![]()

Chapter 1

Musing

I am sitting in my study at home, letting my thoughts range freely from one topic to another. Before me there is a wall of books — fiction and non-fiction, scientific and non-scientific — and I try to estimate how many hundreds of years of human effort went into their production. Idly I transfer my gaze to the scene outside the study window and contemplate the bare branches of the trees on the nearby golf course. The New Year has just begun and winter must complete its course before fresh green leaves appear once more. Beyond those trees, some 200 miles away to the south, is London, where my daughter and her family live; they are due to visit next month and I look forward to seeing them all again.

When spring eventually arrives my wife and I will embark on a round-Britain cruise taking in various Scottish Isles, Dublin, the Channel Islands and London. As we get older we have become less adventurous and restrict our travelling to Europe — and the closer parts of Europe at that. In years gone by we travelled much more widely. We went many times, on a biennial basis, to China where I had scientific collaborators who were, and still are, my friends. Our longest journey together was to a conference in Perth, Australia, in 1987. It was an enjoyable visit and put to rest many misconceptions. There was no feeling of isolation there; on the contrary one felt part of a lively and vibrant community. We much admired, and somewhat envied, the quality of life we found in Perth. From Britain one cannot travel much further than that in this finite world of ours. To travel further one must leave the world and that is a privilege of the very few.

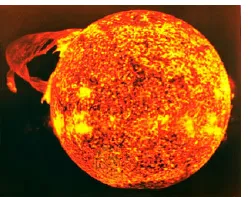

Not long ago I listened to a radio discussion about plans for new manned missions to the Moon and the aspirations of the various space agencies, including that of China, to send men to Mars. I wonder how feasible that really is. The discussion was detailed, and involved experts in the field, but one topic that seemed to be absent was that of the safety of the people involved. The Sun is a very active body. In its quieter periods there is a solar flare (Figure 1.1) about once per week. Every eleven years or so it goes through a more violent phase when solar flares tend to be larger and may occur several times a day. Solar flares are violent explosions on the surface of the Sun, releasing large quantities of very hard, penetrating X-rays and energetic charged particles, particularly protons, which are also very penetrating. The most violent solar-flare eruptions, called X-class flares, can have a major effect on terrestrial activities, despite the strong shielding effect of the Earth’s atmosphere. In 1989 an X-class flare caused a widespread power failure in the Canadian province Quebec and an even stronger flare, on 12th November 2003, disrupted radio communications in California and subjected astronauts, and even some air passengers flying in the stratosphere, to X-ray doses equivalent to that from a medical chest X-ray. Fortunately the main blast from that particular flare was not towards the Earth! Space suits give little protection from the most penetrating solar-flare radiation and spacecraft give partial, but not complete, protection. Scientists working on the International Space Station have been exposed to radiation levels well above average terrestrial levels for long periods without noticeable harmful effects. Nevertheless, it seems uncertain that astronauts, spending a year or so in space to get to Mars and back, could be adequately protected against unexpected major solar flares, especially if the maximum radiation output was in their direction. There are no such problems with unmanned missions although the working of scientific instruments can be, and has been, affected by radiation from solar flares.

Figure 1.1 A large solar flare (NASA).

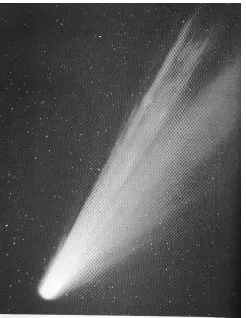

Spacecraft have explored to the outermost reaches of the Solar System; since their launches in 1977 the Voyager I and II spacecraft have left the region of the planets and are at a distance of more than 100 astronomical units from the Sun, where an astronomical unit is the average Sun–Earth distancea. The boundary of the Solar System is not something that can be defined with certainty. Beyond Pluto, once considered the furthermost planet but, since 2006, demoted to the status of ‘dwarf planet’, there exists a swarm of small bodies at least one of which, named Eris, is larger than Pluto. This region, known as the Kuiper Belt, stretches an unknown distance outwards from the Sun. What is known is that, orbiting the Sun at distances of tens of thousands of astronomical units, there are comet-like bodies, estimated to number 1011,b (one hundred thousand million), in a system known as the Oort Cloud. Once in a while these bodies are gravitationally nudged by passing stars, or other massive astronomical objects, and then some of them are pushed into orbits taking them close to the Sun, when they are observed from Earth in the familiar form of a comet, as seen in Figure 1.2. An average of about one comet per year is produced in this way, although most of them are not very spectacular and can only be seen with telescopes.

