![]()

Chapter 1

The Dawn of a Science of Information

There is a revolution coming. It will not be like revolutions of the past. It will originate with the individual and with culture, and it will change the political structure only as its final act. It will not require violence to succeed, and it cannot be successfully resisted by violence. It is now spreading with amazing rapidity, and already our laws, institutions and social structure are changing in consequence. It promises a higher reason, a more humane community, and a new and liberated individual. Its ultimate creation will be a new and enduring wholeness and beauty – a renewed relationship of man to himself, to other men, to society, to nature, and to the land.

The revolution is a movement to bring man’s thinking, his society, and his life to terms with the revolution of technology and science that has already taken place. Technology demands of man a new mind – a higher, transcendent reason – if it is to be controlled and guided rather than to become an unthinking monster.

–Charles E. Reich, The Greening of America, 1970 –

Currently, a Science of Information does not exist. What we have is Information Science. Information Science is commonly known as a field that grew out of Library and Documentation Science with the help of Computer Science: it deals with problems in the context of the so-called storage and retrieval of information in social organisations using different media, and it might run under the label of Informatics as well. A Science of Information, however, would be a discipline dealing with information processes in natural, social and technological systems and thus have a broader scope. This is how the term Information Science is understood by a community of academics from different fields of science, engineering, humanities and arts who have been gathering around a conference series, a mailing list and a website with the abbreviation “FIS” (Foundations of Information Science) for more than a decade.

Currently, no (Unified) Theory of Information is available. Information Theory exists: it is a branch of mathematics and engineering science inaugurated by Claude E. Shannon’s paper “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” [1948]. That contribution dealt with the problem of keeping the signal–noise–ratio in communication transmission channels (hence the designation “channel” model) under control – a war-related problem. The entity that Shannon’s formalism intended to measure soon came to signify “information”. A (Unified) Theory of Information would have to deliberate about whether to generalise a framework that specifically focuses on syntactic aspects and omits semantic ones, yet reaches out to fields that require referring to semantics. This is precisely the brunt of many criticisms ever since. The result has been alternative theoretical approaches, none of which ever succeeded in being recognised by the overall scientific community as a more general Theory of Information that would, in fact, incorporate Shannonian Information Theory.

Equally, no unifying scientific information concept is available. We are accustomed to living with a multiplicity of diverse, and even contradictory, concepts of information. These are used throughout the edifice of natural, social and human, and engineering sciences, not to mention everyday thinking. Attempts to unify information concepts run the risk of getting caught in reductionism or its “twin”, projectivism. A convincing information concept would need to sidestep these traps.

A unifying information concept is the core of a Unified Theory of Information, which in turn is the core of a full-fledged Science of Information. Thus, the task of an as-yet-to-be-developed Science of Information is to study the feasibility of, and to advance, approaches toward a Unified Theory of Information and toward a unifying concept while constantly being aware of a potential failure of the project.

1.1 In the Tower of Babel

The fragmentation, heterogenisation, and disintegration of what today is understood by the term of information has historical preconditions.

1.1.1 The rise and fall of “information”

The usage and meaning of the notion “information” has changed over the course of history. Drawing upon Rafael Capurro’s seminal work of [1978], which is the ultimate source of reference, as well as on his later works on Angeletics, e.g. [2000, 2003], it appears that there has been an upward trend in the usage of the notion since Antiquity, that is an increase in incidence in the West. This was accompanied by a downward trend as to the meaning of the notion, that is a narrowing down of the range of objects signified and thus a thinning out of the contenta.

The roots of the notion of information lie in the beginnings of our civilisation – in Greek-Roman Antiquity. The Latin noun “informatio” and the Latin verb “informare”, because of its root syllable “forma”, refer back to the ancient Greek notions “typos”, “morphe” and “eidos/idea”? which mean the “stamped” or “stamping”, “shape”, “gestalt”, “form”. The verb “informare” therefore means “to shape something”, “to give form to something”, “to bring something into form”.

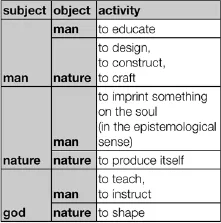

Antiquity and the following (scholastic) Middle Ages knew several connotations of the verb. They manifest a great variety of meanings depending on what the subject and what the object of the activity might be (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Meanings of “informare”

The following meanings can be distinguished:

(1) if the subject was man

(a) and the object was man, then “informare” signified the activity of educating (in the broad sense of the antique pedagogical meaning that included the shaping of morality through role models);

(b) and the object was nature, then the term meant designing, constructing, crafting (as in handicraft);

(2) if the subject was nature

(a) and man its object, it meant the activity of imprinting in the sense of gaining knowledge (natural things are mapped to the soul according to their form);

(b) and the object was nature itself, then it referred to the activity of producing itself (e.g., an organism is produced by nature);

(3) if, finally, god(s) took the role of the subject, then the activity was

(a) teaching and instructing in the case of man as object

(b) and shaping in the case of nature as object (giving form to substance).

Accordingly, the corresponding noun “informatio” had two different fundamental meanings:

(1) that of the activity of giving form to something/someone, and

(2) that of the result of this activity – being given form by something/ someone.

Note that meaning (2b) is an astonishingly modern-sounding notion. If we view humans as part of nature and assume that no god intervenes in natural processes, then this notion anticipates the very concept of selforganisation of today.

