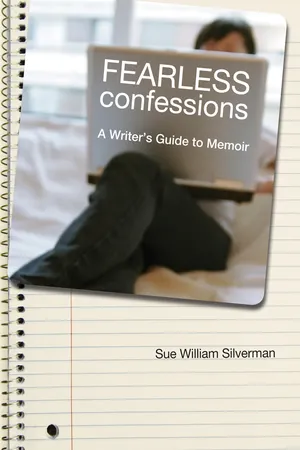

![]() Fearless Confessions

Fearless Confessions![]()

Chapter One

The Longest Paragraph

You should write your own story,” Randy, my therapist, says to me.

I’ve been in therapy about a year. I slouch on the blue couch in Randy’s Atlanta office, lean my head back, and stare at the ceiling, nervous to meet his gaze. I put my feet, in red leather Reeboks, on his coffee table. This table, this couch, his office — they’re all designed to comfort his clients.

But I don’t feel comfortable. I want to say to him: Write about myself? You’re the one who must be crazy! Why would I want to write about myself? I want to say to him: I don’t have anything to say about myself. Nothing. I don’t have any earthly idea how to write about myself … I mean, even if I wanted to!

I want to say: No, no, no!

“Well?” he says, waiting.

I glance at him, at his blue eyes — blue — the peaceful color of the couch, of the walls of his office. But as he raises his eyebrows, inquiring, I look away again.

The plant in the corner by the window seems dry, brittle. I want to tell him to water it. Maybe we can spend the session discussing horticulture. I lean forward and retie my left sneaker, even though the knot is perfect. I want to do anything but respond to what surely must be, if not a crazy idea, then clearly an impossible one.

“I don’t have anything to say about myself,” I answer.

“You sound angry,” he says. “Why don’t you want to write about yourself?”

He knows I’ve been trying to write novels for years. So what he really means is: Why don’t I stop writing fiction and write a true story?

A true story.

On this day in his office, I’m sure that the official word, memoir, isn’t in my mind. How could it be? Back then, in the early 1990s, I hardly even knew the title of one.

I want to say: None of my writing teachers ever suggested I write about myself. So why would you? I want to say: Who’d even want to read a story about me?

A story about me.

He means: Why don’t I write a story about a woman whose father, when she was growing up, sexually molested her? He means: Why don’t I commit to paper secrets I’ve hidden for years, secrets about both my childhood and my current disarray—that I’m in therapy for sexual addiction and anorexia?

Which means, in my mind, that I’d be writing a story about a woman whose life is embarrassing, humiliating, shameful.

Why would I want to do that?

It’s true that last week I did write about myself — but only as a therapeutic exercise, and only for Randy to read. I wrote a short, unmailed letter to my father about growing up as his daughter, living in houses that felt like prisons.

That letter I wrote is now in Randy’s hand.

“That’s all I have to say about myself.” I nod toward the letter.

“I know you think that,” he says. “But I don’t think that’s true.”

Periodically, over the next few years, Randy continues to say, “Write about yourself.” I always respond, “I have nothing to say about myself. Nothing at all.”

Now, today, for the first time, he includes a new word, the word safe, in his statement. He says that maybe now I’ll feel safe enough to write about myself because just last week both my parents died: my mother from lung cancer, my father from a stroke. I am relieved they are dead. I am sad they are dead. I am angry they are dead, angry because they died without once, even on their deathbeds, acknowledging the incest. They never apologized. Nothing. I also feel stunned to realize that, within six days, I have suddenly become an orphan.

Yet I’ve always felt like an orphan, anyway, haven’t I?

Randy would probably say that if I wrote my story, I’d find out why I always felt like an orphan; I’d also better understand the relief, the sadness, the anger.

I stare at an Ansel Adams photograph hanging on the wall across from me. I see it. I don’t see it. Images, snapshots of my childhood seem, for a moment, more real, as if I’m watching a slideshow or leafing through pages of a photograph album.

