies. A trade route is never simply “there,” displaying a simple, recognizable shape over the course of centuries; groups of people may follow the same paths, but there is always more than one route or conception of the route being forged at a time. The Himalayan landscape has always been molded, reformed, argued over, rerouted, and produced by people. This is a dynamic story of fixity and movement, of trade restrictions established by state powers and how various competing parties respond by maneuvering around them. I hope to show, through historical and contemporary accounts, “the dynamic connections between political powers and geographical knowledges of different sorts” (Harvey 2001: 233).

Mapping the Himalayas: British Designs on Tibet

Tibet has often been portrayed by Western travelers and scholars as remote and otherworldly. Even in the March 2008 media reports on anti-Chinese unrest in Tibet, the region was depicted as only very recently opening up to the outside world. Take for instance headlines such as “In Remote China, Tibetans Break Silence” and “Why Is Remote Tibet of Strategic Significance?” (Anna 2008; Reuters 2008). Tibet has, however, been part of a vibrant network of inter-Asian caravan routes ever since the seventh century, when Indian scholars introduced Buddhist texts to Central Asia and China, and pilgrimage routes paralleled the tributaries of what historians now consider the northern Silk Road (Klimburg 1982: 33). Tibetan musk was even purportedly traded between India and the Roman Empire (Beckwith 1977). Rather than a single “road,” these numerous trading and information networks ramified in several directions between the seventh and tenth centuries: textiles and gems came from northern China, tea arrived in the form of bricks from Yunnan, raisins came from Khotan, seashells from south India, and pashmina shawl wool from Ladakh.4

Although trade has risen and fallen throughout inner Asia over the centuries, it peaked significantly in the early to mid-seventeenth century, when trans-Himalayan trade coincided with several geopolitical factors—in particular, the rise of Mogul India and the establishment of Western maritime powers such as the Dutch East India company (Boulnois 2003: 135, 137). In 1642, for instance, the fifth Dalai Lama “presided over a large Tibetan state from Kham to Ladakh and the development of Lhasa as the administrative, religious, and commercial capital,” while the rise of the Moguls made the Malla kingdoms of Nepal prosperous; they acted as middlemen for trade between India and Tibet (Boulnois 2003: 138).

The British East India Company became interested in Tibet in the late eighteenth century, around the time the monopoly started to show signs of slowing down and subsiding. As the company started to lose its grip on trade in Asia, it was forced to think about a locational shift; it thus began to specialize in overland textile trade through the “blank” areas of inner Asia (Arrighi 1994: 248). When the Gurkha conquest of Nepal shut off trade between Tibet and India in 1769, the company made an explicit move to introduce British commodities such as Manchester textiles and Indian indigo to the potential new market of China via the “back door” of Tibet (Cammann 1970: 144–45).

The task, then, was for the British to explore the “the nature of the road between the borders of Bengal and Lhasa” to prolong their economic and territorial expansion (Bishop 1989: 82). In 1774, Warren Hastings (governor-general of British India from 1773 to 1785) asked George Bogle, the first British envoy to Tibet and Bhutan, to send a team to investigate the area. Bogle was given a list of items to procure, including pashmina goats, two yaks, walnuts, rhubarb, ginseng, and any animals that he happened to find “remarkably curious” (Bishop 1989: 30). According to Peter Bishop’s account of the history of Western spatial representations of Tibet, while Tibet had a general location (somewhere between China, India, and Central Asia) in the British imagination at that time, it had very little shape (Bishop 1989: 30). Bogle’s initial meetings in Tibet were short-lived, partly due to his untimely death by drowning, but British interest in “opening” Tibet for commercial purposes was taken up again a century later. Echoing earlier trade reports from the East India Company, Francis Young-husband, the leader of the 1904 British invasion of Tibet, recalled that in 1873, “besides tea, the Bengal Government thought that Manchester and Birmingham goods and Indian indigo would find a market in Tibet, and that we should receive in return much wool, sheep, cattle, walnuts, Tibetan cloths, and other commodities” (Younghusband 1910).

Hand in hand with the need to gain scientific knowledge about the flora and fauna of the “unknown” region beyond the existing British empire was the need to create a uniform, structured survey of the territory: to “know” India, minus its diverse specificities, of course (Edney 1997: 324). At the same time that we are reminded about the power relations involved in the actual practice of state- or government-led exploration and the subsequent creation of a map of a region or a route, there seems to be a certain state-based conjuring taking place, entangled with the magic and mystery of exploring the unknown. “What seems crucial here is what this tells us about the state; how it needs this theater with its magic, but needs it disguised as science, and how important the domination of nature is to such theater” (Taussig 2004: 198). In other words, the exploration and cartographic representation of Tibet often tells us more about the establishment of the shape of the British empire than it does about the physical landscape of the region.

