![]()

Chapter 1

On the Genesis of Problem Posing in Mathematics

1.1Problems from the first printed arithmetic

Problem posing has been used in mathematics education as a teaching method for quite a long time. It can be traced back to the 15th century when the first printed book on arithmetic, written (by an unknown author) for those students “who look[ed] foreword to mercantile pursuits” [Smith, 1959, p. 1], included real-life problems posed to explain how the rules of arithmetic work in trade. Connection of arithmetic to real life was then a new idea in mathematics education. In this bygone book, the rules of arithmetic were put in context in which numbers and operations on numbers could be used to describe concrete things and actions on them as related to trade. This is what the 21st century educators have been trying to do when explaining a physical meaning of the rules of multiplying and dividing fractions. It is through posing problems by our educational forefathers, who appreciated the applied nature of mathematics as a field of study, that the subject matter gained its applied flavor, although it is not clear whether they expected the meaning of arithmetical operations to stem from applications. According to Smith [1924], the problems posed in the 15th century book satisfied two major requirements: 1) a problem must be as much concrete as possible (e.g., in a problem about trade, assign names to merchants; a problem about travel includes references to well-known places and individuals); 2) a problem should have students practicing specific rules of arithmetic (e.g., to use the so-called rule of two things by multiplying and adding two given numbers and then dividing the product by the sum).

It should be noted that the emphasis on the formal use of such rules of arithmetic, as the rule of two things, points at the roots of teaching mathematics without understanding, primarily through drill and practice. In North America, until the second decade of the 19th century, the textbooks almost exclusively used the rule method grounded in pure memorization followed by drill and practice [Michalowicz and Howard, 2003]. This is what the modern-day mathematical teaching standards around the world have been trying to change. For one, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics [2000], the major professional organization of mathematics educators in North America, has been of the strong opinion that students should be offered “opportunities to learn important mathematical concepts and procedures with understanding” (p. 3). Likewise, more than half a century ago, at the very outset of mathematics education reform, progressive mathematics teachers in England advised “that teaching which tries to simplify learning by emphasizing the mastery of small isolated steps does not help children, but put barriers in their way” [Association of Teachers of Mathematics, 1967, p. 3]. Indeed, many applied problems published in the first book on arithmetic and reproduced by Smith [1924] would be considered quite challenging for a 21st century student if taught in a purely formal way, that is, through the use of rules one has to memorize but not necessarily understand. That is why, in what follows, a problem from the past will be used as an example to discuss modern methods of teaching mathematics with emphasis on the use of pictures, diagrams, and technology [e.g., Association of Mathematics Teacher Educators, 2017; Common Core State Standards, 2010; Conference Board of the Mathematical Sciences, 2012; Ministry of Education Singapore, 2012]. Consider a travel problem as presented in [Smith, 1924, p. 330].

Problem 1.1. “The Holy Father sent a courier from Rome to Venice, commanding him that he should reach Venice in 7 days. And the most illustrious Signora of Venice also sent another courier to Rome, who should reach Rome in 9 days. And from Rome to Venice is 250 miles. It happened that by order of these lords the couriers started on their journeys at the same time. It is required to find in how many days they will meet.”

Several questions have to be answered in connection with this problem.

Question 1. How can one solve this problem using the modern pedagogy of teaching arithmetic?

Question 2. How can one pose similar problems using conceptual understanding of the problem situation?

Question 3. How can one use technology to pose similar problems with friendly solutions?

1.1.1Solving a 15th century problem using the modern-day pedagogy

To answer the first question, let us assume (for simplicity) that the distance from Rome to Venice is the unit distance. While a reference to 250 miles adds concreteness to the problem, the use of this number does not affect the way its solution is structured. Also, one has to assume that both couriers walk with constant speed. In fact, this tacit assumption is true for all pre-calculus travel problems. Then the courier going to Venice will cover 1/7 of the distance in one day. Likewise, the courier going to Rome will cover 1/9 of the distance in one day. Here one can recognize the first appearance of fractions as a result of an operation on whole numbers. Note that 1/7 and 1/9 are not just unit fractions, they are rudiments of the concept of uniform movement establishing relation among distance, time, and velocity. Similar reciprocals of integers appear through solving the so-called work problems where, under certain assumptions, one’s capability of doing work can be interpreted as speed with which one moves.

