![]()

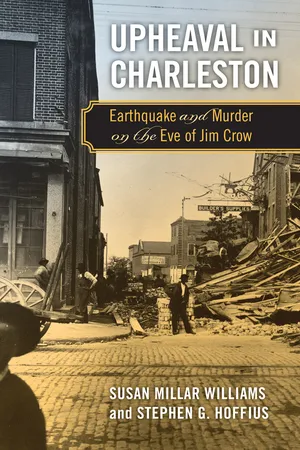

UPHEAVAL in Charleston

EARTHQUAKE AND MURDER ON THE EVE OF JIM CROW

Susan Millar Williams

Stephen G. Hoffius

![]()

Contents

PREFACE. Living with Disaster

ONE. The Great Shock

TWO. Seeds of Destruction

THREE. “The Earthquake Is upon Us!”

FOUR. A World Turned Upside Down

FIVE. The Earthquake Hunters

SIX. Aftershocks

SEVEN. An Angry God

EIGHT. Labor Day

NINE. “Bury the Dead and Feed the Living”

TEN. The Comforts of Science

ELEVEN. Relief

TWELVE. Waiting for the Apocalypse

THIRTEEN. Rising from the Ruins

FOURTEEN. The Old Joy of Combat

FIFTEEN. Wrapped in the Stars and Stripes

SIXTEEN. Fault Lines

SEVENTEEN. Standing over a Volcano

EIGHTEEN. Killing Captain Dawson

NINETEEN. The Trial

EPILOGUE. Rebuilding the Walls

Acknowledgments

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

![]()

Preface

LIVING WITH DISASTER

Susan Millar Williams

CHARLESTON HAS ALWAYS stood on shaky ground. Vulnerable to the fury of nature and the brutality of man, the old port city has served as the stage for the major acts of the great American drama. It landed more enslaved Africans than any city in the original thirteen colonies, reaped a vast fortune from their labor, surrendered to the British during the Revolution, led the charge for secession, and fired the first shots of the Civil War. When that war was lost, the city was occupied by federal troops and bound by U.S. laws that turned the state’s racial hierarchy on its head.

By the early 1880s catastrophe had become a way of life. Wars, hurricanes, fires, floods, epidemics, and riots had come and gone. Most black Charlestonians had endured the galling yoke of slavery, as had their parents and their parents’ parents. Most white men over the age of forty had fought and bled in the Civil War. The city was burdened with more than its share of widows and orphans. The citizens of Charleston, white and black, thought of themselves as survivors.

On August 31, 1886, the city was struck by a new and unforeseen calamity: the most powerful earthquake ever recorded on the east coast of North America. Buildings collapsed, dams broke, railroad tracks buckled and derailed trains. Fissures split the ground and water spouted two stories high. Miraculously, fewer than one hundred people died, though many more were injured.

The terror of the experience stayed with people all their lives.

I FIRST STARTED thinking about the earthquake in 1988, when one of my students at the College of Charleston wrote a research paper about it. She simply intended to find out what had happened—what fell down, who was injured, how people coped. Instead, she uncovered conflicts that surprised us both. Why were whites so angry when black people prayed and held religious services in the public encampments? Why would a white Episcopal minister threaten to beat a black woman with his walking stick if she didn’t stop singing hymns? Why were the police called to halt a children’s baseball game? These were intriguing questions, but they seemed extremely remote from my life.

A year later, on September 21, 1989, Hurricane Hugo flattened parts of my little town, McClellanville, thirty miles north of Charleston, and left the rest looking like a French battleground after World War I. My house weathered the winds and the twelve-foot storm surge; the homes of many of my friends did not. Life as we had known it was swept away.

I still catch myself referring to something that happened “during the storm” when what I really mean is five months, or ten months, or even eighteen months later. Only on the nightly news does disaster pass quickly. And when I recall the long trudge back to normality, the memories that haunt me are not the images that show up on television every year on September 21—shrimp boats in the streets, a house that floated fifty yards from its foundation—or the ones in our family album—umbrellas poking through holes in the roof, my baby daughter climbing a mountain of donated sweet potatoes, dead fish on the front steps. Instead I remember feeling flayed alive, and knowing that everybody else must feel that way too. It was as if the storm had stripped away every shred of the emotional padding that, in normal times, allows people to ignore pain, smile politely, and go about their daily routines. There was a sense that help would never come, that we were doomed to spend the rest of our lives foraging in the wilderness.

