![]()

CHAPTER 1

Early European Views of African Bodies

Beauty

STEPHANIE M. H. CAMP

Though she was black, that was amply recompenc’d by the Softness of her Skin, the beautiful Proportion and exact Symmetry of each Part of her Body, and the natural, pleasant and inartificial Method of her Behaviours.

—WILLIAM SMITH, A New Voyage in Guinea (1744)

Early modern European travelers in Africa did not consistently generalize about a place called Africa and people called Africans. Neither the place nor the people existed for Europeans prior to the Atlantic slave trade and, especially, European colonialism in Africa in the nineteenth century. Within African imaginations, too, “Africa” came into existence through the slave trade and colonization. Previously, people of the sub-Saharan continent identified as members of kinship, political, and linguistic groups. European travelers to West and Central Africa helped to invent “Africa” (and African Americans) when they purchased people who had been severed from the family relationships and the linguistic and political affiliations that gave them identities as persons. In place of these former selves, slave traders imposed a new identity: enslaved “African” chattel. In time, the identity “slave” would define African Americans just as “African” would define the people of the subcontinent.

But in Africa during the 1600s and 1700s, these identities were very much still in the process of becoming. English involvement in the slave trade produced paradoxical experiences. On the one hand, it gave the mariners, merchants, and sailors who worked in the trade every possible reason to malign the people they bought and sold. And so they did—prolifically. At the same time, the trade gave some Englishmen (and other European men) the opportunity to spend time, sometimes years, in Africa. During that time, they had experiences that challenged what they thought they knew about gender norms, about women, and about Africa. European writers recorded their conflicts over sexual practices in particular, offering evidence of some of the ways that West African definitions of what made bodies beautiful differed significantly from European ideals, as well as from what Europeans knew of Africans. Many Europeans recoiled from these challenges to their worldview, but others, after an initial shock of disgust, found it difficult to sustain their repugnance over time. They came to see African bodies as diverse: black and tawny, female and male, slave and free, rich and poor.

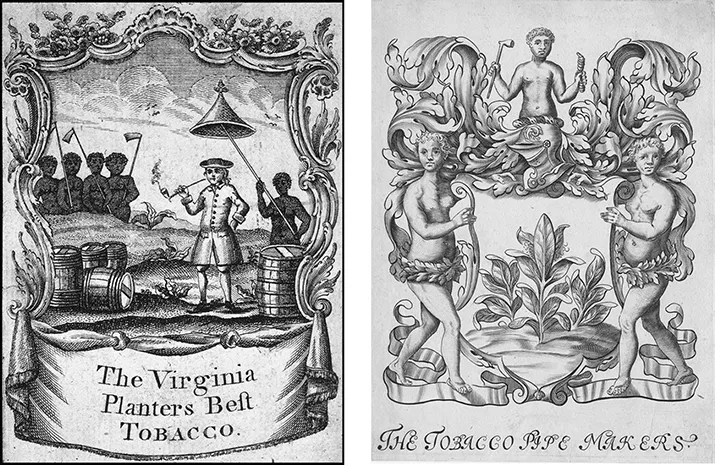

“The Virginia Planters Best Tobacco” and “The Tobacco Pipe Makers” advertisements depict partially naked female slaves.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase.

When the traveler Richard Jobson traveled along the Gambia River on “Guinea Company” (the slave trading Royal African Company) business in the 1620s, he met people he called Fulbie (Fulbe). Quickly interpreting them through their bodies, Jobson was pleased to note that they “goe clothed.” He then scoped out the differences between men and women and tried to figure out who, if anyone, was beautiful. Jobson approvingly noted that the Fulbe were “Tawny,” not “blacke,” and “handsome.” The women more so than the men: Fulbe women were “streight, upright, and excellently” well formed. They were blessed with “good features, with a long blacke haire, much more loose then the blacke women have.” They tended to their hair fastidiously, just as they did to their clothes and their dairy work. Being quite “neate and cleane” in their habits, should they be caught in any “nastinesse,” Fulbe women, like good English women at home, blushed with embarrassment. They worked, like Irish women, with cattle, but were much tidier than Irish women. Theirs was a “cleanlinesse [with which] your Irish women hath no acquaintance.” Jobson linked “Tawny” skin, “long [. . .], long” hair and straight bodies with “handsome” women, and he made a point of distinguishing the lighter-colored Fulbe from “blacke women” in general as well as from the “perfectly blacke, both men and women” Mandinka. In Jobson’s view, Africans came in multiple colors: tawny, black, and “perfectly black.” Not only were Africans not all one people, they were not yet all black. And, in Jobson’s estimation, the lighter brown skin of some Africans enhanced their beauty.1 Eur-africans and brown-skinned Africans received much praise for being beautiful.

