eBook - ePub

From Knowledge Management to Strategic Competence

Assessing Technological, Market and Organisational Innovation

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Knowledge Management to Strategic Competence

Assessing Technological, Market and Organisational Innovation

About this book

There continues to be much interest in the business and academic communities in the concept of strategic competencies or core capabilities, in other words, how organisations define and differentiate themselves. More recently, this field has fragmented into a number of related disciplines with subtle differences in focus:

- Knowledge management — how organisations identify, share and exploit their internal competencies, in particular the knowledge of individuals.

- Organisational learning — the relationship between individual and organisational knowledge and how organisations ‘unlearn’ past competencies and acquire new competencies.

- Strategic management — how competencies can be assessed, and how these contribute to performance.

- Innovation management — how such competencies are translated into new processes, products and services.

This book aims to integrate strategic and knowledge management approaches to capability building with the development of competencies by bringing together the latest research and practices from international experts in the field. This third edition has been fully updated with five new chapters.

Contents:

- Strategic Competencies:

- Dynamic Capability and Diversification (Javad Noori, Joe Tidd and Mohammad R Arasti)

- What are Strategic Competencies? (Richard Hall)

- The Role of Dynamic Capabilities in Developing Innovation-Related Capabilities (Hanna-Kaisa Ellonen, Ari Jantunen and Olli Kuivalainen)

- Market Competencies:

- Brands, Innovation and Growth: The Role of Brands in Innovation and Growth for Consumer Businesses (Tony Clayton and Graham Turner)

- Technological and Market Competencies and Financial Performance (Joe Tidd and Ciaran Driver)

- Knowledge Management Routines for Innovation Projects: Developing a Hierarchical Process Model (David Tranfield, Malcolm Young, David Partington, John Bessant and Jonathan Sapsed)

- Technological Competencies:

- Indicators of Innovation Performance (Pari Patel)

- Assessing Technological Competencies (Francis Narin)

- The Complex Relations Between Communities of Practice and the Implementation of Technological Innovations (Donald Hislop)

- Organisational Competencies:

- Managing Competences to Enhance the Effect of Organisational Context on Innovation (Sebastien Brion, Caroline Mothe and Maréva Sabatier)

- The Organisation of “Knowledge Bases” (Jonathan Sapsed)

- Supplier Strategies for Integrated Innovation (Thorsten Teichert and Ricarad B Bouncken)

- Developing Competencies:

- Innovation: A Performance Measurement Perspective (Pervaiz K Ahmed and Mohamed Zairi)

- Learning and Continuous Improvement (John Bessant)

- Creating Value by Generative Interaction (Michael M Hopkins, Joe Tidd and Paul Nightingale)

Readership: Graduate students and professionals in the fields of business, innovation and knowledge management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Knowledge Management to Strategic Competence by Joe Tidd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Information Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

STRATEGIC COMPETENCIES

Chapter 1

Dynamic Capability and Diversification

Javad Noori

SharifUniversity ofTechnology, Iran

Joe Tidd

SPRU, University ofSussex, UK

Mohammed R. Arasti

SharifUniversity ofTechnology, Iran

Introduction

Dynamic capabilities are central to innovation strategy (Bessant and Tidd, 2011; Keupp et al., 2012), and yet, despite 20 years of development and many theoretical contributions, the conceptualization, operationalization, and application of the resource-based and dynamic capabilities views of strategic management remains problematic. For instance, there is no consensus definition of dynamic capabilities. There are various and occasionally contrary theories and explanations for diversification of firms (Cantwell et al., 2004). Practitioners also face significant challenges in determining diversification strategy and practice. These challenges become more fundamental when we consider firms in different contexts, e.g. stage of firm’s growth, firm size, characteristics of industry, development level of country, and corporate mission (Khanna and Palepu, 1997; Zhao, 2009). While resources are core elements in linking and co-ordinating strategy dimensions (Collis and Montgomery, 1998), there has been less research linking specific firm resources and capabilities with the ability to create and implement diversification strategies (Seppanen, 2009). In addition, there has been limited success in translating the concepts and research into management prescriptions and practice (Wijngaarde, 2008).

