![]()

Flush Times and Fever Dreams

A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson

JOSHUA D. ROTHMAN

![]()

CONTENTS

Maps

PROLOGUE. The Cotton Frontier, United States of America

Part One. Self-Made Men and Confidence Men

CHAPTER ONE. Inventing Virgil Stewart

CHAPTER TWO. Inventing John Murrell

Part Two. Settlers and Insurrectionists

CHAPTER THREE. Exposing the Plot

CHAPTER FOUR. Hanging the Conspirators

Part Three. Speculators and Gamblers

CHAPTER FIVE. Purging a City

CHAPTER SIX. Defining a Citizen

Part Four. Slave Holders and Slave Stealers

CHAPTER SEVEN. Suborning Chaos

CHAPTER EIGHT. Imposing Order

EPILOGUE. Memory and Meaning

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

![]()

![]() Flush Times and Fever Dreams

Flush Times and Fever Dreams![]()

PROLOGUE

The Cotton Frontier, United States of America

As he rode from the Choctaw Cession in northern Mississippi toward the plantation districts of western Tennessee, Virgil Stewart likely pondered his future and its possibilities. Possessed of a discontented soul and a firm sense that he was fated for greatness, the twenty-four-year-old Stewart was an impatient and easily frustrated man for whom present circumstances never quite satisfied. His current situation was no exception. It was January 1834, and Stewart had managed to acquire a few small parcels of land and achieve a middling status that many would have considered impressive for someone from beginnings as modest as his. But mostly he peddled furnishings out of a trunk, and he dreamed of doing grander things with his life. His ambitions were no less fierce for their lack of focus, and like many young men of his generation he believed his destiny could be waiting over the next hill. So Virgil Stewart kept on riding.1

On arriving in Tennessee’s Madison County, Stewart paid a visit to John Henning, a minister and cotton planter with whom he had become acquainted several years earlier. As they talked, Henning mentioned that two of his slaves had recently vanished and that a local farmer and petty criminal named John Murrell had stolen them. Henning had no real evidence that Murrell was the thief. But he was certain, and he asked Stewart if he was willing and had the time to help him corroborate his suspicions. Rumor had it that Murrell would soon be taking a trip to the town of Randolph, and Henning said his son Richard intended to follow him. If all went according to plan, in the course of his travels Murrell would reveal the location of John Henning’s slaves, simultaneously exposing his perfidy and enabling the elder Henning to recover his property. Randolph, though, was on the Mississippi River, more than fifty miles from the Henning plantation. John Henning did not want his son to undertake such a long and potentially dangerous mission alone in the middle of winter, so he proposed to Stewart that he join the expedition. Saying yes changed Stewart’s life.2

Richard Henning never arrived where he and Stewart agreed to meet to begin their journey, so Stewart set off on his own. He located John Murrell, engaged him in conversation, accompanied him on his trip, and acquired information that he claimed confirmed Murrell’s theft of John Henning’s slaves. On returning to Madison County, Stewart reported his findings to Henning, who gathered a posse, went to Murrell’s house, and arrested him. Afterward, sitting in a tavern as Henning and other wealthy citizens showered him with accolades for his bravery and cleverness, Virgil Stewart felt like an important and respected man. His moment to emerge from the anonymous masses and lay claim to an extraordinary future had arrived. He could not have known that his attempt to capitalize on that moment would result in the deaths of dozens of people back in Mississippi, but had he known, he might not have cared. It would not be the first time he had tried to take a shortcut at someone else’s expense, and after all, every white man was entitled to make of himself what he could. This is a book about the thrill of that classically American promise and the furious, dark consequences of its pursuit.3

THE EARLY 1830S WERE stirring times for many Americans like Virgil Stewart, who lived in a country enjoying material prosperity and expansive growth the likes of which had not been seen since the years right after the end of the War of 1812. As technological advances, infrastructural improvements, and manufacturing innovations converged with the sale of large swaths of expropriated Indian land, a dramatically increased money supply, and government policies that enabled rapidly proliferating state and local banks to unleash a deluge of paper notes and liberal loans, Americans chased unprecedented opportunities in flourishing cities and on burgeoning frontiers. By the middle of the decade, the contours of the economic landscape in the United States were unmistakable. These were flush times, and the sense that nearly anyone might dip into a virtually limitless pool of money and acquire credit with few questions asked made for a heady atmosphere. Countless Americans dreamed that anything was possible for those willing to hustle.4

