![]()

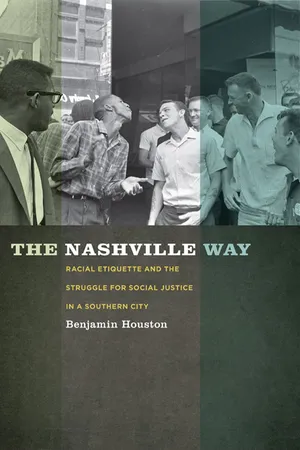

THE NASHVILLE WAY

Racial Etiquette and the Struggle for Social Justice in a Southern City

BENJAMIN HOUSTON

![]()

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Introduction. The Nashville Way

One. A Manner of Segregation : Lived Race Relations and Racial Etiquette

Two. The Triumph of Tokenism : Public School Desegregation

Three. The Shame and the Glory : The 1960 Sit-ins

Four. The Kingdom or Individual Desires? : Movement and Resistance during the 1960s

Five. Black Power/White Power : Militancy in Late 1960s Nashville

Six. Cruel Mockeries : Renewing a City

Epilogue. Achieving Justice

Notes

Bibliography

Index

![]()

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book has been with me for a long time and through a lot of changes. There are tons of people to thank, personally and professionally.

I gratefully acknowledge the financial support that underwrote major parts of the research and writing of this book. The McLaughlin Grant from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, University of Florida, was absolutely critical in providing a summer of intensive research in Nashville. A Dissertation Writing Fellowship from the Louisville Institute was similarly significant in allowing concentrated energy and attention to completing the first draft. Smaller but valuable grants from the Southern Baptist Library and Archives, Emory University, and Georgia State University, plus the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson presidential libraries, permitted me to explore important research angles. The Center for Africanamerican Urban Studies and the Economy (CAUSE) at Carnegie Mellon University generously supported my ongoing research agenda, as has Newcastle University. I also thank folks at Edinburgh, Sunderland, and Cambridge Universities for chances to present my work and talk through my findings. Similarly, I’m grateful to the staff and fellows at Harvard University’s W. E. B. Du Bois Institute, sponsor of the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Summer Institute on civil rights, for a month of intensive thinking and study. All created tremendous opportunities for me.

I would also like to acknowledge those in Nashville who were incredibly supportive. George Barrett welcomed me with dozens of stories and insights, and I thank him for his boundless generosity (and for the cigars). Don Doyle and Marjorie Spruill graciously opened their home during a summer of research, making an immense difference during my Nashville jaunt. Pete Kuryla and Bob Hutton were especially fantastic in welcoming me to the city, talking shop and hilarious nonsense in equally entertaining measure. And I am most appreciative of those who were agreeable to being interviewed or pointed me in new directions. Similarly, I cannot thank enough all the fantastic archivists who rolled up their sleeves and helped a rookie researcher immerse myself in Nashville’s documentation. I particularly am grateful to Kathy Smith and Teresa Gray at Vanderbilt, Beth Howse at Fisk, Ken Fieth at the Nashville Metro Archives, Kathy Bennett and Sue Loper at the Nashville Public Library, and Chris Harter at Amistad Research Center. Beth Odle at the Nashville Public Library was particularly patient in helping me find the right photos for this book.

In direct and indirect ways, the driving interest in this book first stirred at Rhodes College. Tim Huebner saw something and worked indefatigably for my sake more than his, and I thank him for the belief. Russ Wigginton gave me a first peek at the civil rights movement; he and Doug Hatfield gave sage advice freely. Even before that, I carried a bit of Paul Hammock’s and Doreen Uhas-Sauer’s influence on me wherever I went, and still do—thank you for what you did. As a dissertation, this project was birthed at the History Department at the University of Florida, where I had the great fortune of working with great people and scholar-teachers. Julian Pleasants is a good man and had my back in a number of ways. Roberta Peacock looked after me in many different ways. Bert Wyatt-Brown, Fitz Brundage, and Jack Davis were very good role models for me in various ways, and I thank them for their energy and support. And special thanks especially to mate and tireless mentor, Brian Ward.

I’m also grateful for all the UF gang : Jenny, Jace and Shannon, Craig and Amanda, Sonya and Barclay, Carmen, Bud and Theodora, Jason, Mike, Tim, Kristin, Randall, Kim, Bryan, Dave, and Chris—good times and fine people all the way around. Alan and Lynn were exceptional for their wisdom, caring, and hilarity, and triple thanks to Barclay for enduring all those damn e-mails. Professionally, I would also like to mention Wesley Hogan, Tony Badger, Ray Arsenault, Jane Dailey, Mike Foley, Bill Link, Ellie Shermer, Mike Ezra, Clive Webb, George Lewis and Liz Gritter for advice and good sense in varied capacities, as well as the good folks at the University of Georgia Press.

