![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE ANCIENT SOUTH

PHOTO, PAGES xx–1: Sunrise at Moundville. (Laura Shill, University Relations, The University of Alabama)

WHAT FOLLOWS IS a guide to the late prehistoric native peoples of the American South, particularly a group of societies known collectively to scholars as Mississippian chiefdoms. The concept “chiefdom” refers specifically and exclusively to societies characterized by the hereditary transfer of leadership positions and by a social system that included both elites and commoners but that had not reached the size or complexity of a state. The chiefdoms of the Ancient South were dubbed “Mississippian” because their way of life first developed in the wide Mississippi River Valley, where the largest Mississippian site was built at a place called Cahokia. These Mississippian chiefdoms did not conform to popular ideas about Native American life.

Mississippian societies were ruled by powerful leaders with the ability to raise armies of warriors from among their followers. They often lived in fortified towns, and they buried their chiefs and other important citizens in earthen mounds surrounded by riches acquired through pillage and long-distance trade. The Mississippians were quite interested in and knowledgeable about the movements of the stars and planets, and they built monuments that were also tools of astronomical observation. Using archaeological information and the accounts of sixteenth-century Spanish explorers, scholars have begun to understand something of the lives of these remarkable peoples.

Although most Americans have heard of Indian groups such as the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Creek, the societies depicted in this book have received almost no attention in the popular media, though to be fair, only in the last few decades have scholars come to understand something of this extinct social order. When the media do depict these societies, they tend to lump them unceremoniously with even earlier societies and refer to them all as “Mound Builders.” Many groups built earthen mounds throughout eastern North America during the last few thousand years; however, they can in no way be considered part of one mound-building culture. Piling up earth into symbolically potent creations was merely a widely shared trait.

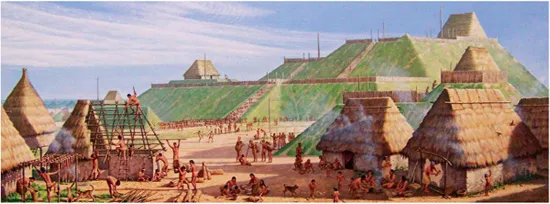

Daily activities depicted in a reconstruction of life in an elite neighborhood adjacent to Monks Mound and the Grand Plaza at Cahokia. (Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site)

The moundbuilders that we are interested in, the Mississippians, built their mounds for burial and as platforms for elite residences and temples. Their societies were found only in the South and only during the Mississippian Period, between approximately 900 and 1600. This time and place characterize what is referred to as the “Ancient South.” Charles Hudson developed the concept of the Ancient South as a complement to the “Old South,” a much more familiar idea referring to the era of slavery and cotton growing before the Civil War. In the minds of most Americans, including most southerners, this is the “ancient” history of the South. This guide shows, however, that the true beginning of the South as we understand it today began with the rise of the Mississippian chiefdoms.

The Mississippians were farmers, just like the Euro-Americans who eventually replaced them across much of the landscape. The same places in the region that were attractive to Mississippians were later attractive to the immigrating Europeans, and for the same reasons. As subsistence farmers, both groups sought the rich soil of the bottomlands in spots that received copious amounts of rain and little frost. Both groups dealt with many of the same problems of cultivation and came to interact with the land in similar ways. Like Mississippian peoples, the newcomers constructed their houses and outbuildings on the highest ground near the fields, sometimes on longabandoned Mississippian mounds, and founded many of their most important towns at old Indian sites.

The similarities extended to the kitchen as well. Mississippians and Euro-Americans grew many of the same foods and prepared them in much the same way. Women in Mississippian societies stewed vegetables until they were soft and limp and cooked nearly everything in animal fat, though they used bear fat instead of lard. By 1540, when southern Indians and members of the Hernando de Soto expedition sat down to eat the first recorded barbecue in the South, the technique had already been a tradition for many hundreds of years. And it is still in use today, of course, though in most cases beef, chicken, and pork have replaced deer, bear, and turkey.

In other words, the heritage of the Ancient South is in many ways the heritage of all southerners. Therefore, the responsibility rests on all of us to understand something of it and to enjoy and protect the remains of those once-great southern societies to which we owe so many of the region’s long traditions. An exploration of the Ancient South naturally begins with an examination of the origins of Mississippian societies.

The Mississippian Transformation

During the ninth and tenth centuries, the majority of peoples in what would eventually become known as the American South adopted a new way of life. This way differed from the old in many respects, but two were particularly important: the adoption of corn as the staple of the diet, and the development of politically and militarily formidable chiefdoms. Scholars once believed the new way of life spread from the Mississippi Valley as a result of an expanding and conquering population, but it has since been shown that in most cases the transformation was due to more indirect forces. Mississippian practices were adopted because they were perceived to be a successful way of organizing society and because it took a chiefdom to compete with another chiefdom. That is to say, chiefdom organization spread not only because it represented successful technologies and political principles but also because nonchiefdoms were vulnerable to the military might of their newly organized Mississippian neighbors and had to adapt or else lose their independence.

