![]()

1

To the Reader, Sincerely

DAVID LAZAR

Non men che saver, dubbiar m’aggrada.

DANTE, INFERNO XI

For it is myself that I portray.

MONTAIGNE, “TO THE READER”

Come here often?

We’ve both been around the block a few times. In fact, I think I may have even seen you loitering in my back pages. I don’t hold it against you. It’s like the old joke: we’re both here, after all. My apologies if that sounds slightly salacious. But just as Montaigne wished he could appear naked, and worried that he’d be cast into the boudoir, it’s that desire to be raw and that need to cook, wanting to blurt out everything and wanting, too, to be discreet, that creates the maddeningly necessary friction for essays. It’s that thinking about what you think you thought. Raw rarely wins.

I want something from you and you want something from me, and I’m not trying to just be chivalrous when I say I know I owe you a good time, in the broadest sense. What I want from you is more complicated, reader. You’re mostly doing a great job of giving me what I need just by being you. I know that sounds hackneyed: “Just be yourself.” And of course, to a certain extent, you’re my invention, whether you like it or not, the monster to my Frankenstein—or “steen,” depending on my mood. Potato, potahto. But if we call the whole thing off, we must part. Keeping all of this in mind, I think it’s fair to say you can read me like a book. But even as I’m imagining you, you’re (with a little help) imagining me. Which is to say, dearie, old pal of mine, that the thing about whistling in the dark is, “You just put your lips together and blow.”

Reader, I divorced her. And she me. And perhaps I’m looking for a surrogate, a perfect other, perchance at least a friendly friend to while away the hours conversing with. After all, I spend so much time talking to myself, writing little concertos of prose in my head, that after a time, having spent too much time walking around the city and thinking in concentric loops, layering idea upon idea only to have them evaporate like the lightest of brain soufflés, it seems to make sense to write them down. I try to tell myself that the story I tell is real, but really, what would that really mean, other than that I really mean what I say? Nevertheless, I think, I’ve always thought, that intention counts for something. Isn’t that recherché? Wasn’t intention nine-tenths of the law in some places?

I’m sincere, in other words. Whether or not I’m honest is a judgment that shouldn’t be self-administered. I’m sincerely sincere. I’ve always loved the song in Bye Bye Birdie, “Honestly Sincere”:

If what you feel is true

Really feel it you

Make them feel it too

Write this down now

You gotta be sincere

Honestly sincere

Man, you gotta be sincere

If I didn’t have a dash of modesty, I’d be entirely and wholly sincere! I’m even sincere about the things I say that are slightly less than sincere, but which I try to sincerely slap myself around a bit for having been insincere about. It’s one of the ways I can show you that I’m being reasonably honest. It’s also a sincere display of how flawed I am. Look, if I told you I was thirty-nine, and then told you I was fifty (don’t roll your eyes), you’d think I was a bit of an idiot, but at least you’d know I had a self-correcting mechanism. But I’d take everything I say with a grain of salt if I were you. And I mean that sincerely. I’m fifty-six, by the way. You could look it up.

If I really just wanted you to like me, I’d tell you a story. It would be a story of adversity of some kind, and I would be the protagonist. It would arc like crazy, like Laurence Sterne on Ritalin, and I’d learn something really valuable from my experience. But who knows where an essay is going to go? Really. I’d be a defective essayist if all I did was tell stories. Sincere stories. Like the one about walking out of my house yesterday. I was feeling my age as summer bled into fall on a day that was really too nice for such a metaphor. A guy who was working on installing a new wrought iron fence outside (I love wrought iron—partly because I love the way it looks, and partly because of “wrought”) told me he liked my style. “Thanks!” I said, thinking I was so smart to have bought that ’50s vintage jacket online last week for fifteen dollars. Then the fine fellow said, “You look like Woody Allen.”

I was taken aback. I had never been told I looked like Woody Allen. I’m not sure I want to look like Woody Allen. I don’t mind sounding a bit like Woody Allen. It comes with the territory: Brooklyn Jewish, and he was an enormous influence on me. But, look? So I said, “I’m sorry, did you say I looked like Errol Flynn?” And he said, “Yeah, that’s right, but not from The Adventures of Robin Hood but from The Modern Adventures of Casanova, in 1952, when he was dissolute.”

I made that last part up. Forgive me? He really did say I looked like Woody Allen.

For the last few years everyone I’ve met has been telling me I look like Lou Reed. I don’t see it. I was in one of my favorite bars in Chicago, the Berghoff (essay product placement), and a man was staring at me. He finally made his way to my table and said, “Excuse me, I don’t mean to bother you, but are you Lou Reed?” I said, “No, I’m John Cale.” He said, “Who’s John Cale?” I mean, how can you possibly know who Lou Reed is without knowing who John Cale is? It’s like walking up to someone and saying, “Are you Oliver Hardy?” “No, I’m Stan Laurel.” “Who’s Stan Laurel?”