Working at the Carnegie Mellon’s Center for Africanamerican Urban Studies and the Economy was a tremendous first job. Thanks go to Joe Trotter, a fine man and consummate professional who taught me a lot. I’m also grateful to Tera Hunter, Johanna Fernandez, Edda Fields-Black, John Soluri, Nancy Aronson, Allen Hahn, and Jared Day for welcoming me to the school and the profession. Similar thanks go to Kevin, Russell, Lisa, and the rest of the graduate students for their cheerful energy, with special appreciation to Kate Chilton and Alex Bennett for able research assistance. Lisa Hazirjian and Derek Musgrove were especially splendid comrades/colleagues/friends and, in the case of “Gee, Derek,” a sorry excuse for a beer drinker but a very fine voicemail leaver.

Shifting across the pond to teach in England has landed me among a lot of amazing people. Hot-water bottles were just the start from Martin Dusinberre, but now that I’ve thanked him in print, I can stop checking my phone and he can stop killing me in squash. Saying thank you is simply inadequate for Joe Street, Martin F., Felix, Xavier, Asuka, Susan-Mary, Carolyn, Lorenzo, Matt, Monica, Alex, Sam, Claudia, Joan, Tim, Samiksha, Di, Kate, Mike, David, and Scott, but I hope they know that I mean it. Thanks also to the Friday footy crew for enduring my sad attempts at being a striker and for the ales afterward. Now that the book is done, I can safely exhort : “Long live Big W”!

On a more personal note : thanks to Melanie Sylvan, Heather Sebring, Andrew Vlahutin, Christine Leong, B.J. and Andrea Yurcisin, and Brandon and Trudy Barr for letting me crash on sofas during various research trips and always being there, in so many rich and amazing ways. Thanks for reminding me where I came from and where I could go. Much love to Nikolai and Ellen, who more than anyone can keep me balanced (and I’m sorry about the printer), and to Lori for the e-mails, laughter, and moral support. This book is dedicated to Robert J. Houston and Evelyn Yurcisin Houston, my parents. Both of them taught me about history in very different but hugely important ways. Their sustenance and love was manifested every day in a thousand large and small examples.

And finally : Michelle. It’s not just any person who on any given day can and will proofread my chapters, give me a yoga lesson, help me thrash out ideas over a pint, or bring me countless cups of coffee as I furiously pound away on a keyboard. That’s just a fraction of what she does. Yet, who she is, and what she has brought to my life, is even more luminous.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

The Nashville Way

These aberrations are kept going more by unwritten and un-writable laws than by the written law affecting the races : by an immense and elaborate code of etiquette that governs their daily relations; by an exquisite and intuitive tact on the part of both whites and Negroes; by adherence to a labyrinthine code of manners, taboos and conventions. There is therefore a sense of strain in the air, of a delicately poised equilibrium of forces held in leash. Here men toss uneasily at night, and awake fatigued in the morning.

—David L. Cohn, “How the South Feels,” 1944

Among all the vivid examples of Jim Crow–style segregation in the South, some of the ugliest were the stark WHITE and COLORED signs paired with shiny or shabby restrooms and water fountains. As powerful symbols of the racial divide, these markers were all the more chilling for being so casual. And yet, for someone strolling through downtown Nashville in the 1940s, those signs were not always there, forcing the visitor to chart a far more bewildering path. No WHITE or COLORED designations adorned the restrooms in the state capitol, for example. Nor were there any in the post office, where both races waited in line together—although the watchful eye would note that black postal employees always worked in the back room under white supervision but never at the service window.1

Walking through the city-county building downtown, however, yielded mixed messages. The upper floor did have segregated restrooms, but no one bothered to ensure that people obeyed the mandate. The first floor instead had what used to be a COLORED sign, painted over because of a lack of white facilities, alongside a water fountain used by both races. Similarly, in one railway station where some whites worked side by side with blacks, the restrooms were segregated but “similarly equipped” and a common water fountain served both races. At the customs house, the COLORED restroom for black employees was considered well-appointed despite being segregated—but the public restrooms and water fountains were used by both races. For audiences at the city auditorium, the color line switched invisibly depending on the crowd : sometimes blacks were relegated to balconies, but other times both floors were divided, with the poorer of both races up in the cheaper seats. And while Nashville courtrooms did not have racially designated seating, “Negroes always discreetly leave a foot or more of space between themselves and whites.”2

In myriad ways, an important aspect of race’s legacy in modern U.S. history is how space and place were preserved or rearranged by whites and African Americans in large and small dimensions. As both races went about their lives, the South’s social dynamics loomed conspicuously in even the most routine interracial interaction. In a Nashville courtroom, the quiet use of gaps between people seated on a bench had far deeper meaning as an expression of social distance. But, on a vaster scale, the molding of various spaces into black and white neighborhoods told equally important stories about how economic and political clout constructed laws and public policies that shaped and reflected the social dynamics of Nashville.

This book is an account of how two races in one city, with a shared history yet divergent paths, utilized and fought over social and physical space in diverse ways. Within that story is ...