Environmental Applications of Nanomaterials

Synthesis, Sorbents and Sensors

- 752 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Environmental Applications of Nanomaterials

Synthesis, Sorbents and Sensors

About this book

This book is concerned with functional nanomaterials, materials containing specific, predictable nanostructures whose chemical composition, or interfacial structure enables them to perform a specific job: to destroy, sequester, or detect some material that constitutes an environmental threat. Nanomaterials have a number of features that make them ideally suited for this job: they have a high surface area, high reactivity, easy dispersability, and rapid diffusion, to name a few. The purpose of this book is to showcase how these features can be tailored to address some of the environmental remediation and sensing/detection problems faced by mankind today. A number of leading researchers have contributed to this volume, painting a picture of diverse synthetic strategies, structures, materials, and methods. The intent of this book is to showcase the current state of environmental nanomaterials in such a way as to be useful both as a research resource and as a graduate level textbook. We have organized this book into sections on nanoparticle-based remediation strategies, nanostructured inorganic materials (e.g. layered materials like the apatites), nanostructured organic/inorganic hybrid materials, and the use of nanomaterials to enhance the performance of sensors.

Contents:

- Nanoparticle-based Approaches:

- Nanoparticle Metal Oxides for Chlorocarbon and Organophosphonate Remediation (Olga B Koper, Shyamala Rajagopalan, Slawomir Winecki and Kenneth J Klabunde)

- Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron (nZVI) for Site Remediation (Daniel W Elliott, Hsing-Lung Lien and Wei-xian Zhang)

- Synthesis, Characterization, and Properties of Zero-Valent Iron Nanoparticles (Donald R Baer, Paul G Tratnyek, You Qiang, James E Amonette, John Linehan, Vaishnavi Sarathy, James T Nurmi, Chongmin Wang and J Antony)

- Nanostructured Inorganic Materials:

- Formation of Nanosized Apatite Crystals in Sediment for Containment and Stabilization of Contaminants (Robert C Moore, Jim Szecsody, Michael J Truex, Katheryn B Helean, Ranko Bontchev and Calvin Ainsworth)

- Functionalized Nanoporous Sorbents for Adsorption of Radioiodine from Groundwater and Waste Glass Leachates (Shas V Mattigod, Glen E Fryxell and Kent E Parker)

- Nanoporous Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Materials:

- Nature's Nanoparticles: Group IV Phosphonates (Abraham Clearfield)

- Twenty-five Years of Nuclear Waste Remediation Studies (Abraham Clearfield)

- Synthesis of Nanostructured Hybrid Sorbent Materials Using Organosilane Self-assembly on Mesoporous Ceramic Oxides (Glen E Fryxell)

- Chemically Modified Mesoporous Silicas and Organosilicas for Adsorption and Detection of Heavy Metal Ions (Oksana Olkhovyk and Mietek Jaroniec)

- Hierarchically Imprinted Adsorbents (Hyunjung Kim, Chengdu Liang and Sheng Dai)

- Functionalization of Periodic Mesoporous Silica and Its Application to the Adsorption of Toxic Anions (Hideaki Yoshitake)

- Layered Semi-crystalline Polysilsesquioxane: A Mesostructured and Stoichiometric Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Solid for the Removal of Environmentally Hazardous Ions (Hideaki Yoshitake)

- A Thiol-functionalized Nanoporous Silica Sorbent for Removal of Mercury from Actual Industrial Waste (Shas V Mattigod, Glen E Fryxell and Kent E Parker)

- Functionalized Nanoporous Silica for Oral Chelation Therapy of a Broad Range of Radionuclides (Wassana Yantasee, Wilaiwan Chouyyok, Robert J Wiacek, Jeffrey A Creim, R Shane Addleman, Glen E Fryxell and Charles Timchalk)

- Amine-functionalized Nanoporous Materials for Carbon Dioxide (CO 2 ) Capture (Feng Zheng, R Shane Addleman, Christopher L Aardahl, Glen E Fryxell, Daryl R Brown and Thomas S Zemanian)

- Carbon Dioxide Capture from Post-combustion Streams Using Amine-functionalized Nanoporous Materials (Rodrigo Serna-Guerrero and Abdelhamid Sayari)

- Nanomaterials that Enhance Sensing/Detection of Environmental Contaminants:

- Nanostructured ZnO Gas Sensors (Huamei Shang and Guozhong Cao)

- Synthesis and Properties of Mesoporous-based Materials for Environmental Applications (Jianlin Shi, Hangrong Chen, Zile Hua and Lingxia Zhang)

- Electrochemical Sensors Based on Nanomaterials for Environmental Monitoring (Wassana Yantasee, Yuehe Lin and Glen E Fryxell)

- Nanomaterial-based Environmental Sensors (Dosi Dosev, Mikaela Nichkova and Ian M Kennedy)