Southerners had grown corn in small amounts since about 200. It entered the region from one of three places: eastern Mexico, South America’s Caribbean coast, or the American Southwest — probably the last. Dozens of generations passed before a variety that did well in the climate of the South was bred, but that development may have triggered the rapid and widespread intensification of corn horticulture after 900. Corn was more productive and easier to store than the native plants on which southerners had previously relied. But corn also made more demands on its cultivators than the native plants, demands that altered their lifestyles. In a sense, with the adoption of corn as the major crop, southerners went from being gardeners to being farmers. In addition, nascent chiefs used the ability to store corn for long periods to their political advantage.

Before the Mississippian transformation, societies in the region were relatively small, and leaders arose haphazardly whenever an individual could accumulate enough influence, wealth, and charisma to command the loyalty of followers. But one’s position disappeared at death; it was not passed on to offspring. Mississippian chiefdoms, by contrast, were the first societies in southern history to include an elite segment characterized by the hereditary transfer of power. Although precisely how this elite segment of society developed is impossible to discover, it can be traced in part to the chief’s ability to reduce risk. Once corn began to provide the lion’s share of a population’s caloric intake, that population became more vulnerable to the effects of crop failure, which the chief mitigated by collecting part of every harvest to hold in public trust. In addition, chiefs seem to have legitimized the permanent hierarchy of the new political order by expanding their ritual actions and connecting them with the perpetuation of the sacred order of the universe. People began to see the chief as a representative of their principal deity, symbolized by the sun. Thus Mississippian societies merged the functions of religion and government.

Another important difference between chiefdoms and earlier southern societies had to do with warfare. Because of their relatively large populations and the presence of storable food, Mississippian societies could sustain substantial military forces. Nonchiefdom societies lacked not only numbers and sufficient stored food but also leaders with the power to command the military allegiance of their people. Chiefdoms were thus much more capable and efficient in military operations than the societies that preceded them. Although armed conflict was a regular part of Mississippian life, chiefs seem to have risen to power in part because they were able to narrow the scope of violent conflict. That is, chiefdoms were larger societies spatially and numerically than those that had preceded them, and because chiefs demanded cooperation within the chiefdom and unity against outside enemies, they were able to create wider areas of peace than those that had characterized pre-Mississippian life.

In exchange for participation in these chiefdoms, the common people received several benefits. By giving part of their harvest to the chief, they “bought” insurance against future crop failures. In exchange for occasional military service and communal labor, commoners were assured of peace with their neighbors and help against foreign enemies. Finally, by giving fealty to a representative of their god, they received spiritual gains in this world and the next. That said, costs and benefits were not shared equally between the chiefly elite and the commoners. Before the workings of chiefdoms can be explored in detail, however, we must examine the region in which these societies developed.

The Climate and Environment of the Ancient South

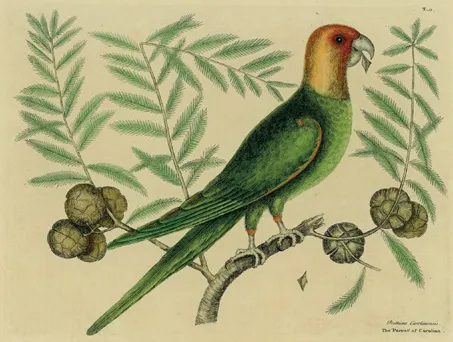

The landscape of the Ancient South differed in many important ways from that of the current South. Much of the Ancient South was covered in vast forests, and a significant percentage of those forests were old growth. Old-growth trees were huge, with lots of space between them, and because their limbs and leaves formed a canopy that kept out much of the sunlight, there was little undergrowth, making travel much easier than is possible in today’s dense, second-growth southern forests. The rivers of the Ancient South were not dammed and ran much cleaner and clearer than they do today. The flora and fauna have changed greatly as well. Many plant species we associate with the South had not yet been brought to the region, including peaches, kudzu, bluegrass, and peanuts, and the same can be said for animal species such as cows, pigs, horses, and chickens. On the other hand, several animals common in the Ancient South are now extinct or nearly so, such as passenger pigeons, Carolina parakeets, ivory-billed woodpeckers, and red wolves. Some plant species have also been lost, including the American chestnut, once the most common tree in the southern Appalachians. In other cases, native plants have had their ranges much reduced through competition with foreign species; for instance, English privet has taken over many of the areas where river cane once thrived.