In this introductory chapter we have three primary aims. First, to review the related literature on resource-based, dynamic capabilities and diversification views, in order to better identify linkages and challenges. Secondly, to develop a conceptual framework that better integrates these three concepts, and therefore contributes towards operationalization, research, and practice. Finally, we test the utility of this framework by applying it to the case of a large multi-technology and multi-business industrial company which has undertaken apparently unrelated diversification over many decades. The chapter structure follows this logic: in the first section we propose a typology of resources and represent definitions and functions of dynamic capability. Then we review the literature on content and process dimensions ofbusiness diversification. The second section develops a new framework to help explain how technology-based business diversification, non-technological business diversification, and context influence business diversification. The final empirical section tests the proposed approach by applying it to the case of an industrial multi-business corporation.

Literature Review

The generic literature of corporate strategy is characterized by a diverse range of competing theories and alternative perspectives. Among these, four generic perspectives are dominant: industrial organization; game theory; resource-based view (RBV); and dynamic capabilities view (DCV) (Verburg et al., 2006). Both industrial organization and game theory approaches assume technology and other resources are exogenous factors to be incorporated in order to gain competitive advantage through the deployment of generic strategies (Porter, 1980, 1985). In contrast, the RBV and DCV define resources as aspects that induce the development of the strategy of the firm. Resources play an important role within the recognition and definition of competencies and capabilities. The translation of technology into business is important and recognized as crucial within the strategy process (De Wit and Meyer, 2005), in particular within large, multi-business firms (Trott et al., 2009). Consequently, we believe that RBV and DCV are the most appropriate approaches to investigate the corporate-level strategies like business diversification. We review the RBV and DCV literature and related work on business diversification in the two next sections.

RBV and DCV

The RBV proposes that competitive advantage is primarily driven by a firm’s valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources (Barney, 2001, 2002). Theunderlying assumption is that resources are heterogeneous across organizations and that this heterogeneity can sustain competitiveness over time.

Penrose (1959) provided initial insights into the resource perspective of the firm. Wang and Ahmed (2007) note that the RBV was first proposed by Wernerfelt (1984) and subsequently popularized by Barney (1991). Many authors (e.g. Zollo and Winter, 2000; Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Winter, 2003) have since made significant contributions to its conceptual development. Although the RBV as a theoretical framework helps to explain how firms achieve competitive advantage and create value, it does not adequately detail how firms do that in the context of fast-changing environments (Lockett et al., 2009). The value of resources will depend on context, and their change and adaptations often lag behind environmental changes (Teece et al., 1997). In rapidly changing markets, a dominant focus on core resources may create rigidities that prevent firms from adapting their resources to the new competitive environment (Leonard-Barton, 1992).

As a result, the RBV has been refined to the DCV, in which capabilities augment the role of resource to “integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece et al., 1997). From this perspective, firms must adapt, integrate, and reconfigure their resources and competencies continuously in response to changing market conditions. Whilst some scholars assert that the resource- based view includes dynamic capabilities (Furrer and Goussevskaia, 2008), the strategy literature generally considers dynamic capabilities as a complement to the RBV, but shares similar assumptions (Wang and Ahmed, 2007; Furrer et al., 2008). Therefore, it is important to more clearly differentiate the concepts of resources and dynamic capabilities, and the relationship between them.

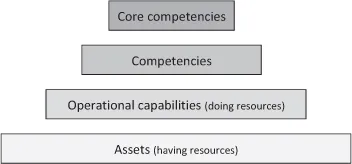

Resources are stocks of available factors that are owned, controlled, or accessed on a preferential basis by the firm (Amit and Schoemaker, 1993; Collis, 1994; Helfat etal., 2007). Resources canbein having (stock) or doing (flow) forms (Hall, 1992, 1993; Katkalo et al., 2010). “Having” resources are both tangible — like location, material, building, inventory, machinery, and low-skill people — and less tangible — like patents, databases, licenses, brand, and copyright. These resources are normally available to most firms, tradable in the market, and exogenous. In contrast, “doing” resources are intangible — skill-based, firm specific, not tradable in market — and endogenous. Examples of “doing” resources are capabilities incorporated in organizational and managerial processes, like product development, technology development, and marketing.

