![]()

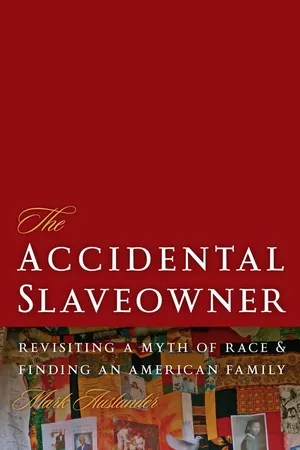

The Accidental Slaveowner

Revisiting a Myth of Race and Finding an American Family

MARK AUSLANDER

![]()

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface and Acknowledgments

Prologue

Part One. Memory, Myth, and Kinship

1 The Myth of Kitty

2 Distant Kin: Slavery and Cultural Intimacy in a Georgia Community

Part Two. Slavery as a Mythical System

3 “The Tenderest Solicitude for Her Welfare”: Founding Texts of the Andrew-Kitty Narrative

4 “As Free as I Am”: Retelling the Narrative

5 “The Other Side of Paradise”: Mythos and Memory in the Cemetery

6 “The Most Interesting Building in Georgia”: The Strange Career of Kitty’s Cottage

Part Three. Families Lost and Found

7 Enigmas of Kinship: Miss Kitty and Her Family

8 “Out of the Shadows”: The Andrew Family Slaves

9 Saying Something Now

Appendix 1. Guide to Persons Mentioned in the Text

Appendix 2. Timeline

Appendix 3. Kitty’s Possible Origins

Appendix 4. Kitty’s Children

Appendix 5. The Greenwood Slaves, Postemancipation

Notes

Bibliography

Index

![]()

Illustrations

FIGURES

1.1. Schneider on American kinship

1.2. The “white” myth

1.3. Kitty’s marriage to the “legally free” Nathan Shell as a relationship of law

7.1. Distribution of Nathan Boyd’s enslaved family

7.2. Nathan Boyd’s family

7.3. Family relations of Emma

7.4. Family of Russell Nathan Boyd

7.5. Family of Alford (Alfred) Boyd

8.1. The McFarlane slaves

8.2. Slave transfers in the Greenwood estate, 1805–55

8.3. Additional slave transfers by Ann Leonora Mounger Greenwood

8.4. Likely slave transfers by Bishop Andrew after the death of Ann Leonora Mounger Greenwood

PHOTOGRAPHS

Following page 180

Oxford cemetery. Bishop Andrew obelisk in foreground; Kitty memorial at base of water oak.

Kitty’s Cottage, ca. 1930

Kitty’s Cottage in Salem Campground, 1948

Kitty’s Cottage, 2010

Oxford African American community, early twentieth century

First Afrikan Presbyterian (Lithonia) performs Ancestral Walk and African Naming Ceremony, Kitty’s Cottage, June 19, 2008.

Cynthia and Darcel Caldwell, with Oxford Mayor Jerry Roseberry, Old Church, Oxford, Ga., February 6, 2011

Oxford College students and community members read names of enslaved Oxford residents, Old Church, Oxford, Ga., February 6, 2011.

Darcel and Cynthia Caldwell, with historical documents on the Miss Kitty story, February 3, 2011

Dr. Joe Pierce Jr. and Aaronetta Pierce next to Unraveling Miss Kitty’s Cloak

Detail from Lynn Marshall-Linnemeier’s Unraveling Miss Kitty’s Cloak

![]()

Preface and Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK SPANS history and ethnography, moving back and forth between the ethnographic present and multiple points in the past. Drawing on spoken recollections, published and unpublished documents, as well as architectural and landscape forms, I document the history of powerful myths about freedom and unfreedom. I simultaneously attempt to reconstruct historical happenings that these evocative, proliferating narratives may have obscured. As such, this study has been enabled and supported by a great range of communities, institutions, and persons, whom I can only begin to acknowledge or thank adequately.