No one would want to see these photographs—photos of me and my father — would they?

I’ve told Randy facts and feelings about my childhood. I’ve cried. I’ve raged. I’ve also sat in his office silent. Speechless.

But I’ve never described these snapshots in my head, these images. I’ve never talked about sensory details, what it sounded like, looked like, to be me, growing up. Maybe it is a narrative comprised of this imagery that must be written.

A book to help me understand my childhood … and a book, Randy frequently says, to help other women as well.

But a book sounds too daunting. Maybe something shorter. An essay?

Finally, after years of Randy’s urging, I whisper, “Okay, maybe I’ll write a paragraph about myself. But that’s all I have to say.”

A short paragraph, I want to add, but don’t. A very short paragraph. Three sentences. Four at the most. A paragraph just to humor Randy. A short paragraph so he’ll stop bugging me. A very short paragraph so he’ll see that he’s wrong. So he’ll understand, once and for all, I have nothing to say.

But even if I did, hypothetically, have something to say about myself, who’d want to read it? Maybe there aren’t any other women like me. No one would be interested in my messy life — that story.

No one, except Randy and my husband, even knows my secret.

On that particular day, driving home to Rome, Georgia, from Atlanta, about an hour and a half away, I try to reassure myself: I’ve written hundreds and hundreds of pages of fiction. Surely I can coerce one small paragraph of nonfiction from myself just to show Randy I tried.

When I arrive home, I change into “professional” clothes to prepare for the evening class I teach at a community college. I wash my face. Apply makeup. All traces of the wrinkled cotton sweatpants and scuffed red Reeboks are removed. I fix my hair so none of my students will suspect that I’m in therapy, will suspect that, at times, I’m a physical and emotional wreck. Any visible residue of a chaotic childhood is rinsed away. I don a skirt, starched shirt, and blazer. To enter a classroom with thirty students, I must appear to be in perfect control, adult.

I sit at my desk while the students bend over their blue books, composing their final in-class essays before summer vacation. Outside the windows of this cinderblock structure, dusk shadows magnolias. A sheen of chartreuse pollen from loblolly pines dusts the windows. Even though it’s a beautiful evening, I prefer to be in here. I love being with my students — even knowing most of them would rather be outside.

Ironically, here, they are the ones who believe they have nothing to say, nothing to write. Most of them hate English class, hate to write. Nevertheless, week after week, I encourage them to place sentences on pieces of paper. “You can do it!”

I simplify the indecipherable rules in the Harbrace College Handbook into easy-to-follow instructions for them. “This is a comma splice. This is a run-on sentence.” Before they can pass English Composition 101, they must successfully complete an essay exam required by the Georgia Board of Regents. All semester I prepare them for it. I want them to do well. I glow when I’m able to convince even one student to not hate English.

I glow brighter when I’m able to convince even one student about the power of language. I felt breathless when Marci changed her major from dental hygiene to English, after an offhand comment I made one day when asked by a student why I liked to teach English.

“I guess because I love words,” I replied.

After class, Marci, a timid young woman, waited for the rest of the students to leave the room. Alone, she finally approached me. Quietly, she said, “I didn’t know you could love words. I love words, too, but I’ve never told anyone before.” She feared her friends and family would make fun of her. Here in rural north Georgia, she told me, education, reading, writing, weren’t valued. This was her secret.

“Oh, yes,” I say. “It’s fine to love words. And you’re a good writer. If you’d like to write extra essays, I’d love to read them.”

She turned in an extra essay about a place in the woods where she hid, where she read books, where no one would find her. No one had ever discovered her secret.

On that evening back then, I did not fully comprehend that what I wished for Marci was, in many ways, what Randy wished for me.

Now in the classroom, as my students write, I finish grading their essays from last week, and I read — oh, dear — many abstract thoughts, many wayward sentences. I read, “I loved my grandmother because she was kind and loving.” And I write in the margin that I want to know how she was kind and loving. “Give concrete examples,” I write. “What details and images show her kindness? Be specific.”

