![]()

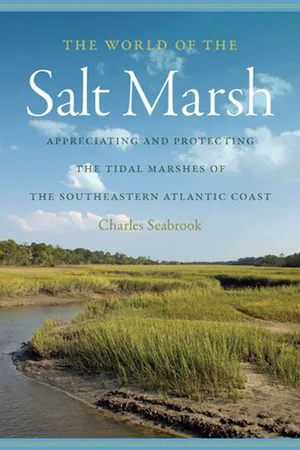

THE WORLD OF THE SALT MARSH

Appreciating and Protecting the Tidal Marshes of the Southeastern Atlantic Coast

CHARLES SEABROOK

![]()

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Introduction

ONE. The Poetry of the Marsh

TWO. A Walk across the Marsh

THREE. Tide Watching

FOUR. Too Big for Its Britches

FIVE. Farms in the River

SIX. Gone with the Flow

SEVEN. A Tale of Two Rivers

EIGHT. An Endangered Culture

NINE. The Institute

TEN. Protecting the Marsh?

ELEVEN. Saving the Oyster

TWELVE. Saving the Marsh

THIRTEEN. Rice Fields and Causeways

FOURTEEN. Bridging the Marsh

FIFTEEN. The Ultimate Price

SIXTEEN. Living on the Edge

SEVENTEEN. The Last Season

EIGHTEEN. The Beloved Land

Epilogue

Notes

Index

![]()

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EVERY PERSON WHOSE NAME appears on these pages deserves my considerable thanks for their guidance and kind advice during the research for this book. To name everyone who graciously helped me, though, would require the equivalent of another chapter. I am grateful to them all. I must, however, express my special gratitude to some very helpful individuals: Ron Kneib, Merryl Alber, and Lawrence Pomeroy at the University of Georgia; Fred Holland at the Hollings Marine Laboratory in Charleston; Charlie Phillips, fishmonger and airboat pilot supreme; library director John Cruickshank and public information director Mike Sullivan at the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography; James Holland of the Altamaha Riverkeeper; Larry and Tina Toomer, co-owners of the Bluffton Oyster Company; and my fellow board members of the Center for a Sustainable Coast—Dave Kyler, Charlie Belin, Steve Willis, Peter Krull, Mindy Egan, Les Davenport, and Ellen Schoolar.

Many thanks to Christa Frangiamore, Judy Purdy, and Laura Sutton, who as editors at the University of Georgia Press encouraged me to pursue the book when it seemed a daunting task. Thanks to Mindy Conner for her skilled editing. And thanks to the entire UGA Press staff for their talent and professional ability.

Finally, thanks to my wife, Laura. Without her, I would be an aimless wanderer.

![]() THE WORLD OF THE SALT MARSH

THE WORLD OF THE SALT MARSH![]()

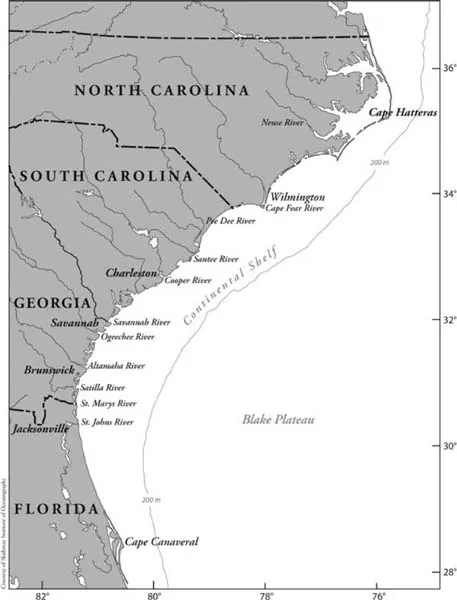

The South Atlantic Bight is an indentation in the coastline stretching roughly from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to Cape Canaveral, Florida, and encompassing the continental shelf offshore.

Map by Anna Boyette at the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

I SPENT HALF MY childhood trying to get off an island. I have spent half my adulthood trying to get back.

The island is John’s Island, one of the sleepy, semitropical sea islands nuzzling the South Carolina coast that are surrounded by vast salt marshes, broad sounds, and winding tidal rivers. It was home to my ancestors for two hundred years, a haven where everyone knew my name. My daddy once warned me how it would be when I left: “When you leave this island, nobody will give a damn whether your name is Seabrook,” he said.

But I could not wait to leave. There were soaring mountains with snowcapped peaks and tropical rainforests with wild, howling monkeys to see. I wanted to ride a camel across the Sahara and descend into deep caverns to gaze upon stupendous geological wonders. I wanted to see Paris, London, New York, Rio, Rome, Istanbul, and the thousands of other places I read about in National Geographic.

So, three days after graduating from high school in 1962, I left my island. Since then I have seen many of those places. As a science reporter for thirty-three years with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution I wrote stories from such far-flung places as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska and the rainforests of Guatemala. I walked on the Great Wall of China, paddled a dugout canoe down an Amazon tributary in Brazil, and rode through the Panama Canal in an outboard skiff. I saw Paris, Rome, London, Rio, Berlin, Beijing, Hong Kong, Prague, Budapest, and other marvels.

But I know now that the most wondrous, magical place of all was the place I left as soon as I got the chance—my island. I remember the moment when I finally realized that. I had been living for many years in Atlanta, and I was crossing the bridge to the island on a glorious autumn afternoon to see my mother. It was high tide, and the golden marsh with the tidal creeks twisting through it glowed softly in the afternoon sun. The beauty took my breath away.