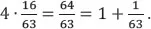

In order to facilitate students’ understanding of fractions, different visual methods of teaching are commonly used nowadays. With this in mind, through a two-dimensional model, used when two fractions are involved (1/7 and 1/9 in the case of Problem 1.1), the whole distance can be represented as a 7x9 rectangular grid with 63 identical cells (Fig. 1.1). To this end, the rectangle is divided both horizontally and vertically in seven and nine parts, respectively. Through the physical meaning of the two fractions, the very grid obtains its physical meaning as well. One can see that the faster courier can cover the whole distance (‘going’ from top to bottom) in seven days and the slower courier (‘going’ from left to right) can cover the whole distance in nine days.

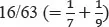

When moving towards each other within the grid (the virtual distance from Rome to Venice), the couriers cover

of the grid in one day. At the conclusion of the fourth day, they would have

covered the entire distance plus 1/63 of it (because the slower courier is short of one cell on the fourth day – the six non-shaded cells of the grid represent the distance left to the slower courier to cover on the fourth day). That is,

This means that they need less than four full days in order to meet. How can one represent an extra cell as a fraction of a day? There are 16 cells representing one day; therefore, one cell represents 1/16 of a day. Subtracting 1/16 from 4 yields an answer to the problem:

(days). Note that

which is the reciprocal of the fraction

– the distance covered by two couriers in one day. This means that the time till they meet is the reciprocal of the distance they cover in one day.

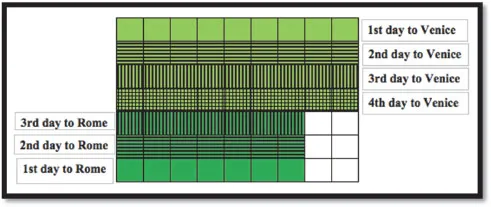

In order to better understand the meaning of the last statement, consider a simpler situation, when 1/2 of a distance is covered in one day. It is quite obvious that the whole distance will be covered in two days. Note that the number 2 (time) is the reciprocal of the number 1/2 (velocity) in our rudimental understanding of uniform movement. In the case of a non-unit fraction, one can use a one-dimensional model for fractions (

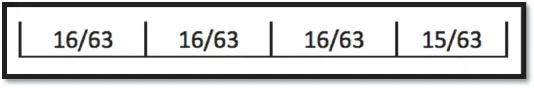

Fig. 1.2) to show how to move from one unit of measurement to another. In order to find what fraction of 16/63 (the measure of one day in terms of distance) is 15/63 (the far-right segment in

Fig. 1.2), one has to divide the latter fraction by the former one to get 15/16 (of a day). Once again, the answer is

(days). Alternatively, the answer can be given as 3 days, 22 hours and 30 minutes after calculating 15/16 of 24 in terms of hours and minutes.

Fig. 1.1. Solving the distance problem using rectangular grid.

Fig. 1.2. The sum of the four fractions is equal to one.

1.1.2Posing 15th century-like problems through conceptualization

Now we can answer the second question: how can one use our understanding of the problem situation in order to pose similar problems so that the number of days is an integer? Put another way, by asking this question, one poses the problem: When is the reciprocal of the ratio of the product of two integers to their sum an integer as well? This problem cannot be solved in a purely numeric milieu, without recourse to algebra. Algebraically, one needs to explore the equation

in which, in the context of Problem 1.1,

x and

y are two integers (things) involved in “the rule of two things” and

n is the (unknown) time the couriers need in order to meet somewhere between Rome and Venice. The last equation is equivalent to the equation

whence

For example, when n = 4 one of the solutions of (1.1) is x = 6, y = 12. One can construct the 6x12 grid, and using it as one whole, to see that it is comprised of four groups of 1/12 and four groups of 1/6.

Equation (1.1) has quite a long history going back to Babylonian mathematics (about 2000 B.C.). Indeed, when n = 2 equation (1.1) is equivalent to the following relation between “the two things”, xy = 2(x + y), and Babylonians knew how to find x and y [Van der Waerden, 1961]. Furthermore, the case n = 2 relates to finding rectangles with perimeter equal, numerically, to area, a problem known to Pythagoras1. For example, if x and y are integers which measure the side lengths of such a rectangle, then xy=2(x + y). Van der Waerden’s [1961] citation of Plutarch2 is worth mentioning in connection with this unexpectedly discovered situation: “The Pythagoreans also have a horror for the number 17. For 17 lies halfway between 16 … and 18 … these two being the only two numbers representing areas for which the perimeter (of the rectangle) equals the area” (p. 96). In other words, the equation xy=2(x + y) has only two solutions, x = y = 4 and x = 3, y = 6, representing 4x4 and 3x6 rectangles. Once again, each rectangle can be turned into a grid with the first one being interpreted as the case of two equal couriers covering the...