Although the nineteenth-century exploration and geographical mapping of the Himalayas through the British Great Trigonometric Survey is already widely documented, I refer to it here briefly, as cartographic knowledge is often an elite and uneven form of power.5 The Himalayas, as a major part of the survey, began to be seen as connected to India and therefore came to be viewed by the British as a “rational” and unquestionable part of the British geography (Bishop 1989: 89). Attempting to attach Tibet to the map of British India, motivated in part by fears of Russian expansion during the period known as the “Great Game,” the British colonial authorities harnessed spatial knowledge from inhabitants in the areas where surveys were undertaken, somewhat ironically mapping the “new world by erasing local histories” that were dependent on “local knowledges” (Pickles 2003: 119).

In 1863, the Royal Geographical Society clandestinely trained and sent out Indian and Sikkimese surveyors into Tibet (central Tibet followed an isolationist policy in the nineteenth century, not allowing foreigners into its territory). The surveyors were disguised as traders and given special mapping instruments that had to be concealed; surveyors used Buddhist prayer beads, for instance, while walking along, pretending to murmur mantras for each bead counted. Although they normally have 108 beads, an auspicious Buddhist number, the British instruments were made with 100 beads so that they could measure paces evenly. Buddhist prayer wheels, instead of having scriptures inside, would have slips of paper for recording compass bearings. Compasses and field books were to “look as ‘un-English as possible,’” and mercury was inserted into coconuts for clandestinely measuring altitude (Madan 2004: 95). According to members of the Royal Geographical Society, the pundits’ “labours, if successful, will make … our present stock of Geographical and general knowledge of the vast unexplored countries which lie between India, China and Russia in Asia, most important” (Madan 2004: 143).

The establishment of British Trade Marts in Tibet provides another example of the close relationship between early twentieth-century British geopolitical strategy and British economic advancement. Soon after the survey was completed, an official note stating that the Russians might also want to trade with Tibet was the immediate excuse for the 1904 invasion of Tibet led by Francis Younghusband (Cammann 1970: 147). The invasion was accompanied by the rhetoric of “opening up” the Chumbi Valley (the valley between present-day Sikkim and Tibet) for trade, as if there were nothing there before. This movement toward the “opening up” of the borders between Sikkim and Tibet produced a situation that was actually contrary to this phrase’s connotation of unimpeded, unrestricted mobility. It went hand in hand with the signing of a number of trade treaties put in place in order to establish British Trade Marts in the Tibetan towns of Gyantse, Gartok, and Yatung, as well as the solid demarcation of boundaries between Sikkim and Tibet.6 However, local inhabitants offered some resistance to the trade marts and boundary lines. According to Younghusband’s account:

The “Chief Steward,” the sole Commissioner on the part of the Tibetan Government for reporting on the frontier matter, “made the important statement that the Tibetans did not consider themselves bound by the Convention with China, as they were not a party to it.” He reported further, that the Tibetans had prevented the formation of a mart by building a wall across the valley on the farther side of Yatung, by efficiently guarding this and by prohibiting their traders from passing through. Mr. Korb, a wool merchant from Bengal, had come to Yatung to purchase wool from some of his correspondents on the Tibetan side, who had invited him thither; but the Tibetans prevented his correspondents from coming to do business with him. (Younghusband 1910)

In a 1930 guidebook for British tourists to Tibet, David MacDonald discusses a similar incident. “When the milestones were first erected on the Phari–Gyantse road, the local people invariably destroyed them, alleging they were gods put up by the British to destroy their faith. Only after many years did this belief die out, and even at the present time some of these cairns can be seen scattered over the plain” (MacDonald 1999: 102).

Although the milestone-markers-as-gods allegation is difficult to verify, this incident clearly points to local attitudes toward the construction of the British version of the trade route. British authorities complained that the “imposing of free trade [was] rather difficult because Tibetans were used to their own form of trade rules” (Bell 2000: 256, my emphasis). The trade agencies doubled as administrative units; David MacDonald, a trade officer in Tibet for nearly twenty years, wrote of his duties in Yatung, which “consisted of administering the Trade Mart, caring for the interests of British subjects trading in Tibet, and watching and forwarding reports on the political situation [vis-à-vis China] to the Government of India” (MacDonald 2005: 52–53). Although somewhat cut off from British strategic headquarters in England and India,...