![]()

CHAPTER ONE

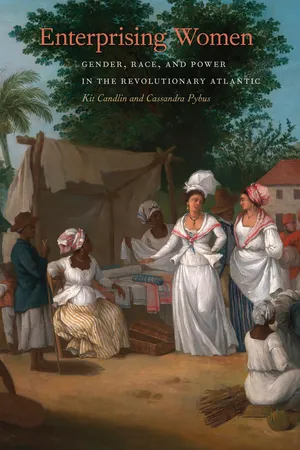

The Free Colored Moment

WAR AND REVOLUTION IN A BRAVE NEW WORLD

WHILE THE SEVEN YEARS’ WAR raged across the Atlantic world, a motley collection of British speculators, financiers, merchants, and other hopefuls bided their time. With the ink on the Treaty of Paris of 1763 barely dry, they fell over themselves to divide the spoils from defeated France. Bringing great fortunes and even greater credit to bear, they inundated the British government with proposals, suggestions, and advice in order to secure a share in the new prosperity.1 Provinces in India, the whole of explored Canada, the Floridas, and four brand-new colonies in the Caribbean: the Seven Years’ War had been good for Britain, and the metropolitan moneymen could barely contain themselves.

With the East India Company ruling its share of the subcontinent jealously, popular attention turned to Atlantic gains.2 Most eyes were on the Caribbean. In the age of King Sugar, it was an easy choice to make. Over the next fifty years slavery would loom even larger in the account books of empire, and slave-grown produce throughout the world would almost double, but the 1760s were the planters’ golden age and a nadir for humanity.3 Fine ladies took their well-dressed chattel for walks through fashionable London, and hardy sea captains in Liverpool and Lancaster counted out the body spaces on newly minted slave ships. If they thought about it at all, few could even conceive of a world without slaves or the things slaves labored to grow. And if anyone did stand up and say something, there were over fifty MPS in the British Parliament—the West India lobby—who would tell them to sit down again.4

By far, the most sought-after new land therefore was to be found in the windward Caribbean territories of Grenada, St. Vincent, Dominica, and Tobago, which became known as the ceded islands. The Lords Commissioners for New Lands was set up partly in response to the rush, while new governors in the region complained of the workload and the effort that went along with these new conquests. From his base on Grenada, Robert Melvill,5 the ceded islands’ first governor, went so far as to “ease the expense” of settling newcomers by using his own money, while his subordinates on lesser islands, like St. Vincent and Dominica, struggled to prevent the new arrivals from encroaching on Indian land. The collective history of these colonies forms the Caribbean backbone of our story of women.

The imperial gains of 1763 began the second phase of British expansion in the Caribbean, pushing the power base out from colonies like Jamaica, Antigua, Montserrat, Nevis, and St. Kitts in the north and Barbados in the south and filling much of the space in between. By the end of the eighteenth century, under external pressures from war, revolution, and migration, this second phase of Caribbean growth led to a third and final phase, when the frontier colonies of Trinidad and Demerara, at the very bottom of the archipelago, were conquered and occupied in the 1790s.6

For the most part, these ceded islands were comparatively undeveloped frontier spaces that had experienced isolation and a lack of investment prior to the British arrival.7 In contrast to the deteriorating soils and oversubscription of the older colonies, however, the opportunities they represented seemed boundless. Domestic British broadsheets and magazines—particularly in Scotland—were full of descriptions of the potential of this new territory. An article in Scots Magazine waxed lyrical about the “abundant fertility of the soils,” which, the magazine argued, would “raise genteel fortunes” for anyone who went there.8 In Ireland a young Edmund Burke was incredulous that anyone could disparage such a fruitful settlement, the glorious product of “English valour.”9

Unsurprisingly, after 1763, offers of land in the ceded islands were eagerly taken up. Concerned that just a few magnates would buy up too much land, a limit of three hundred acres for every application was imposed to help diversify the people who would come to the new territories.10 On Grenada, legislation was even proposed to financially assist poorer newcomers to partake in the Caribbean bounty.11 New planters were so rapacious on St. Vincent that within two years of formal British control, settlers acting without the sanction of the London government had forcibly seized three thousand acres of land previously designated as Indian space.12