And hustle they did. Indeed, it was common wisdom among many observers that the United States had become a nation of strivers excitedly responsive to the demands and possibilities of market capitalism. Michel Chevalier, for instance, found an irrepressibly kinetic populace when he visited the United States between 1833 and 1835. An engineer on a mission for the French government, Chevalier marveled at the “passion for locomotion” he saw everywhere he went, and despite his ambivalence about Americans’ unending obsession with money, he had to concede that he found their “go ahead” attitude invigorating. “If movement and the quick succession of sensations and ideas constitute life,” Chevalier thought, “here one lives a hundred fold more than elsewhere.” Americans had no interest in idle chatter, no time to digest a meal, no ability even to sit still. Instead, all was “circulation, motion, and boiling agitation.” Every man had a scheme for realizing a fast fortune and the collateral conviction that a person of humble origins might soon be a giant among his fellows. Andrew Jackson himself best demonstrated that prospect, his storied rise from frontier wastrel to wealthy squire to the most forceful president the country had ever known having made him the paragon of the self-made man and among the most popular individuals of his age.5

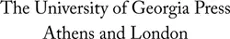

No part of the country was more flush in the flush times than what was then its southwestern frontier, because western Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and eastern Louisiana possessed some of the most fertile soil on the continent for growing cotton. With the demand for the crop from the domestic and British textile industries practically insatiable and average New Orleans prices for it increasing by 80 percent during the first half of the 1830s, the forced removal of tens of thousands of Native Americans from millions of acres of prime southwestern cotton land dovetailed with federal provisions that set initial prices of public land at just $1.25 an acre to create a frenzy of migration, investment, and agricultural production. Already vital to the American economy by the start of the 1830s, over the course of the decade cotton crops brought to market by southwestern growers swelled capital accumulation that accelerated national economic development, furthered the rising position of the United States as a global power, and cemented cotton’s place as the most significant commodity on earth.6

In 1831 the United States produced about 350 million pounds of cotton, just under half of the world’s raw cotton crop. The bulk of that crop was shipped abroad, and cotton exports in 1831, worth a shade over $25 million, accounted for 35 percent of the value of all the goods exported from the United States. By 1835 the cotton crop had increased to more than 500 million pounds, roughly 70 percent of it grown in Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and Louisiana. Cotton exports, now worth nearly $65 million, amounted to more than half the value of all goods America sent overseas, a majority cotton maintained every year until 1841 and for most years prior to the Civil War. Thanks almost entirely to southwestern cotton production, in 1834 New Orleans bypassed New York as the most important export city in the country, and it would hold that position for almost a decade. In 1839 the United States produced more than 800 million pounds of cotton. Its share of worldwide production had become nearly two-thirds, and 80 percent of American cotton came from the Southwest. Of the 86 percent of the crop shipped overseas, two-thirds of it went to England, which relied on the United States for 81 percent of the cotton its mills turned into yarn and cloth.7

