![]()

PART ONE

The Ancestral House

We’re the first potential parents who can contain the ancestral house.

—Wilson Harris, The Whole Armour

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Down to the Mire

Travels, Shouts, and Saraka in Atlantic Praise-Housings

African Guardian of Souls,

Drunk with rum,

Feasting on a strange cassava,

Yielding to new words and a weak palabra Of a white-faced sardonic god—

Grins, cries Amen,

Shouts hosanna.

—Jean Toomer, “Conversion,” Cane (1923)

Jesus been down

down to de mire

Sister Josie, you must come

down to de mire

—“Down to de Mire,” Slave Songs of the

Georgia Sea Islands (1940)

From W. E. B. Du Bois to Jean Toomer, several key early authors of African American modernity turned southward to Gullah/Geechee terrain—the Altamaha, the Georgia rice fields, the shout-driven rhythms of the Charleston—to dip their art into living waters of a folk authority more complex and transfiguring than they could know. Their texts bear poignant, often opaque witness. As Toomer’s Cane, for example, depicts a Georgia folk culture in urban migration and modernizing transition, it also registers a conservative remnant, the “African Guardian of Souls” who, though “converted,” remains present as another kind of converting force working from within a counterculture of modernity. Toomer’s “Conversion” reveals that whatever else Afro-Atlantic Protestant conversion has been, it has emerged from a creolizing double agency wherein the Soul Guardian says Amen, shouts liminal grooves that congregate workings of old African genius.1

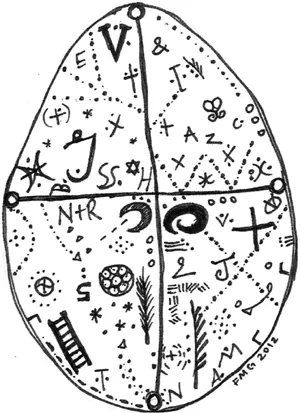

Along Cane’s swamp trails, African goat paths, and Dixie Pikes, we enter a limbo gateway between Africa and the Americas. This “limbo imagination of the folk”—with Toomer’s Guardian of Souls—passed supply through “the gateway complex between cultures” conceptualized by Wilson Harris, and herein readers too are called ever-lower into saltmarsh and mire, to identify “with the submerged authority of dispossessed peoples.”2 Going down to the mire entails a journey into deaths and birth-crampings of global modernity. In the lowcountry of coastal Carolina, Georgia, northeast Florida—and its routings into/from a wider Atlantic world—Afro-creole praise societies used ring shouts like “Down to the Mire” to construct limbo gateways of conversion, testing flexibility, restoring suppleness, undoing and redoing the calling-responsive boundaries of individual members, to build structures of corporate and even judicial agency.

Language also emerges converted and converting from this gateway. Especially at the creole contact zone—the most charged site of the African linguistic substrate’s submerged authority—the word bears stunningly limber witness. How can we know this “mire” down to which the seeker may be called? Is it the “area of wet, soggy, and muddy ground” of Webster’s New College Dictionary?3 If it is the “myuh” recorded by WPA interviewers from Georgia ring shouters descended from African Muslims, might it be the Pulaar maayo (or “river”) recalled by the Muslim headman Salih Bilali to the Georgia “master” who held legally defining title to him? Or the “ ‘Mighty Myo,’ which figures as a river of death” in a “sorrow song” noted by Du Bois?4 Might this ring-shouted “myuh” also have ties to the emergence of Jamaican myal, which Edward Long first described in 1789 as a recent establishment, “a myal dance … a kind of society” that renders its initiates “invulnerable” to whites through its spirit-guarding ring dance performed—as a missionary wrote from Jamaica in the 1840s—mostly by women, backed by the ritual circle’s humming and timekeeping: “by hands and feet and the swaying of their bodies”?5 How comprehend the word given so much linguistic and performative supplement? This gateway of limbo performance calls for respectful apprenticeship (sacrificial expenditures of ego), as we see in Lydia Parrish’s description from Georgia: “Of all the ring-shouts I know, ‘Down to de Mire’ is in more ways than one the most interesting. In the center of the ring, one member gets down on his knees and, with head touching the floor, rotates with the group as it moves around the circle. The different shouters, as they pass, push the head ‘down to the mire.’ ”6 Here, the “mire” or “myuh” signifies in performed, embodied relation to restored black Atlantic behaviors. But what are the convergent memories that find restoration in this myuh/maayo/myal/mire? Christian and Islamic prayer? The “I bow my head to the ground” of the moforibale and moyuba (Yoruba ritual greetings or prayer) in which “[o]ne head honors another by going to the floor”?7 When we encounter a word, say “death” or “god,” we must ask how it travels and has reached across the gulfs of various contact zones. We should reconsider, in this context, the Latin religare (“to bind back,” “retie,” “bond”) basing our “religion,” and its closest Yoruba equivalent: the awo (“secret” or “initiate knowledge”) embedded in divinations of the babalawo (guardian-father of secrets).8 We may recognize that Toomer’s African Guardian of Souls, in saying “Amen” to religion while also channeling nations of guarded knowledge, asserts a reciprocal model of agency that challenges Americans’ genealogical assumptions.9