Free people of color also found this region attractive, and they flocked to the Windward Islands from the 1760s onward. Relegated to the margins of white society, these people had a precarious existence in the older colonies. Tales of stolen free colored patrimony, of forced separation, and of capricious whites only too happy to let free people of color fall on hard times are staples of Atlantic world history.13 For stateless and vulnerable free colored people relocating from colonies such as French St. Domingue, Martinique, and St. Lucia, the southern Caribbean was compelling. Little is known about the communication channels between free colored populations, but it seems likely that people heard that the British imposed far less strict regimes in the fledgling colonies of the ceded islands than in their older possessions.14 Free colored people in the new colonies could buy land, often without caveat, and there were no restrictions on their movement, on whom they could marry, or on whether they could gather in numbers or carry weapons. In the years following the takeover, free colored men could even become officers in the militias of Tobago and Grenada—something the paranoid Assembly of French St. Domingue had found unthinkable.15

There were also comparatively large numbers of free colored people in these islands already. Many had been manumitted by their former owners or had been born from unions between isolated French or Spanish planters and their slaves in the early part of the century. These were habits that many British migrants readily adopted, and many slaves continued to be freed throughout the eighteenth century. The existence of societies of free colored people throughout the new British colonies made assimilation for others much easier. So great were the numbers that by 1783 free people of color on Grenada were 53 percent of the total free population. The majority of these free colored people were women.16

As the effusive writing in Scots Magazine suggested, many of the new arrivals from Britain came from Scotland, and they would play an important part in the story of free colored women. For years the Scots had played second fiddle to the English, and antipathy toward the Scots remained a virulent stream in English culture.17 Certainly there were large numbers of Scots on Jamaica, and Scottish firms had sewn up the trade of St. Kitts and Nevis, but many more Scots were poised to take advantage of the new conquests. With Lord Bute as the first Scottish prime minister of a unified Britain, the end of the Jacobite wars, and the highland clearances in full swing, there was little to stop many Scots from migrating to the Caribbean. In doing so, these opportunists easily turned the fortunes of the Seven Years’ War into what was undoubtedly the eighteenth century’s Scottish moment. Scots were appointed throughout the new dominions. Robert Melvill was the ceded islands’ first governor, Archibald Campbell became governor of Jamaica, James Grant became governor of East Florida, while George Johnstone was governor over the border in West Florida. James Murray was awarded Quebec, and just a few years later John Murray would become governor of New York. The imperial opportunities presented to Scots in the middle years of the century were exploited with enthusiasm.18

The Scots tended to form close-knit groups connected by marriage, birth, and kin. They operated in tight networks, they were notable for aggressive acquisition and savvy business sense, and, in an age of patronage, they promoted each other unreservedly. Competing with the English for the spoils of empire, they had to use clannishness as a way to survive.19 Robert Melvill was particularly ready to plant his compatriots in the councils and assemblies over which he held control. In Dominica, Tobago, and Grenada, Melvill made sure that new councils were stacked with Scots.20 These interloper appointees highlighted the fault lines in imperial rule by exacerbating the bitter disputes between the Crown and elected assemblies. In myriad ways political tensions riddled the southern Caribbean.21

The Scots knew how to play the game. Hand in glove with their hard business sense came a social permissiveness and a forward-looking, cando attitude. Coming from cosmopolitan and almost exclusively military backgrounds, many governors encouraged this approach.22 Melvill used his power to buy up, through proxies, not only the three hundred acres he was allotted on Grenada and St. Vincent, but a further thousand on Dominica. When questions were raised over this portfolio later in his life, he had a tract written that absolved him from any guilt since his purchases, it was argued, were made only as an enthusiastic “example” for his fellow planters.23 He was only one of many Scots to aggressively work the system in their favor.

