- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

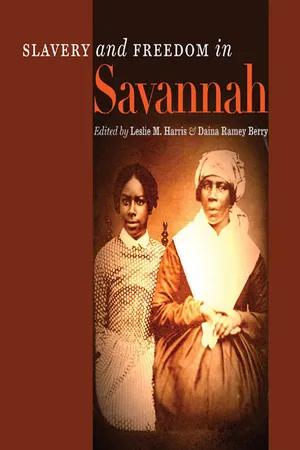

Slavery and Freedom in Savannah

About this book

Slavery and Freedom in Savannah is a richly illustrated, accessibly written book modeled on the very successful Slavery in New York, a volume Leslie M. Harris coedited with Ira Berlin. Here Harris and Daina Ramey Berry have collected a variety of perspectives on slavery, emancipation, and black life in Savannah from the city's founding to the early twentieth century. Written by leading historians of Savannah, Georgia, and the South, the volume includes a mix of longer thematic essays and shorter sidebars focusing on individual people, events, and places.

The story of slavery in Savannah may seem to be an outlier, given how strongly most people associate slavery with rural plantations. But as Harris, Berry, and the other contributors point out, urban slavery was instrumental to the slave-based economy of North America. Ports like Savannah served as both an entry point for slaves and as a point of departure for goods produced by slave labor in the hinterlands. Moreover, Savannah's connection to slavery was not simply abstract. The system of slavery as experienced by African Americans and enforced by whites influenced the very shape of the city, including the building of its infrastructure, the legal system created to support it, and the economic life of the city and its rural surroundings. Slavery and Freedom in Savannah restores the urban African American population and the urban context of slavery, Civil War, and emancipation to its rightful place, and it deepens our understanding of the economic, social, and political fabric of the U.S. South.

This project is made possible by a grant from the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services. This volume is published in cooperation with Savannah's Telfair Museum and draws upon its expertise and collections, including Telfair's Owens-Thomas House. As part of their ongoing efforts to document the lives and labors of the African Americans—enslaved and free—who built and worked at the house, this volume also explores the Owens, Thomas, and Telfair families and the ways in which their ownership of slaves was foundational to their wealth and worldview.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

The Transatlantic Slave Trade Comes to Georgia

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Sidebars

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Transatlantic Slave Trade Comes to Georgia

- Chapter 2 “The King of England’s Soldiers”: Armed Blacks in Savannah and Its Hinterlands during the Revolutionary War Era, 1778–1787

- Chapter 3 At the Intersection of Cotton and Commerce: Antebellum Savannah and Its Slaves

- Chapter 4 To “Venerate the Spot” of “Airy Visions”: Slavery and the Romantic Conception of Place in Mary Telfair’s Savannah

- Chapter 5 Slave Life in Savannah: Geographies of Autonomy and Control

- Chapter 6 Free Black Life in Savannah

- Chapter 7 Wartime Workers, Moneymakers: Black Labor in Civil War–Era Savannah

- Chapter 8 “We Defy You!”: Politics and Violence in Reconstruction Savannah

- Chapter 9 “The Fighting Has Not Been in Vain”: African American Intellectuals in Jim Crow Savannah

- Notes

- Further Reading

- Contributors

- Index