More than any Anglo–North American contact zone, the Sea Islands of Carolina, Georgia, and northeast Florida have served as sacred groves of the African Guardian of Souls’ submerged authority. From lowcountry landings, commercial lines of triangulation connected the Sea Islands to the British Isles, Africa, and the West Indies. We may first notice lines running from Barbados to Charleston along routes of “the odyssey” of Barbadian settlement of Carolina—founded as the colony of a Caribbean colony.10 In the wake of the American Revolution we may chart routes from Charleston, Savannah, and St. Augustine ports, moving Loyalists and enslaved or allied Africans and creoles to the Bahamas, Jamaica, and throughout the Atlantic world.11 The War of 1812 left more crosshatching on our nautical maps, moving free black refugees from coastal plantations to repatriation in Trinidad.12 These flows of people, goods, ideas, and language shaped complex anglo-creole assemblages in interface with other Atlantic assemblages. Along with Deleuze and Guattari, we find “[c]ollective assemblages of enunciation” moving in rhizomatic patterns, “agglomerating very diverse acts, not only linguistic, but also perceptive, mimetic, gestural, and cognitive” in “a throng of dialects, patois, slangs, and specialized languages.”13 The lowcountry’s creole language (Gullah or Geechee) offers vital perspective on complex machineries of globalization and countercultural feedback.

The salt marsh is rhizome. Amid tidal flows over oysterbeds and mudflats, groves of arborescence (live oak hammocks) rise over sediment-trapping baffles of sweetgrass and spartina that extend precarious terrain. Resurrection fern and Spanish moss cover gigantic limbs of the oaks prized for use in the curved ribs of sailing ships. The lowcountry is a gateway of terrestrial, riverine, and marine flows. Any effort to territorialize this space within a strictly national narrative can account for only part of the Sea Islands’ cultural history. Indeed, the creole cultures around Charleston, Savannah, and Jacksonville test the waters separating the plantation South from the West Indies, and the Americas from Africa. Here we may find rites of psychic and social reassembly that work points of maximal Afro-creole authority to form a deep nexus of Afro-Atlantic Protestantism. It is an orphaned authority, however, long seen as “mumbo jumbo” or as a pinch of marketable local flavor thickening a vacation economy’s okra soup. Its temporal-spatial perspectives of relation are rapidly being vacated as gated “plantation” communities reterritorialize Geechee space and insert themselves over marsh grasses’ old baffles and expensively “renourished” beaches. The hold of Gullah/Geechee communities upon ancestral land and ties to transgenerational embodied knowledge—what French historian Pierre Nora terms “environments of memory”—has grown so tenuous that Congress passed the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Act in 2006, allocating $15 million over ten years to establish the “Gullah/Geechee Heritage Corridor” for the “preservation and interpretation of the Gullah/Geechee cultural heritage.”14

The notion that Afro-creole rites and environments of memory might offer epistemological value is new to most people of Western education and upwardly mobile aspiration, be they white or “of color.” Could the enslaved really have fashioned, in their hodgepodge “mumbo jumbo,” model reassemblies of cross-cultural desire and authority? The Presbyterian slaveholder, Rev. Charles Colcock Jones of Liberty County, Georgia, voiced his frustration over the slaves’ unwillingness to stick to the script of their standard hymnals: “The public worship of God should be conducted with reverence and stillness on the part of the congregation; nor should the minister … encourage … responses or noises, or outcries of any kind during the progress of divine worship; nor boisterous singing immediately at its close,” adding that “[o]ne great advantage in teaching them good psalms and hymns is that they are thereby induced to lay aside the extravagant and nonsensical chants, and catches and hallelujah songs of their own composing and when they sing … they will have something profitable to sing.”15 Similarly, one Methodist contributor to the Southern Christian Advocate in 1846 complained of the “deplorable exhibition of pseudo religion” in Gullah praise societies and of the “remarkable tenacity” of “ancient superstitions, handed down by tradition and propagated by so called leaders.” He asserts that “[i]nstead of giving up their visionary religionism, embracing the simple truth … our missionaries find them endeavoring to incorporate their superstitious rites with a purer system of instruction, producing thereby a hybrid, crude, and undefinable medley of truth and falsehood.”16 Such hybrid medleys seem to have traveled well.