Unlike the early settlers on Jamaica in the seventeenth century, there were no years of experimentation for those arriving on the ceded islands. Planters came with a fully developed sense of the planting system and its pitfalls. They knew which crops to grow, how to grow them, and in which soils they worked best. Most knew about hurricanes and the climate, and how best to mitigate their effects. Numerous popular books and almanacs were eagerly read, helping the colonists to learn about dangerous diseases and the ever-present threat of insects. Thanks largely to the existing colonies, the new men also knew how to manage and control their slave workforces.24

Using existing networks of Scots across the Atlantic world, new settlers arrived in the southern Caribbean with a colonial support structure in place. Merchants, factors, and agents—many of whom were closely tied by marriage or kinship—were only too ready to take a share of the enterprise. Friends in older partnerships, trusts, and corporations, who brought considerable prior experience and expertise to bear, often formed new merchant companies and partnerships. Mcdowell and Millikin, Bartlett and Campbell, and Telford, Norton and Co. were just three of the many successful Scottish firms that were created out of older combinations. This activity was coupled to substantial home-based industries, such as the law, dominated by families like the Baillies, the Houstons, and the Campbells. From Aberdeen to London, the ports of greater Britain could all be harnessed by Scottish firms and utilized for everything from merchant marine enterprises to shipbuilding, from storage to distribution.25

Born of conquest, the new colonies formed the last Caribbean frontier, a deep space filled with competing loyalties and mixed populations. Without clear borders and between empires, these colonies were sites of contestation where more often than not colonial governors had to negotiate their authority against a backdrop of threats and unrest. Even when war did not threaten, planter assemblies would regularly fall into disputes between the nominated representative of the Crown and their own sectional interests. Landowners argued incessantly in a constant stream of property claims and counterclaims.26 Looming over these internal disputes was the threat of slave revolt—especially as the number of slaves brought into these colonies completely dwarfed those arriving in the older possessions. Pressures were compounded—especially on St. Vincent and Dominica—by a series of debilitating wars with black Caribs.27 With resident French Catholic populations in all of these new islands, and well-populated French dominions like Guadeloupe and Martinique just a short sail away, British governors also found themselves embroiled in bitter contests over religion and custom.28

Despite the insecurity and the administrative problems, these colonies were overwhelmingly places of fortune and possibility. These themes, which marked the region in the last decades of the eighteenth century, created a unique atmosphere where sustained social control was difficult to achieve for distracted governors, and where populations were mixed to a level that seriously undermined the smooth running of the colonies. In this space of compromise and accommodation, a comparatively level and highly permissive culture arose. Taking advantage of this permissiveness were free people of color, some of whom began to inherit from their European fathers or partners.29 As they grew in wealth, free colored people also grew in stature, and as the century progressed whites found that they no longer enjoyed an exclusive hold on land tenure, slave ownership, and influence.

This was a fluid, frontier world, however, where new British conquests sat uneasily beside the other great empires in the region. More than once would these islands change hands as wars, revolutions, and revolts tore across the Atlantic world. The American Revolution, followed closely by the French Revolution, triggered a series of lesser but no less disruptive colonial revolutions fought largely around the Caribbean Sea. The French retook Grenada, St. Vincent, and Tobago during the American War of Independence, along with the Dutch colony of Demerara, accelerating the animosity between the earlier French inhabitants and newer arrivals from Britain. But with the British destruction of the French fleet in the Caribbean in the closing stages of the American Revolutionary War and with mounting financial difficulties at home, France was forced to return these colonies in the peace of 1783.30 Every time a colony changed hands like this, a new group of people would be unsettled by the conflict. This transience made the southern Caribbean—with the close interconnectedness of its islands—an ethnic polyglot, very different from the homogeneity of the older European possessions.

Despite all the drawbacks, the southern Caribbean in the eighteenth century continued to be a place for new men and women, be they Scots migrants or free people of color. Here, on the edges of America, such people could exploit the gaps in the imperial framework and draw on a strong community of support. By the 1...