The Emory University Center for Myth and Ritual in American Life (Alfred E. Sloan Foundation), the Emory Office of University-Community Partnership, and the Norman Fund of Brandeis University funded field and archival research for this project. Parts of chapter 5 were published, in a somewhat different form, as “The Other Side of Paradise: Glimpsing Slavery in the University’s Utopian Landscapes,” in Southern Spaces (May 2010). Parts of chapter 9 were published, in a somewhat different form, as “Saying Something Now: Documentary Work and the Voices of the Dead,” in Michigan Quarterly Review 44, no. 4 (Fall 2005). Permission to republish is gratefully acknowledged.

I remain deeply grateful to my students at Oxford College of Emory University during 1999–2001, and to our many community partners in Oxford and Covington, Georgia, including Allen Memorial United Methodist Church in Oxford, the historically African American congregations of Rust Chapel United Methodist Church and Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Oxford, and St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, Bethlehem Baptist Church, and Grace United Methodist Church in Covington. Our shared labor restoring and documenting the historic African American sections of the Oxford City Cemetery has been the enduring inspiration for this study. This work is also anchored in the deep wisdom and historical insights of Newton County’s African American community historians, including Mary Gaiter McKlurkin, Mildred Wright Joyner, Sarah Francis Hardeman, Sarah Francis Mitchell Wise, and Emogene Williams. In the local faith community, Rev. Avis Williams, Rev. Hezekiah Benton, Deacon Forrest and Sharon Sawyer, and Deacon Richard and Polly Johnson have been valued sources of support, historical knowledge, and encouragement. State Representative Tyrone Brooks has been a firm supporter of this work and a champion of social justice initiatives in the region. Virgil and Louise Eady shared remarkable family papers that cast the history of slavery in the community in new light. John Pliny “J. P.” Godfrey Jr. has been a tireless and intrepid partner in all these inquiries and allied activist adventures; I cannot imagine how this book could have been written without his insight, curiosity, optimism, and friendship.

In Dallas County, Alabama, I am grateful for the support and generosity of the Wayman Chapel AME church membership and to the many other residents of Summerfield, Valley Grande, and Selma who kindly gave of their time, family records, and knowledge. Alston and Ann Fitts, Brenda J. Smothers, and Sister Afriye Wekandodis have been invaluable and generous guides to Selma’s storied history. In Augusta, Georgia, I am grateful to Joyce Law, Travis Halloway, and the congregations of Springfield Baptist Church, St. John United Methodist Church, and Trinity Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, all of whom are linked to the story of Miss Kitty in different ways. In Iowa, Doris Secor generously welcomed us to Keosauqua and its Underground Railroad history; Lynn Walker Webster kindly guided me in uncovering Buckner-Boyd family history and the related history of the AME church in the state. In Rockford, Illinois, Rev. Virgil Woods, pastor of Allen Chapel AME Church, kindly guided me to the local descendants of Miss Kitty.

I wish to think the staff at many institutions, including Jane M. Aldrich at the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture (College of Charleston); Sharon Avery of the Iowa State Archives; the Georgia State Archives; the South Carolina Department of Archives and History; the Alabama Department of Archives of History; the Arkansas History Commission and State Archives; the Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL) of Emory University, especially Ginger Cain and Randall Burkett; Kitty McNeil and her staff at the Oxford College of Emory University library; Debra Madera at the Pitts Theology Library, Emory University; Probate and Superior Court staff in Newberry (South Carolina), Covington, (Georgia), Dallas County (Alabama), Augusta–Richmond County (Georgia), Morgan County (Georgia), and Greene County (Georgia); Nic Butler at the Charleston, South Carolina, public library; the public libraries in Newberry (South Carolina), Pine Bluff–Jefferson County (Alabama), Newton County (Georgia), Augusta–Richmond County (Georgia), Rockdale County (Georgia), and Greene County (Georgia), as well as the public libraries in Selma and Birmingham (Alabama); the South Carolina Library; the Washingtonia Division, Martin Luther King Jr. Library (Washington, D.C.); Washington Historical Society; Office of Public Archives and D.C. Archives (Washington, D.C.); the Manuscripts division of the Library of Congress; the National Archives and Records Administration, in their Washington, D.C., College Park, Atlanta–Morrow, Georgia, and Waltham, Massachusetts, facilities; the African American Museum of Iowa; and the library of the U.S. Department of State.