- Carbon Nanotube- and Graphene-based Sensors for Environmental Applications (Dan Du)

- One-dimensional Hollow Oxide Nanostructures: A Highly Sensitive Gas-sensing Platform (Jong-Heun Lee)

- Preparation and Electrochemical Application of Titania Nanotube Arrays (Peng Xiao, Guozhong Cao and Yunhuai Zhang)

Readership: Graduate students and researchers in nanomaterials and nanostructures.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Nanoporous Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Materials

Chapter 6

Nature's Nanoparticles: Group IV Phosphonates

6.1 Introduction

6.1.1 Natural nanoparticle formation

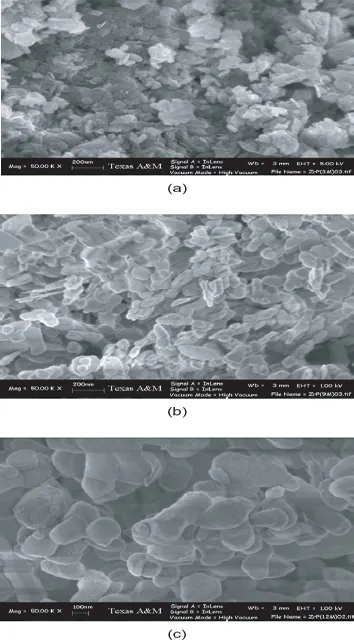

6.1.2 α-zirconium phosphate and nanoparticles

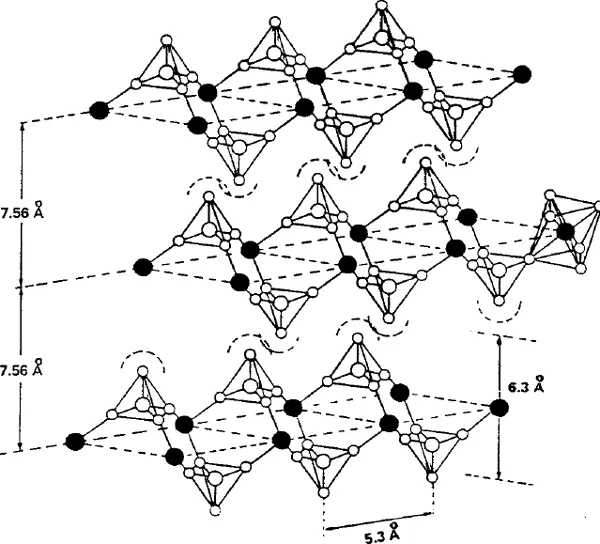

6.1.2.1 History and structure

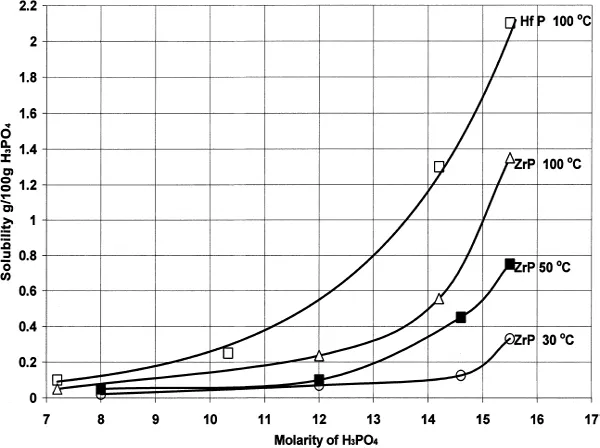

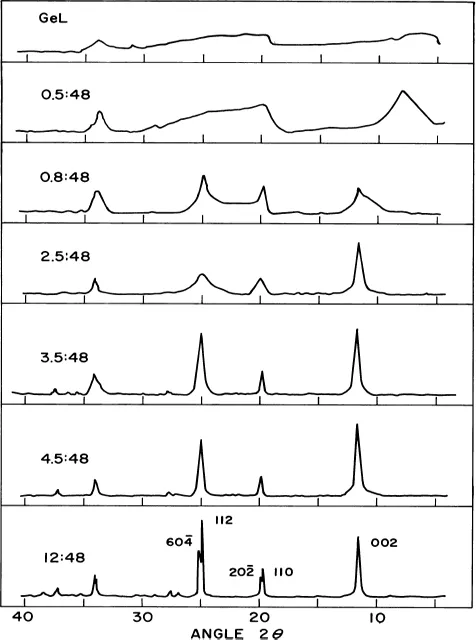

6.1.2.2 Crystal growth and ion-exchange behavior

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface to the First Edition

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Nanoparticle-Based Approaches

- Nanostructured Inorganic Materials

- Nanoporous Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Materials

- Nanomaterials that Enhance Sensing/Detection of Environmental Contaminants

- Index