Help did come, of course. Lots of help. Huge trucks rolled into town carrying water, ice, donated socks, diapers, mattresses, generators, even sofas. Volunteers and National Guardsmen wielded chainsaws and power washers.

But almost before the first bag of ice had melted, suspicion and greed set in. The storm hit in the middle of a prolonged fight over whether to establish a new public school in the heart of the village. Many whites supported the local private school, established to resist integration, and they loudly opposed the idea. Blacks and whites who favored public education saw the struggle as a crusade for equal rights. And far from laying aside their differences after the storm, these factions quarreled more bitterly than ever.

Perhaps it is a natural human impulse to want to help the people most like oneself—after all, the basic motive behind relief efforts is the knowledge that something like this could happen to you. Yet I was shocked when white people in vans tried to press diapers and baby clothes on me and visibly recoiled when I suggested they take their donations to Lincoln High School, where harder-hit black residents could get them.

I sometimes found myself thinking about the earthquake and wishing I knew more. But I was working on a biography of the novelist Julia Peterkin, who revolutionized American fiction in the 1920s by writing seriously about the lives of black farming people. As I labored to pin down the source of her subversive genius, the struggles Peterkin dramatized were playing out all around me. Blacks and whites inhabited the same expanse of earth but lived in different worlds. The trauma of the disaster itself was magnified by the experience of subsisting in a blasted landscape, looking, day after day, at splintered trees and mangled houses. Two decades after the storm, these images still appear in my dreams.

When the Peterkin book was finally finished, I did some research on the earthquake. I wanted to know more about how black people reacted, but all of the letters and diaries I found had been written by whites. I decided to try my hand at fiction and make up characters to fill in the blanks. But as I found out more, my friend Steve Hoffius, a skilled historian and the author of a highly acclaimed novel for young adults, convinced me that at least in this case, truth was more interesting than fiction. Steve had just finished a novel about three young girls living in the aftermath of the hurricane, and the same questions that troubled me fascinated him. Why did city authorities set up a comprehensive system to provide food and shelter, only to dismantle it less than three weeks later? And why did the city council try to discourage further donations when people still needed help? Before long we were collaborating on a nonfiction book about the earthquake.

With Hugo we had seen firsthand the havoc nature can unleash. Yet the earthquake, by all accounts, was far more surreal. What was it like to see the ground under your feet writhing, spouting, and lurching? Was it really true that the earth trembled for thousands of miles around? Could we verify bizarre reports that boggled the imagination? One by one, we checked out the stories. Most of the strangest proved to be true.

EVERY TIME A new disaster hit the news, Steve and I watched as governments tripped over each other trying to provide relief. People were fed and sheltered. Houses, schools, and businesses were rebuilt. While many questioned whether various agencies were responding in the correct way, no one debated, as they had in 1886, whether state and national governments should come to the rescue. In that sense, public attitudes have changed dramatically. But in another, more primal, sense, the trajectory of human emotions has stayed remarkably constant. After the Indonesian tsunami, after Hurricane Katrina, and even after the attacks of September 11, 2001, conflicts that had simmered before the cataclysm came back in more virulent forms, just as they had after the Charleston earthquake. The initial surge of harmony gave way to resentment, paranoia, and spite.

FOR YEARS Steve and I hunched over microfilm readers and blurry photocopies of century-old newspapers, trying to understand the dynamics of the city that was shattered by the earthquake. The details were endlessly absorbing, artifacts of a forgotten time that came to life in the pages of the Charleston News and Courier.

The editor of that paper, Francis Warrington Dawson, was the hero of the earthquake. He led the relief effort, rebuilt morale, and controlled much of what the rest of the world heard about the crisis. Standing amid the rubble of his newspaper office, Dawson predicted that Charleston would build a new city on the ruins of the old. The calamity, he declared, would bring people closer together. But as New Orleans reminded the world after Hurricane Katrina, natural disasters do not erase old conflicts. They reveal dirty secrets.

Born and raised in England, Dawson had a broader vision than almost anyone else in Charleston. He consulted with presidents and recog...