In any case, I wasn’t even sure of how I felt about that. Lou Reed was great looking, although a bit older than I; he was getting a bit weathered . . . and do I have to look like a Jewish New Yorker in the arts? What’s the connection between Woody Allen and Lou Reed? Who’s next? Mandy Patinkin? Harvey Fierstein? Hey, what about Adam Brody?

Look, reader, I’m sincerely not trying to look for things to complain about, but part of bedecking myself is the confusion and profusion of identities “I” shuffles through. Surely you have some version of this? Don’t you have some walk-in closet of self or selves? I do have some version of a Fierstein shirt, a Patinkin suit, I suppose, especially when I’m being shticky. When my persona is shticky. When it’s less so, I like to think I’m closer to

Me and my shadow

Strolling down the avenue

Oh, me and my shadow

Knock on the door is anybody there

Just me and my shadow

You might call me a self-made man. Hello to the essay Lazar, goodbye to the talker-walker Lazar. The former has inscribed the latter, imbibed the latter, put him through a meat grinder, and feasted. I’m self-immolated, a phoenix. Rise, he said. Or: Monty Python: I write rings around myself, logically, if not impetuously. (Don’t you wish John Cleese had written essays?) The spirit of Whitman is in the essay: we enlarge ourselves even as we’re talking about our pettiness, our drawers, our moths, our doors. The “I” that takes us along (remember that terrible song “Take Me Along”?—bad songs stay as long as delightful ones) does so because we’re attracted to the way it vibrates or concentrates, clicks or skiffles. The essay voice is a boat that can carry two.

And no voices are alike—my own jumpy, interruptive style, which might not be to everyone’s taste, will be seen as a flaw or a defect by some, and by others as the only dress in my closet. But let me tell you that I think that I, like most essayists, want to be known. That this “created” voice you’re hearing (created voice, creative writing, creature of the night!), this persona, this act of self-homage and self-revelation, occasionally revulsion, frequently inquisition or even interdiction, actually is tied very closely to the author. Since I’m frequently my subject, to say the “I” who is writing isn’t quite me is slightly fatuous; which “I” is the more sincere, the more honest self? That one? The ontology of essay writing involves a conversation with oneself, and one, after a while, exchanges parts back and forth so that writer and subject become bound, bidden, not interchangeable but certainly changeable. I become what I’ve created, and want to be known as that.

For Montaigne the wanting to be known was partly due to the loss of his soulmate, Étienne de La Boétie. At one point Montaigne offers to deliver his essays in person. I like that idea, reader. We’ve lost the telegram, after all. Wouldn’t you like to open the door and have Mary Cappello or Lia Purpura hand you a personalized essay? “Essay, Ma’am,” might just enter the lexicon. I’d write you one. I could come over and read this one to you, if you like. Like Montaigne, I think I’m in search of company, and I talk to myself in essays as a way of finding it. So you’re really very close to me. A matchbook length, a cough, a double-take away.

At the end of his invocation “To the Reader,” his introduction to his Essais, in 1580, Montaigne bids farewell. It’s a double joke. He’s saying goodbye because, in an extension of the modesty topos, he has urged the reader to not read his vain book of the self, his new form: the essay. He is also bidding adieu to the pre-essayed Montaigne, the one who isn’t self-created, self-speculated, strewn into words and reassembled, if so. A playful gauntlet. And he is invoking the spirit of his death. To write oneself is to write oneself right out of the world. It’s the autothanatological moment: “when they have lost me, as soon they must, they may here find some traces of my quality and humor.”

Montaigne says his goal is “domestic and private,” and so it may have been, at first, though Montaigne’s literary ambitions start seeming more and more clear as the essays lengthen and grow more complex, as Montaigne takes more risks with what he offers of himself. And my own, I ask myself, in the spirit of Montaigne. What are they? I’d say they’re twofold: (1) to write the sentence whose echo doesn’t come back; (2) to be known, in some essential way, without sucking the air out of the mysterium.

Montaigne’s address to the reader occurred when doing so was still a relatively new, a reasonably young rhetorical move. According to Eric Auerbach, Dante seems to have been the first writer to establish an intimately direct poetic address to the reader. Dante then plays with this form, using it a structuring device, tossing off asides. And Montaigne quotes Dante in the essays. This dynamism is epistolary, liberating and seductive. Sotto voce. Let me whisper in your ear. It’s just the two of us. Come on, you can tell me. Or rather, it’s okay, I can tell you. The confession. After all, I’m writing about myself, and my subject is really important, right?