But dark brown and black Africans were far from unrecognized by European men for their beauty. For instance, during his time in the Cape Verde Islands in the late 1640s, Richard Ligon met the most beautiful woman he had ever seen. She was “a Negro,” the mistress of a Portuguese settler and a woman “of the greatest beauty and majesty that ever I saw.” In his account, Ligon dreamily detailed her body’s exquisite form (“her stature [was] large, and excellently shap’d, well favour’d, full ey’d, and admirably grac’d”), the cloth and color of her clothing (she wore a head wrap of “green Taffety, strip’d with white and Philiamort,” a “Peticoat of Orange Tawny and Sky color; not done with Strait striped, but wav’d; and upon that a mantle of purple silk”), her jewelry, her boots. And her eyes! A decade had passed since his voyage, but Ligon had never forgotten their exotic allure. “Her eyes were her richest Jewels, for they were the largest, and most oriental that I have ever seen.” Her smile was a paragon—and not, Ligon insisted, simply because all Africans had white teeth. That misconception was a “Common error.” But hers were indeed “exactly white, and clean.” Ligon’s “black Swan” spoke “graceful[ly],” her voice “unit[ing] and confirm[ing] a perfection in all the rest.” Hers was a “perfection” that exceeded the grace and nobility of British royalty. The woman was possessed of “far greater Majesty, and gracefulness, than I have seen [in] Queen Anne.” Ligon’s readers must have been quite surprised to read a favorable comparison between their queen and an African concubine.2 Then again, it was not exactly easy in the middle of the seventeenth century to know what to expect when it came to representations of Africa. It was an age of intense contradictions.

Later in his travels, Ligon surprised his sixty-plus-year-old self with the force of the admiration and desire he felt for some of the “many pretty young Negro Virgins” he met later on his voyage. There were two “Negro” women, in particular, who took Ligon’s breath away. The two women were “Sisters and Twins” and their “shapes,” “Parts,” “motions” and hair were “perfection” itself. Indeed, they were works of art. True, Ligon admitted, their shapes “would have puzzl’d Albert Durer,” the German Renaissance painter known for his mathematical approach to proportion. And Titian, the Italian painter revered for his soft, fleshy representations of the human form and harmonious use of color, would have been perplexed by their muscles and “Colouring.” Still, the women “were excellent,” possessed of a “beauty no Painter can express.” The twins were unlike North Africans, East Africans, or Gambians, “who are thick lipt, short nos’d and [who had] uncommonly low foreheads.” In what ways the twins were different from these others, Ligon did little to clarify; he did not describe their facial features, bodies, or skin color. He did, however, detail their hair and their “motion,” both of which he found irresistible. They wore their hair neither shorn nor cornrowed, but loose in what Ligon deemed “a due proportion of length.” Their “natural Curls [. . .] appear as Wyers [wires],” and the women bedecked their corkscrew curls with ribbons, beads, and flowers. The occasional braid twisted adorably onto their cheeks. Their motions? “The highest.” Grace in movement was “the highest part of beauty,” and the twins had mastered it. Ligon was surprised to find in Africa such living embodiments of “beauty,” “innocence,” and “grace.”3

The emerging stereotype about African women’s rugged reproductive capacity was not wholly devoid of admiration of African women’s stoicism and physical strength, especially when European men (inevitably) compared African women to European women. In light of what they thought they witnessed in (or read about) Africa, some male writers came to see European women as annoyingly weak. Pieter de Marees announced in 1602, for instance: “the women here are of a cruder nature and stronger posture than the Females in our lands in Europe.”4 In this double backhanded compliment, de Marees hitched together African and English women, loading both with the burden of embodying British civility and its constitutive opposite, African savagery.

