![]()

Chapter 1

Learning in the Discontinuous Innovation Laboratory

John Bessant

University of Exeter Business School, UK

Research has consistently highlighted a set of themes which underpin an emergent good practice model for product and process innovation (Nelson and Winter, 1982; Pavitt, 2002; Tidd et al., 2005). Whilst this recipe needs adapting and configuring to suit specific contingencies, it can be argued that the core challenge has become one of implementation – getting individual enterprises to adopt and absorb such good practice. But the limitation of this good practice model is that it relates to what might be termed steady-state innovation – essentially innovative activity in product and process terms which is about ‘doing what we do, but better’.

So, for example, in product development the prescription is for close links throughout the process with users (getting them to act as innovators where possible), early and cross-functional involvement of key players inside and across the extended enterprise, concurrent working, effective project management (with particular emphasis on the team dynamics) and appropriate project structures and staged risk management via some version of the stage-gate model.

The prescription is not a good guide when elements of discontinuity come into the equation. Such discontinuous challenges arise from shifts along technological, market, political and other frontiers and require new or at least significantly adapted approaches to their effective management (Tushman and O'Reilly, 1996; Day and Schoemaker, 2000; Leifer et al., 2000). And, whilst we have some important clues from these and other studies, there is still a need to understand the particular contexts in which such approaches might help and the configuration of new practices within them.

The challenges centre on building routines – shared patterns of behaviour which become reinforced and embedded, eventually forming ‘the way we do things around here’. Adapting and changing routines to cope with shifting environments is at the heart of dynamic capability, and in the context of discontinuous innovation (DI) the kinds of issues raised include:

•How to pick up weak signals about discontinuity

•How to interpret the signals and generate an appropriate response

•How to avoid the ‘not invented here’ and other defensive responses

•How to assess risks associated with weak signals about potentially discontinuous change

•How to allocate resources to high-risk ventures

•How to manage projects so that there is fast failure and rapid learning

•How to manage discontinuous innovation across systems and networks – for example with diverse suppliers

•How to enable links between new ventures based on discontinuous change and the rest of the organization (ambidextrous capability).

One approach to dealing with this challenge involves putting together a network of firms acting as a co-laboratory for articulating key research issues around DI, sharing experiences and developing and implementing experiments to come up with new routines for dealing with it. Here, learning support comes through interaction and mutual support within a facilitated framework – it offers an example of a community of practice. The potential benefits of such shared learning include:

•Challenge and structured critical reflection from different perspectives

•Different perspectives can bring in new concepts (or old concepts which are new to the learner)

•Shared experimentation can reduce perceived and actual costs and risks in trying new things

•Sharing experiences can provide support and open new lines of inquiry or exploration

•Shared learning helps explicate systems principles, seeing the patterns – ‘separating the wood from the trees’

•Shared learning provides an environment for surfacing assumptions and exploring mental models outside of the normal experience of individual organizations – helps prevent the ‘not invented here’ and other effects.

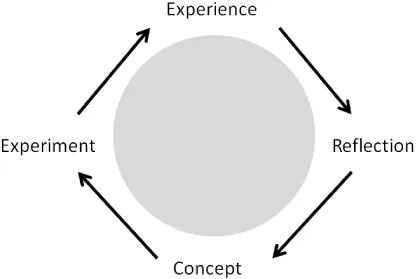

These approaches can be mapped onto a basic model of the learning process. Figure 1 shows the well-known experiential learning cycle originally put forward by David Kolb (Kolb and Fry, 1975). It views learning as involving a cycle of experiment, experience, reflection and concept development.

Fig. 1. Experiential learning cycle (Kolb and Frey, 1975).

Where an individual or firm enters is not important (although there is evidence for different preferred styles of learning associated with particular entry points). What does matter is that the cycle is completed – incomplete cycles do not enable learning.

Table 1 summarizes some of the key blocks to effective organizational learning, mapped onto Kolb’s learning cycle (Kolb and Fry, 1975).