Among the many persons and organizations that have kindly assisted me, I should especially acknowledge the Moore’s Ford Memorial Committee, especially Rich and Janise Rusk, Waymund Mundy, and Robert Howard; the Newton County African American Historical Association, especially Forrest Sawyer Jr.; the Newton County Historical Society; the Oxford Historical Shrine Society, especially Jim Waterson, Marshall Elizer, Roger Gladden, and Valerie McKibben; Linda Derry of Old Cahawba (Selma, Alabama); and the Augusta Genealogical Society.

At Oxford College and the Druid Hills campus of Emory University, I am grateful to many supportive colleagues, especially Susan Ashmore, Leslie Harris, Francis Smith Foster, Thee Smith, Laurie Patton, Jonathan Prude, Robert Paul, Gary Hauk, and Joe Moon. Bradd Shore’s synthetic work on myth and ritual in American society, especially in Georgia’s Salem camp meeting, is a vital inspiration for this study. I am also deeply appreciative of the pioneering work on Newton County African American history by emeritus Oxford historian Ted Davis, on whose work I build. Over the years, I have greatly benefited from stimulating conversations about this project with Laurie Kain Hart, Rajeswari Mohan, Jean and John Comaroff, Natasha Barnes, Rick Parmentier, Evelyn Brooks Higgenbotham, Pete Richardson, James T. Campbell, and Alfred Brophy. Scott Schnell, Wyatt MacGaffey, Alan Cattier and Carole Meyers, and Allen and Cynthia Tullos all provided hospitality and intellectual inspiration during our journeys. Lynn Marshall-Linnemeier, Kevin Sipp, and Sister Afriye We-Kandodis have been invaluable interlocutors in reimagining aspects of Miss Kitty’s life and the lives of the other enslaved peoples explored in this book. Since 2004 the staff and participants in the Transforming Community Program at Emory University, coordinated by Leslie Harris, Catherine Manegold, Susan Ashmore, and Jody Usher, have been inspiring reminders of the possibilities for reconciliation as institutions grapple with the weight of a common, often painful history. I also wish to express my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for the University of Georgia Press for their insightful and generous readings, to my editor Derek Krissoff, to the superb copyeditor Bob Land, and to the whole team at the University of Georgia Press.

Since the summer of 2009 it has been a joy and privilege to come to know descendants of Catherine “Miss Kitty” and Nathan Boyd, now in their sixth generation. I have been deeply moved by their generosity and insights as we have together attempted to excavate this complex historical narrative. I am especially grateful to the late Mr. Lee Bradley Caldwell, the great-great-grandson of Miss Kitty, and his daughters Darcell Caldwell and Cynthia Caldwell.

My parents and stepparents, Ruth Auslander, Joe Auslander, Barbara Meeker, and the late Maury Shapiro, as well as my aunt and uncle Judy and Alan Saks, have been unflagging supporters of this project, proving constant encouragement as well as serene places to write. My sister Bonnie Auslander has been a deeply insightful reader and interlocutor, sensitive both to the overall structure of argument and literary inflections.

Above all, I am deeply grateful to my wife and colleague Ellen Schattschneider, who has shared every step of this project. She has driven us thousands of miles across the nation’s Southeast and Midwest, helped to scour archives, attended worship services and family reunions, and has critically engaged with every line in the manuscript. She has shared in my intellectual and emotional engagements with the memory of Miss Ki...