If the Oort Cloud is considered to be a part of the Solar System then the system stretches out a large fraction of the way to the nearest star to the Sun, Proxima Centauri. This is at a distance of 270,000 astronomical units. However, when we consider the distances of stars, or entities even further away, the astronomical unit is an inconveniently small unit of distance. In astronomy, and indeed in life in general, one always has the problem of comprehending quantities of interest. Most people have a reasonable idea what a kilometre represents in terms of distance, so that when told that York is 320 kilometres from London they can relate to that information. However, although most people also have a reasonable idea what a centimetre is, they would less readily relate to the information that York is 32 million centimetres from London. Similarly we better understand the performance of an athlete when we are told that he has run 100 metres in 10 seconds than if we were told that he had run 10,000 centimetres in 1.1574 × 10−4,c days. To some extent it is a matter of what we are used to, but it also depends on the fact that we have a better feel for the meaning of small numbers than for those that are either very large or very small. In astronomy, when distances of stars or other distant objects are concerned, the light year is a convenient unit. It is the distance that light travels in a year and, since the speed of light is 300,000 kilometres per second and there are 3.156 × 107 seconds in a year, the light year is about 9.5 × 1012 kilometres. On that scale Proxima Centauri is 4.2 light years from the Sun. When we are looking at Proxima Centauri we are seeing it as it was 4.2 years ago. If it were suddenly to explode then we should find out that it had done so 4.2 years after the event.

Figure 1.2 Comet West (1976) showing twin tails.

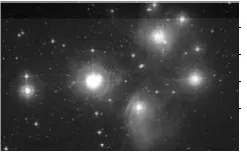

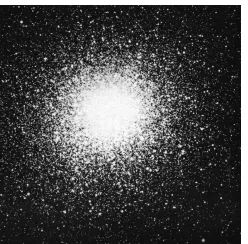

The Sun is what is known as a field star, which is to say that it moves through space without stellar companions. About two thirds of all stars exist in the form of binaries, which are pairs of stars that orbit around each other. These binary pairs can also have the property of field stars in that they travel without other companions. However, not all stars are field stars and large numbers of them exist within clusters, of which there are two main kinds. The first of these consists of anything from a hundred to a few thousand stars and these are known as open clusters or, sometimes, galactic clusters. A very beautiful example, shown in Figure 1.3, is the Pleiades cluster. This is a cluster of about 500 stars of which seven are very bright, and there are biblical references to it. The bright stars give the cluster its alternative name Seven Sisters, a name derived from Greek mythology. There are also much larger associations of stars, known as globular clusters, containing many hundreds of thousands of stars. One example, with the rather unromantic name M13, is shown in Figure 1.4; individual stars cannot easily be seen in the heart of the cluster but are visible in the outer regions.

Figure 1.3 The Pleiades, an open cluster.

Figure 1.4 The globular cluster M13.

Actually, there is a sense in which the Sun can be considered as a member of a cluster, the cluster being the Milky Way galaxy which is about 100,000 light years across from one side to the other. This is a collection of one hundred thousand million stars forming a recognisable association that is well separated from anything else. It contains field stars like the Sun, isolated binary stars, many open clusters, many globular clusters, clouds of gas and dust and many exotic objects such as neutron stars and black holes — of which more later. The space between these objects is known as the interstellar medium (ISM) — a crude description of which is that it is nearly nothing — but not quite. In a volume of the ISM the size of a sugar cube there will typically be one hydrogen atom. In the same volume of the air that you breathe there are about 1020 nitrogen or oxygen atoms. A very important component of the ISM is dust. This dust is in the form of particles less than one micron (one millionth of a metre) in diameter. A layer of 50,000 of them would comfortably fit in the dot above the letter i. If we consider a cube of the ISM of side one kilometre then that volume would contain just one dust particle! So little — is it even worth mentioning? Yes it is, because this dust plays a vital role in many astronomical processes. In particular it is the stuff that we human beings are made of!

Figure 1.5 The galaxy NGC 6744 — very much like our own Milky Way galaxy.

In saying that the Milky Way is well separated from everything else, we were implying that there are other things from which it is separated. These other things are other galaxies — some like the Milky Way, some bigger, some smaller, some of similar shape and some very different. The structures of nearer galaxies can be clearly seen with large telescopes, and one that resembles the Milky Way, the spiral galaxy NGC 6744, is shown in Figure 1.5. At their greatest distances, hundreds of millions of light years away, galaxies are seen as faint, fuzzy objects. The more powerful the telescope we use, the more galaxies we can see at ever greater distances. These bodies constitute for us the ‘observable Universe’, estimated to contain 1011 galaxies.

How did the Universe and all the objects in it — galaxies, black holes, stars, planets, satellites and many other kinds of object — come into existence? In particular, how did it come about that I am here looking through my study window and thinking about these things?

a One astronomical unit is approximately 150 million kilometres or 93 million miles.

b 1011 represents eleven 10s multiplied together or 100,000,000,000.

c 10-4 represents 1/104 or 0.0001.

![]() The Universe

The Universe![]()

Chapter 2

Christian Doppler and His Effect

2.1 Waves, Frequency and Wavelength

A piano keyboard is an arrangement of white and black keys strung out in a line. A key struck towards the left-hand edge of the keyboard gives a low, booming note — described as being of low pitch. At the right-hand edge the note is lighter, more buoyant in tone — described as being of a high pitch. Sound is a wave motion and, when we hear a sound, alternating high and low pressure air disturbances set the eardrum into vibration. These vibrations are processed and converted into electrical signals that are fed into the auditory cortex of the brain.

The term pitch is a qualitative way of describing the frequency of a sound wave — the number of vibrations per second. The scientific unit for frequency is the hertz (Hz), or one vi...