In addition, the physical boundaries of the Ancient South differed from those of the modern South. Because of climatic differences, the South was larger than it is today. Specifically, between about 900 and 1300 the world experienced what has come to be known as the Medieval Warm Period, a stretch of particularly good weather during which the population of Europe grew, the Norse began to colonize the extreme north, and many of the great European cathedrals were built. In the Ancient South, the climatic episode coincided with the development and maximum growth of Mississippian societies. During that four-hundred-year period, the region extended as far west as eastern Oklahoma and as far north as the American Bottom around modern St. Louis. There were even short-term Mississippian settlements in northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

The Medieval Warm Period was followed by a climatic episode known as the Little Ice Age, which lasted from approximately 1300 to 1850. The Little Ice Age consisted of a series of unpredictable stretches of cold years interspersed with more moderate weather. In Europe during this time, the Norse colonies were abandoned, there was much famine brought on by crop failure, and several episodes of bubonic plague. In the Ancient South, the boundaries of the Mississippian world contracted until they closely resembled those of the South today. Many of the largest Mississippian centers were deserted, and although some were later reoccupied, others were abandoned forever, including the sites in the American Bottom and those farther north. Although climate alone was not responsible for this, the effect of climate on chiefdom societies was considerable. Mississippian farmers needed at least two hundred days without frost and at least forty-eight inches of rain each year in order to grow the crops necessary to sustain their societies.

The Parrot of Carolina, by Mark Catesby. Flocks of raucous and vividly colored Carolina parakeets were common in the Ancient South. (Mark Catesby, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, 1731–43)

The Largest White-bill Woodpecker and the Willow Oak, by Mark Catesby. Because of its club-like bill, the ivory-billed woodpecker was a potent symbol of war in the Ancient South. (Mark Catesby, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, 1731–43)

Not all places within the Ancient South were valued equally by the Natives of the time. The Mississippi Valley is where the Mississippian way of life developed, though it first emerged in what we would today consider the Midwest, around St. Louis. It is difficult to overstate the size of a river that drains approximately 1.25 million square miles and counts among its tributaries such major rivers as the Ohio, Missouri, Arkansas, and Red. The Mississippians viewed the river as a great serpent undulating across the land. For an idea of what the Mississippi River was like in its natural form, before the modern levee system was installed, we have to turn to such authors as Mark Twain in Life on the Mississippi (1883) and Thomas Nuttall in A Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory (1821).

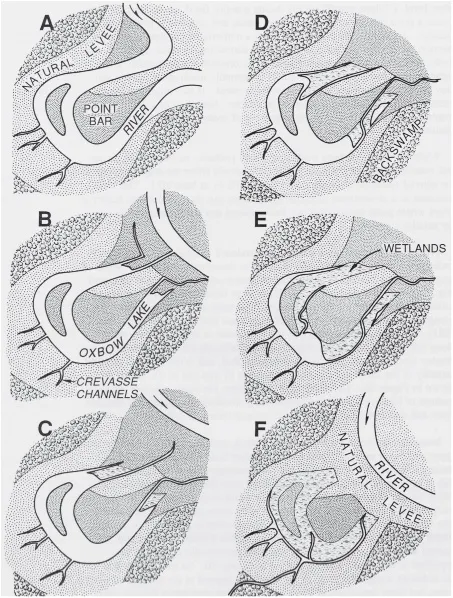

The vast floodplain of the Mississippi was covered with old-growth southern floodplain forest dominated by bald cypress, tupelo, sweet gum, and several varieties of submergible oaks. Mississippian peoples lived on the highest land available, the natural levees, but regular flooding would have been a fact of life. The Mississippi system is essentially a tremendous meander belt (a snaking, twisting watercourse) through a shallow valley marked by soft soils. As the river passes along its S-shaped path through the floodplain, water flows fastest along the outside edge of the bends, which results in soil being removed from those banks. The slower water on the inside of the bends cannot keep the soil particles suspended, so they are deposited on the inside bends. The S-shaped curve eventually becomes so pronounced that it takes on the appearance of a horseshoe. At that point, even a small flood can result in the horseshoe curve being cut off from the main channel if the river “jumps” over the small neck of land between the ends of the horseshoe, shortening the river and turning the S-shaped curve into a lake known as an oxbow.

The shores of oxbow lakes were among the best places to live for Mississippian farmers. The levee soils between oxbows and the main river channel were the richest soils for corn horticulture in the entire Ancient South. The lakes were full of turtles and many slow-water fish species, such as buffalo fish, gar, and catfish, that commonly weighed as much as eighty to one hundred pounds. Fast-water species, including freshwater eels, lived in the many tributaries. Countless migratory birds used the Mississippi Valley as a flyway, so during certain seasons the oxbow lakes teemed with several species of geese and ducks. A number of valuable plant species grew throughout the valley, perhaps none more important than river cane, which was abundant along the Mississippi and other waterways throughout the Ancient South. River cane was used for scores of purposes by Native peoples. (See the box feature River Cane, page 9.)

Formation of an oxbow lake. The adjacent levee soils and abundant resources made these lakes attractive places for Mississippians to settle. (Mississippi River Commission)