The 1843 complaints of the English Baptist missionary James Phillippo in Jamaica point to a regional black Atlantic religious movement: “[A]t the conclusion of the war with America, some who had been imported from that continent, mysteriously blending together important truths and extravagant puerilities, assumed the office of teachers and preachers, disseminating far and wide their pernicious follies.”17 Likewise, the Bahama Argus printed an editorial in 1831 arguing against official sanction of black Baptist preachers who had established island congregations following the (mostly Gullah) Loyalist migration of 1783–84: “[A]lthough temporary fear of censure may induce a degree of demure decorum among them, yet there would be a proportionate want of real reverence for what they deem a ‘John Canoe’ exhibition … more in conformity with the noisy rites of Bacchus, than with the sober doctrines of the Christian faith.”18 While Rev. Phillippo, Rev. Jones, the Bahama Argus, and the Southern Christian Advocate sought to block the flows and production of black sacral desire and authority—and organize them along lines of plantation profitability—African guardians of soul performance were not easily stilled. A certain carnivalesque “noise” unsettled white missionaries. But their real fear was of countercultural black authority in congregation: an orphaned agency of gulfs that may still baffle the “purer system” of instruction to which we are all variously subject.

As Sea Island and West Indian cultures developed in interface, Afro-Christian praise societies channeled conversions of ancestral spirits and Holy Spirit in three key ways: (1) via initiatory patterns of seeking and narrating authoritative vision in spiritual “travels”; (2) via polyrhythmic ring shouts that sustained linkages of body, mind, and spirit; and (3) via sacrificial economies of remembering the dead and feeding the children. This chapter essays an archaeology of rites by which lowcountry praise societies spread Afro-Atlantic Baptist congregations to places as far-flung as the Bahamas, Trinidad, Jamaica, Nova Scotia, and Sierra Leone.19 We will examine how these praise-housings have fed contemporary literary stepchildren. Calls issued in 1993 by Cornel West for a “politics of conversion” and Paul Gilroy for a “politics of transfiguration” had indeed already been sounded in a literature by (or of) women seeking to conserve and remodel (post)plantation praise-house assemblies.20 These Geechee-infused novel travel-tracts (Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, Toni Cade Bambara’s The Salt Eaters, Paule Marshall’s Praise-song for the Widow, Gloria Naylor’s Mama Day, Erna Brodber’s Myal, Earl Lovelace’s The Wine of Astonishment, and Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, to name a remarkable artistic congregation assembled in a fifteen-year period between 1977 and 1992) have contested the white-supremacist, patriarchal filiations of the church. These works often take shape as conversion “tracks” under the spiritual parentage of a powerful female “pointer.” They foster alternative spaces of sanctuary and bear witness to a cosmopolitan conservatism emergent from forced navigation in a globalizing world.

“You Compel to See That Baby”—A Heterodox Conservatism in the House

With independent African Baptist congregations formed in Savannah and Augusta by 1777, Georgia became a gateway from which black missionary agency spread throughout the U.S. South and the anglo-Caribbean.21 Mechal Sobel has described the attractions of the Baptist faith for enslaved Africans, the compatibility of Baptist rites and worldview with African practices, Baptist grounding in ecstatic regeneration of the spirit, and the appeal of congregational independence.22 While the highly visible ministries of George Liele, David George, and Andrew Bryan were spreading black Baptist institutional agency in Georgia, the predominantly Africa-born plantation communities of coastal Georgia, which had experienced a surge of slave population—increasing from about 420 in 1751 to 16,000 in 1773 after massive importations—were bringing conversions to bear on Christianity.23 Although documentary evidence for the emergence of antebellum bush arbor and praise-house societies is sparse, colonial Christian activity, coupled with the prestige of Savannah’s independent Afro-Baptist ministries, appears to have been strong enough that Protestantism became the dominant element of black religion in Georgia between 1775 and 1815, and Georgia émigrés proved seminal in transporting their Baptist faith across an Afro-Atlantic world.24 By making use of a variety of older sources—augmented by interviews with ex-slaves collected by the Georgia Writers’ Project (1940), Lydia Parrish (1942), and Lorenzo Turner (1949)—and comparing this material with practices presumably carried to the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Trinidad by Georgians between 1783 and 1816, we may chart assemblage-structures by which Geechee praise societies helped to initiate a creolizing Baptist faith in the Caribbean.

Margaret Creel has described how Gullah praise societies served as the social, spiritual, and judicial force of the enslaved, building such community alignment that “reportedly there were no orphans on the Sea Islands.”25 Entry into Gullah societies found initiatory culmination in a period of spiritual travel known as seeking or mourning. This journey “in the wilderness” began with the seeker being apprenticed to a spiritual parent who monitored the seeker’s travels (dreams, visions, prayer)...