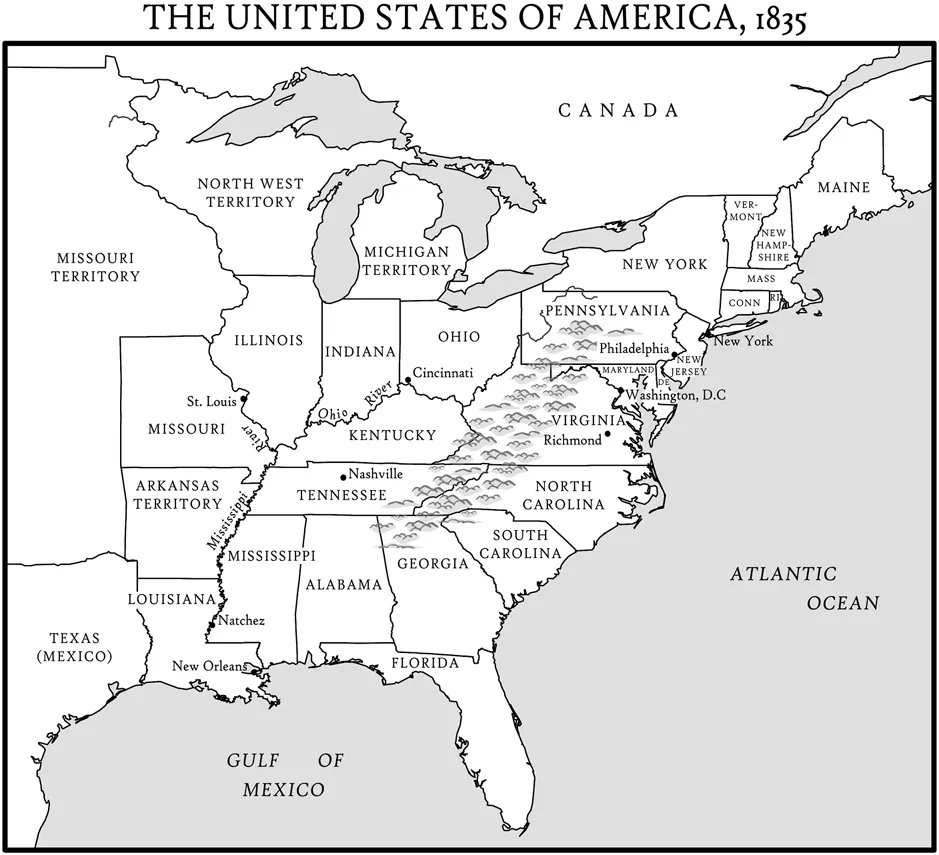

Little wonder, then, that when Virgil Stewart left his birthplace and sought opportunity in the 1830s, he headed for the Southwest, and even less that he ended up in Mississippi, which boomed like nowhere else in the region. The removal of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians between 1830 and 1832 opened the floodgates to white settlement of the northern half of the state, and hopeful purchasers swarmed federal land offices for months on end when they commenced business. The national government sold more than one million acres of public land in Mississippi in 1833 alone, twice as much as it sold in any other state. In 1835 the government sold nearly three million acres, which was more public land than had been sold in the entire country just a few years earlier.8

Capital came pouring into Mississippi as well. The number of banks incorporated in the state grew from one in 1829 to thirteen in 1837. Most had multiple branches, and their collective volume of loans bulged from just over one million dollars to more than fifteen million, seemingly with good reason. The nearly seventy-five thousand white people who moved to Mississippi between 1830 and 1836 doubled the state’s white population and provided an eager market for that money. Moreover, their ability to pay back what they borrowed appeared beyond question. In 1834 Mississippians produced 85 million pounds of cotton, a more than eightfold increase over the amount they had produced less than fifteen years earlier. In 1836 they brought more than 125 million pounds to market, and by 1839 the Mississippi cotton crop amounted to nearly 200 million pounds, at which point Mississippians grew almost a quarter of America’s cotton—more than the residents of any other state in the nation.9

Because cotton had the potential to yield returns very quickly and the efflorescence of banks made Mississippi a place where, as one man observed in 1836, “credit is plenty, and he who has no money can do as much business as he who has,” nearly anyone able to procure even a small piece of land could indulge the belief that he was on the road to success. It was no coincidence that the 1832 state constitution, which replaced the original 1817 charter crafted when Mississippi achieved statehood, was among the most democratic in the country. Mississippi’s growing population and its economic dynamism both reflected and reinforced broader cultural and political trends such that it epitomized the vaunted white male democracy of the age.10

Certainly, casual assessments of Mississippi’s circumstances made it hard to argue with the results. To Natchez lawyer William Henry Sparks, the 1830s were years when it was as if “a new El Dorado had been discovered; fortunes were made in a day … and unexampled prosperity seemed to cover the land as with a golden canopy[;] … where yesterday the wilderness darkened over the land with her wild forests, to-day the cotton plantation whitened the earth.” Author Joseph Holt Ingraham, who toured Mississippi in 1834, offered a similar observation, considering cotton growing a “mania” that would not pass “till every acre is purchased and cultivated” and the state became “one vast cotton field.” Ingraham concluded that “if the satirical ma...