Capabilities refer to the organization’s potential for carrying out a specific activity or setof activities (Fernandez etal., 2000; Galbreath, 2005). Collis (1994), while noting that it is difficult to categorize capabilities, presents three categories: abilities that help in performing basicfunctional activities of the firm; abilities that help in dynamically improving the activities of the firm; and abilities involving strategic insights that can help firms recognize the intrinsic value of their resources and develop novel strategies ahead of their competitors (Katkalo et al., 2010). He also distinguishes between a first category of capabilities, which reflect an ability to perform the basic functional activities of the firm, and a second category of capabilities, which deal with the dynamic improvement to the activities of the firm. Zollo and Winter (2002) and Winter (2003) also differentiate between operational (zero-order) and dynamic (first-order) capabilities. Operational capabilities are geared towards the operational functioning of the firm, including both staff and line activities; these are “how we earn a living now“ capabilities. Dynamic capabilities are dedicated to the modification of operational capabilities and lead, for example, to changes in the firm’s products or production processes. This classification has increasingly been adopted in recent models of dynamic capabilities (e.g. Helfat and Peteraf, 2003; Zahra et al., 2006).

Aggregation of resources gives another insightto resource classification. Assets are disaggregated and undifferentiated inputs to organization, while competencies and core competencies are more aggregated and leveraged types of resources. Core capabilities are also an aggregated and leveraged bundle of lower operational capabilities. For instance, system integration is a core capability that includes many operational capabilities, like project management, product and process development, marketing, and technology management (Praest, 1998; Blum, 2004; Ljungquist, 2007). Authors have proposed a schematic framework for resource classification (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Resource base of the company, a hierarchical classification.

The dynamic capabilities view originates in spirit from Schumpeter’s (1934) innovation-based competition where competitive advantage is based on the creative destruction of existing resources and novel recombination into new operational capabilities. These ideas were further developed in the literature, such as architectural innovation (Henderson and Clark, 1990), configuration competence, and combinative capabilities (Kogut and Zander, 1992). Extending these studies, Teece et al.’s (1990) working chapter is widely accepted as the first contribution developing explicitly the notion of “dynamic capabilities”. Despite being one of the most widely used and cited concepts, the central construct of dynamic capabilities is not well or universally defined. Teece et al.’s original definition as “the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” is rather broad and difficult to operationalize, so many authors have since offered their own definitions of dynamic capabilities (Table 1).

Some other scholars indicate the functions of dynamic capability without defining the DCV directly. In other words, they ask “what does dynamic capability do?” instead of “what is dynamic capability?” Different functional interpretations include:

•Inside-out capabilities, outside-in capabilities, and spanning capabilities (Day, 1994);

•reconfiguration processes, leveraging existing resources, learning, and creative integration (Ambrosini and Bowman, 2009);

Table 1. Dynamic capabilities: Definitions and functions.

Study | Definition and functions |

Teece et al., 1990; working chapter. | The firm is somewhat richer than the standard resource-based view ... it is not only the bundle of resources that matter, but the mechanisms by which firms learn and accumulate new skills and capabilities, and the forces that limit the rate and direction of this process. |

Teece and Pisano, 1994; first formal published chapter on DCV. | The subset of the competencies an... |

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- HalfTitle

- AuthorTitle

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface to the Third Edition

- Contents

- Part I. Strategic Competencies

- Part II. Market Competencies

- Part III. Technological Competencies

- Part IV. Organisational Competencies

- Part V. Developing Competencies

- Bibliography

- Index