Except: Reader, she says—grabbing me by the shoulders, telling me that what she needs to tell me is more important than anything that’s ever been told—I married him. And you thought comedies ended in marriage? In my triad of great addresses to the reader (meaning me, in the place where you are now), Charlotte Brontë’s direct address will always be for me the most stunning, the single most relational moment, perhaps, in literature. “Reader.” And for the moment it’s your name. Call me Reader. And as a male reader, and as a male adolescent reader, my response was always: You should have waited for me.

Addresses to the reader are not, you see, just about intimacy. They’re also secretly about infidelity.

Reader, comrade, essay-seeking fool, blunderer upon anthologies for whom the book tolls, when I said, “I divorced her,” I’m sorry for the lack of context, but really what I wanted to talk about here wasn’t her and me, that was a bit of a feint, but you and me. You know I’ve been missing you. Since we last met, across a crowded essay, I’ve really been thinking about nothing but you. Well, you and me, and me and you. Let’s go for a little walk, shall we? Flaneur and flaneuse, or flaneur and flaneur. I might even let you get in a word or two.

Baudelaire must have breathed Montaigne. And his “Au Lecteur” or “To the Reader” (also the title of Montaigne’s invocation) is almost like Montaigne inverted, Montaigne through the looking glass. Actually, Baudelaire and Charles Dodgson were contemporaries, which makes a kind of perverse sense. If you look at some of the language, some of the phrasing of “Au Lecteur,” you find a Montaignean sensibility, if not a Montaignean tone: “In repugnant things we discover charms”; “our souls have not enough boldness”; “Our sins are obstinate, our repentance is faint.” But whereas Montaigne is only suggesting, via a modesty trope, that his readers may be wasting their time (not really), Baudelaire is saying (Hey, you!) we’re going to hell in a panier à main, which means, ironically, that we need to listen to his brotherly jeremiad. “Hypocrite reader, my brother, my double”—the antithesis and the brother (and sister) of Montaigne’s and Brontë’s addresses. Theirs are seductive in their close (reading), one-on-one asides to us, just us. They need an intimate, we feel, and so appeal to our need for intimacy. We need what they need. But so does Baudelaire, because who else would dare say that to us? Hey—you! Yeah, I’m talking to you! I remember being shocked by that, the audacity, someone daring to say that to me. He would have to . . . know me pretty well. My brother, my double? Push, pull.

Depending on my mood, I could tell you that there are better things to do than reading essays—going for a walk, watching a movie, throwing a rubber ball against a stoop. But at other times, perhaps when I’m treading across Charles Lamb’s “A Bachelor’s Complaint of the Behavior of Married People” or Eliza Haywood’s The Female Spectator, Nancy Mairs’s “On Not Liking Sex” or John Earle’s Microcosmographie, I feel like telling you that there may not be anything better to do, that in fact you’re wasting your time reading novels, or going to plays, looking at art (I can’t ever speak against the movies—I just can’t), or doing the things you do to keep yourself alive. You should just read essays and live on the delight. The delight of Stevenson, Beerbohm, M. F. K. Fisher. But modesty tropes are worthwhile, so part of me wants to tell you: Go for a walk.

So, reader. Reader. Darling reader. There’s something I want to tell you. It’s a story, but it’s more than a story. It’s what I think about what’s happened to me. To us. And where I might be headed. We might be headed. It involves movies, books, walking around if it’s not miserably cold, and your occasional willingness to laugh at my jokes. Together, we might be able to cobble together an essay. We can assay! I’d love it if you really thought you knew me.

CODA

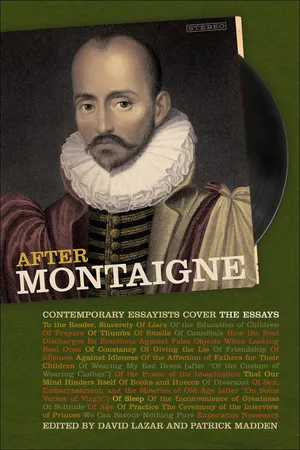

Montaigne’s “To the Reader,” less than a page, contains much of the internal friction and frisson of the creation of the essay’s persona. It’s full of play and a theoretical masterpiece in miniature. “To the Reader” has been my inspiration, and has inspired and intrigued essayists for 435 years. So I wanted to join Montaigne’s along with a couple of my other favorite readerly salutations and try to let them breathe in my own question mark as lasso out to whoever might find or be looking to find that note of connection in the voice of reader and writer, writer and reader, who in the essay play a game, at times, of musical chairs.

![]()

2

Of Liars

E. J. LEVY

Lying is indeed an accursed vice.

MONTAIGNE, “OF LIARS”...