Table 1. Key blocks to learning.

| Learning block | Underlying problem |

| Lack of entry to the learning cycle | Perceived stimulus for change is too weak

Firm is isolated or insulated from stimulus

Stimulus is misinterpreted, underrated or denied |

| Incomplete learning cycle | Motivation to learn is present but process of learning is flawed.

Emphasis given to some aspects – e.g. experimentation – but not to all stages and to sequence |

| Weak links in the cycle | Reflection process is unstructured or unchallenging

Lack of access to or awareness of relevant new concepts

Risk avoidance leads to lack of experimentation

Lack of sharing or exchange of relevant experiences – parochial search for new ideas

‘Not invented here’ effect |

| Lack of learning skills or structure | Lack of supporting and enabling structures and procedures |

| Knowledge remains in tacit form | Lack of mechanisms for capturing and codifying learning |

| Repeated learning | Lack of mechanisms for capturing and codifying learning leads to repetition of learning content |

| Learning is infrequent, sporadic and not sustained | Mechanisms for enabling learning are not embedded or absent |

Arguably, shared learning can contribute to dealing with some of these issues. It allows for both challenge and support, providing a framework in which elaboration and experimentation are enabled and through which individual and collective knowledge is built. In the management context it underpins what has become known as action learning, in which individuals help enable learning amongst their peers through a process of challenge, reflection, shared experimentation, etc. (McGill and Warner Weil, 1989). Revans (1983) suggested the idea of comrades in adversity, which refers to working together to tackle complex and open-ended problems (also see Pedler et al., 1991). There is growing interest in such approaches, for example the importance of individual-based networks and communities of practice in creating and carrying learning (Wenger, 1999; Brown and Duguid, 2000; Bogenrieder and Nooteboom, 2004). The underlying arguments relate to learning processes as ‘intrinsically social and collective phenomena’ (Teece et al., 1994), which provide mechanisms that allow shared experimentation, interpretation and codification, and which scaffold knowledge creation in practice (Cook and Brown, 1999).

Learning Networks around Discontinuous Innovation

In the context of DI, the Innovation Lab initiative was started in 2005 in three countries: the UK, Germany and Denmark. The Innovation Lab had a number of operating mechanisms; at the centre was a regular series of experience-sharing workshops (held at four-month intervals) at which participating firms were encouraged to report on their experiences (both positive and negative). The academic partners captured and synthesized this experience and fed it back via presentations and workshop activities during the meetings. The meetings reflected areas where existing innovation management routines had proved inadequate for dealing with DI challenges. Importantly, they brought together members of large and smaller companies from different sectors to work on common strategic and operational issues surrounding DI. Their experiences were documented by researchers from the academic institutions and augmented through case studies of member firms. In selecting cases, the research team requested that the firms identify innovations that they deemed discontinuous in nature.

This model proved successful in terms of maintaining participation, extending membership, developing useful tools and resources and moving the research agenda forward. One consequence was the decision to try to extend the model to other countries, essentially mirroring the overall operating structures of regular workshops interspersed with case study work with participating companies. Labs were subsequently organized in a variety of other countries and currently there are 16 in operation.

With the accumulating experience of so many players it became clear that extending the interaction to an international level would be useful and in 2006 the inaugural annual conference was held in London. This provided the opportunity for participants from Labs in different countries to exchange ideas and laid the foundation for a wider network. One consequence has been increasing traffic between the Labs so that, for example, a meeting in London might be attended by participants from Denmark, Germany and Ireland. There was also increasing company-to-company engagement; for example, after a presentation of the Philips experience in London an invitation was extended to present the work at the headquarters of a major Danish company.

The network continues to thrive and now involves around 300 companies and public sector institutions together with around 35 academic research teams. Full details can be found at our website, www.innovation-lab.org.

References

Bogenrieder, I. and Nooteboom, B. (2004). Learning groups: What types are they? A theoretical analysis and an empirical study in a consultancy firm. Organization Studies, 2(1), 40–57.

Brown, J. and Duguid, P. (2000). The Social Life of Information. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Cook, S. and Brown, J. (1999). Bridging epistemologies: ...