Many of these students are the first in their families to attend an institution of higher learning. Most are either older women or single mothers training to be nurses, dental assistants, something practical. They take this class because it’s required. But toward the end of the semester, even as some continue to write about their favorite pet or loving grandmother, others, tentatively, go deeper. One student explores how uncomfortable she feels when entering a store because, as an African American, she believes white shopkeepers watch her, certain she’ll shoplift. Another student describes a fishing expedition with her grandfather, urging the material into a more meaningful nature essay than I expected from such a familiar topic. Others write about abusive husbands or boyfriends. Alcoholic fathers. Secret abortions. In tiny letters at the bottom of their essays they write: “Please don’t let anyone see this.”

Of course I don’t.

In the margins of their papers, I praise their courage. And I wonder whether some students trust me with their words because — even as I try to hide all traces of my own past — they sense I haven’t always been this in control, this professional. Maybe this is why some share their tentative words, their secrets, with me.

After the semester ends, I’m alone in my house, my husband at work. Next to my computer is a stack of over three hundred pages of my most recent unfinished novel, a novel about child abuse (sort of). But the protagonist isn’t quite me; the story isn’t quite mine. I riffle the paper. All these chapters, all these pages, all these paragraphs, all these sentences, all these words … why do they not say what I want?

I must be stupid.

In fact, my own high school as well as my undergraduate educational background is extremely shoddy — another secret. Which must prove I’m stupid. A failure. I will never be a writer.

I am procrastinating.

I think about Marci, all my students this past semester brave enough to place secret words on pieces of paper, courageous enough to show them to me.

The cursor on my computer blinks.

I type the word “Preface.” I write a long paragraph about my father’s career, his numerous professional accomplishments. Before I realize it, I’m at the bottom of the page. I’ve already finished the one paragraph that I promised Randy!

Except I haven’t yet said anything about me. A memoir should probably be about me, right? So hurriedly, almost before I realize what I’m writing, my fingers type: “My father is also a child molester. I know, because he sexually molested me.”

Yes, this is the truth. This is what happened. I had a father. He had a successful career. But behind closed doors, when no one watched, when no one saw, he sexually molested me.

This is what happened to me.

Straight facts. Unadorned truth. I’m not a fictional character such as those in the novels I write.

“I was born on Southern Avenue in Washington, D.C., in a white, two-story duplex across from a cemetery, and in that house …”

I am writing the story of living in that house, writing about a little girl named “Sue.” A girl who is me.

I am on page ten or so before I realize: I don’t know how to write a memoir.

Up until then, I only wrote and read short stories and novels.

I print out the ten pages and read what I’ve written. Fact by fact, I’ve set down what it was like living in that white house on Southern Avenue. I’ve just completed a scene in which my father is teaching my mother to drive a car for the first time. There I am, a little girl, with my father, mother, and sister in our black Chevy, driving down quiet roads in northern Virginia.

But the inside of the car is not quiet — my angry father is yelling at my scared mother: “Turn the wheel left, shift into third gear, give the accelerator more gas.” And because of my father’s rage and my mother’s temerity, we slide onto the shoulder, roll down a short incline, and end up in someone’s front yard. The woman in the house rushes to our car, helps us out, helps me, gently checking for broken bones.

I wrote this scene. I set the facts down on paper. I reread it. And I think to myself: so what? We had a car accident, but who cares? Loads of families have accidents, many much worse than ours. No one, after all, is hurt. Why would anyone care?

There must be more to the story, more to the scene, than this. There must be a reason why I even recall it so vividly.

Then, as if I’m following a whisper—a whisper because I must listen closely, carefully—I write what I now know to be true. I write what I now, years later, understand to be the significance of this scene. Which isn’t only the car accident — that’s just a straight fact. More significant is this unknown woman who touches me with a hand that’s soft and caring. The strange woman gently touches me to determine if I’ve broken any bones.

Why is it important?

I hear this whisper as I write: Her tou...