An unnamed salt marsh creek in late summer on John’s Island, South Carolina.

The creeks, of course, have always wound through the marsh; the sun has always set over it. I just hadn’t appreciated the splendor of the view before. I was too busy plotting to get away. Now, after years of being away, I long for what I once took for granted.

In my boyhood, John’s Island—a twenty-minute drive from downtown Charleston—was a place of magnificent spreading live oaks dripping with Spanish moss that formed cathedral-like canopies over the sandy roads and pathways; of stately palmettos that rustled when nudged by the soft air; of the broad Stono River, now placid blue, now roiling green in mood with the sky. Dolphins frolicked in the water and rolled up on mud banks and then back into the water again. You could spend all day sailing the river or searching its high bluffs for arrowheads, rusting Civil War cannonballs, and long-lost pirate booty.

Anyone who flung a cast net into the tidal creeks pulled out bountiful shrimp, blue crabs, and mullet. Oysters crowded the creek banks and were there for the taking. At oyster roasts, we tossed the mollusks onto a redhot sheet of tin, threw wet croaker sacks soaked in salt water over them, let them steam several minutes, then shucked them open to get at the succulent meat.

On certain Sunday afternoons in summer, church members gathered at the river’s edge to witness as the preacher in hip boots dipped the white-robed baptismal candidates into the ebb tide, the best tide for washing away sins.

At church suppers, tables sagged with platters of juicy tomatoes and corn on the cob and steaming bowls of beans, peppers, peas, and collards. The island’s fertile black loam yielded a cornucopia of vegetables for anyone with the energy to drop a few seeds into the ground and do a little weeding.

There was something else, too: John’s Island was a stronghold of “cunjuh,” a brand of voodoo practiced on the sea islands. I believed in it as a child, and to this day I don’t challenge it. I lay in bed many a night and heard the cunjuh drums thumping on Whaley Hill, just across the salt marsh from my home. Nighttime was when the hags and the boodaddies and the plat-eye and the cunjuh world’s other sinister denizens came out.

Boodaddies were the spirits of dead people who had returned to Earth to take somebody back with them. If you saw a boodaddy, you were supposed to stand stock-still and say, “I ain’t ready to go yet.” The plat-eye, the all-seeing spirit, could appear as a pig, a calf, a yellow cat, or some other form, but all were distinguished by one formidable trait—a big, ugly eye hanging out the center of the face. Hags were invisible and could ride you and sap the strength from your body. They could come through a keyhole and sit on your chest and stop your breathing. Nearly every sound of the night was a hag omen. The soft creaking of a porch swing nudged by a light breeze was really a hag scratching around, trying to get in. A barking dog was being harassed by a hag. Even daytime sounds were signs that hags would be up and about that night.

“Hag gon’ come ’round tonight,” warned one of our neighbors, Sis’ Mamie, when a rooster crowed or an Air Force jet broke the sound barrier. Sis’ Mamie spoke in Gullah, the lilting patois that is unique to the sea islands and incomprehensible to outsiders.

As much as I long for my island, I can never return to the place I knew as a child. Its verdant maritime forests have given way to subdivisions and shopping centers and horse farms. Because of pollution, oysters no longer can be taken from many of the creeks. The beautiful Gullah dialect is dying out, victim of television’s pervasiveness and pompous educators who believe everybody should talk the same way.

Gone is John Isabull, who nearly every day—except Sunday—drove his wobbly, mule-drawn wagon down the road to a little field, where he unhitched the weary animal from the cart and hooked him up to a plow to cultivate sweet watermelons and other produce. John’s “gees” and “haws” at the stubborn old mule could be heard a mile away across the salt marsh.

Gone, too, is Mr. John Limehouse’s store, a wondrous place redolent of tobacco, smoked sausage, herring, and bananas. On sultry summer days it was pure pleasure to stick your hand in the drink box and feel around in the icy water for a Nehi grape soda or Coca-Cola. The old store was torn down to make way for a fancy convenience mart with self-serve gas pumps.

Long gone are the gypsies who came in the summer, three or four families in dilapidated cars pulling rickety wooden trailers. They set up a “carnival” and a tent in Mr. Limehouse’s pasture on the edge of the salt marsh and showed movies Monday through Friday nights. On Saturdays they staged a “rodeo” with a half-starved bull and some broken-down horses that were candidates for the glue factory. To a child who had never wandered far from the island, it was a glorious spectacle.

Our parents told us not to go to the camp by ourselves because the gypsies stole children. I believed that back then, just as I believed in the hags and the boodaddies. And now I long for my island. In my heart, I never really left it.

THE BEAUTY OF my island was undeniable even to a child. But I didn’t realize back then that the tidal marsh surrounding the island and backing up to our backyard is one of the most remarkable natural systems on Earth. The salt marsh has been described as a biological factory without equal—far more fertile than the fields in which we raised our tomatoes and soybeans, more productive than the great fields of wheat and corn in the Midwest called America’s breadbasket.

Twice a day, the tides ferry in a perpetual supply of nutrients, which the plants and microorganisms of the marsh break down and use with amazing quickness. The unfailing cycle nourishes the vast meadows of salt-tolerant Spartina alterniflora, or smoot...