Charles Wheeler, an English trader who lived in Guinea for a decade in the employ of the Royal African Company in the 1710s and 1720s, shared Marees’s perception of the ease with which African women produced children, as well as his regard for it. “One Happiness, which those of this Part of the World enjoy before those of Europe,” Wheeler told William Smith, who later wrote about his travels, “is their Labours. These are Times with them so easy, so kind, so natural and so good, that they have no Need of Midwives, Doctors, Nurses, &c. and I have known Women go to Bed over Night, bring forth a Child and be abroad the next Day by Noon.” Wheeler admiringly attributed the good times that African women enjoyed during pregnancy and childbirth to their “natural” state of being. Citing the “Black Lady” with whom he lived during his decade on the coast, he (and she) credited above all women’s “Chastity” during pregnancy and menstruation. “You White People,” Wheeler’s Black Lady told him, “do not observe this Rule, [and] there are among you, Lepers, Sickly, Diseased, Ricketty, Frantick, Enthusiastic, Paralytic, Apopletic, &c.” European clothing made matters worse. English women’s “Stays, and Multiplicity of Garments [. . . as well as] the Multitude of other Distempers and damnable Inconveniences, [which they] through Pride and Luxury, had brought upon themselves” produced the “hard Labours” they suffered so terribly loudly. In Wheeler’s and his lady’s interpretation, civility and its sartorial demands distorted women’s bodies and led to painful parturition. African women’s lighter, looser clothing, “so contriv’d as to confine no one Part of the Body,” rewarded them with easier pregnancies and more dignified birth experiences. The natural manner in which African women gave birth extended to the care of newborns—with beautifully healthful results. No special “Provision [. . .] of any Necessaries” were made for newborns, and “yet all its Limbs grow vigorous and proportionate.” William Smith had lifted this last sentence from Willem Bosman’s influential 1705 book, but with an important addition: Smith thought that it was the coddling of infants in Europe that “makes so many crooked People.” The “vigorous and proportionate” limbs of African infants were born of unconstrained, natural female bodies. African women’s natural state rewarded them with ease in childbirth and straight-limbed children. African women, from Bosman’s, Wheeler’s, and Smith’s points of view, were innocents unscarred by the curse of Eve.5

The same slave trade that pricked English interest in Africa and contempt for Africans also elicited its seeming opposite: a need to engage with Africans and to know something about them. In order to make their purchases, male travelers simultaneously recognized, fantasized, and reshaped local identities. They perceived, as we have seen, differences among Africans—differences of culture, of skill, and in their bodies. European travelers were not incapable of recognizing human beauty in Africa. Even slave traders were capable of recognizing it, but with a twist. Slave traders interpreted bodies through a merchant’s mindset: set to turn some African people into property, they perceived beauty with the slave market in mind. In the mid-seventeenth century, Richard Ligon knew that the buyers of slaves in Barbados saw Africans as more than simply monstrous or hardy. Barbadian planters chose slaves “as they do Horses in a Market; the strongest, youthfullest, and most beautiful yield the greatest prices.”

The naval doctor John Atkins agreed. “Slaves differ in their Goodness,” Atkins opined in 1735. Based on his travels in “Negro-land” (West Africa), he found “those from the Gold Coast are accounted best, being cleanest limbed, and more docible” (though he thought they were also “more prompt to Revenge, and murder”). Slave sellers in Africa and in the Americas embellished Africans’ bodies in order to make them appear healthier, stronger, more beautiful. The reality of starved, exhausted, and likely ill bodies had no place in the market. Sellers washed the stain of urine, feces, and blood from the slaves’ skin, shaved and deloused their hair, and rubbed them with “Negro Oyle” (palm oil) or lard to make their skin glisten and hide the effects of the captives’ traumatic forced migrations. Improving slaves’ appearance of vitality was an essential part of getting them sold “to Advantage.” Indeed, the historian of the slave trade Stephanie E. Smallwood has called the aesthetic preparation of the slaves’ bodies for sale the part that “would matter most in the captives’ upcoming performance” in the market.6 It was to no slave trader’s advantage to insist that Africans were a uniformly revolting people. The irony, of course, is that slavery’s logic of commodification evacuated beauty of the power it often held. Commodified and enslaved beauty was anything but powerful.

Some English travelers thought they discerned a difference between African women and men, a difference in the aesthetic value of their bodies. Of those who compared men and women, most insisted that the men were far better made, smoother, and above all more symmetrical than the women. With some exceptions, African women, who challenged European gender norms so profoundly, were viewed as more unevenly made than men were.7 Their physiques, it was frequently claimed, had been disfigured by field work, pregnancy, and breast-feeding. The traveler Francis Moore claimed that the women he saw during his travels along the River Gambia in the 1720s were asymmetrically made with “one Breast [. . .] generally larger than the other.” The surgeon John Atkins, who had denounced the women of “Negro-land” for their distended breasts, nonetheless admired the male bodies he encountered. The men were “well-limbed, clean Fellows, flattish nosed, [. . .] seldom distorted.” The women were simply “not nigh so well shaped as the Men.” “Childing, and their Breasts always pendulous, stretches them so unseemly a Length and Bigness,” he wrote, seemingly with nose wrinkled.8

Rich...