The whole variety of different meanings presented so far have one thing in common: in-forming means a process whose result is the emergence of something new.

At the dawn of the Industrial Age, the information concept spread from the Latin language into national languages and assumed an everyday content that did not cover all medieval meanings. With respect to pedagogy, the humanistic aspect of information as the education and development of human personality for the good and beautiful was set aside by the advent of modern philosophy. The rationalistic aspect of information was stressed as the intellectual process of communicating knowledge. In law, the information concept was at that time used to signify investigations.

The above developments cleared the way for the ultimate narrowing of the concept’s meaning from signifying the process of communication or investigation to the exclusive signification of what is being communicated or investigated. This truncation of the information concept was executed with the help of Shannon’s findings and writings. It reduced “information”, finally, to signify everything that is transmittable via communication technology. This led to the situation that “information” began to be used to designate something that, originally, in ancient Greece, was named “aggelia”, which is “message”. This had had a celestial origin and had been communicated by messengers and “angels” down to the humans on earth. It has now undergone secularisation, referring to the horizontal exchange between humans, moreover between humans and machines and even among machines.

The restriction of the information concept (along with its reification, i.e. the belief that it represents a kind of thing: the easiest way to imagine that which is being communicated is that it represents a thing) was key to its triumphal diffusion into literally all fields and disciplines in the decades after Shannon.

That development, however, has been losing momentum.

1.1.2 At the chaos point

Today, the use of the term of information seems to have reached its climax. At the same time, with each step in the narrowing interpretation of the term, its meaning seems to become more dubious. The end of this trend of usage and meanings of the information concept might mark a turning point. This condensation could not have progressed much further. At this point of time we are witnessing an apparent increase of attempts to complement or overcome the channel concept.

1.1.2.1 Disciplinary attempts

Numerous criticisms have been levelled at the Shannon type of “information”. That type has grown out of deliberations of single disciplines and points to particular problems. These problems mainly involve issues of how meaning enters the stage of information (a semantic question) and of how systems respond to information input (a pragmatic question).

The semantic information concept

The shortcomings of the new, narrow information concept were soon detected, with Donald M. MacKay being among the first to do so. Along with Shannon, he was invited to meetings in the legendary Macy Conferences series, which were famed for giving rise to cybernetics, system theory, and information theory. The eighth conference in March 1951 in New York City had “information as semantic” on the agenda. N. Katherine Hayles [1999, p. 74] reports that MacKay did not see

too close a connection between the notion of information as we use it in communications engineering and what [we] are doing here…the problem here is not so much finding the best encoding of symbols …but, rather, the determination of the semantic question of what to send and to whom to send it.

MacKay critiqued Shannon’s equation of information and the signals transmitted and proposed, instead, to define information as

the change in a receiver’s mindset, and thus with meaning

[Hayles 1999, p. 74]. Notwithstanding, Shannon’s notion prevailed because it could be mathematicised while, at first sight, MacKay’s could not. Shannon’s elaboration of the information concept achieved the status of “Information Theory”. Interestingly, as Robert K. Logan [forthcoming] annotates, it was MacKay who is cited in the Oxford English Dictionary as being the first to use the term in a heading in an article he published in the March 1950 issue of the Philosophical Magazine., Shannon’s theory, in contrast, could best be described as a mathematical theory of signal transmission.

MacKay’s insistence on including the meaning was not in vain. Another irony of history is that Gregory Bateson, one of the core group members of the Macy Conferences, anthropologist and cybernetician, has gained fame for his definition of information as “a difference which makes a difference” [1972, p. 453], while in the scientific community MacKay is credited with having defined information some years earlier in almost the same manner as “a distinction that makes a difference” (albeit without quote)b.

Another early attempt at including semantics was undertaken by Yehoshua Bar-Hillel and Rudolf Carnap [1953], who unsuccessfully tried to develop a logical calculus. This line of thought was followed by Hintikka (see [Hintikka and Suppes 1970]) and Dretske [1981] and is still being pursued, e.g. by Luciano Floridi [2003, 2004, 2005].

The pragmatic information concept

Warren Weaver [1949], when writing an introduction to Shannon’s ideas and admitting that Shannonian information was not about semantics, already gave the following classification:

(1) there are technical problems concerning the quantification of information that are dealt with by Shannon’s theory,

(2) there are semantic problems relating to meaning and truth,

(3) and there are what he thought to be “influential” problems that address the impact and effectiveness of information on human behaviour, which he thought had to play an equally important role.

This classification precisely describes what can be labelled the concept of “syntactic”, “semantic” and “pragmatic” information, respectively.

The pragmatic information concept has been coined by Ernst Ulrich von Weizsäcker [1986] and his wife Christine von Weizsäcker “as if the receiver mattered”: it is the receiver on which information has an impact; and it is the receiver who creates information. Information is said to be that which produces information. Different concepts have been developed, such as the trade-off between surprise and redundancy, intelligibility, context dependence, wholeness [Gernert 1996]. Klaus Kornwachs is one of the advocates and representatives of the pragmatic information concept today. This view is relevant for decision-making processes. Nonetheless, this view, which resembles behaviouristic blackbox models when relating the input of a system to its output, raises questions about whether the reified concept has really been broken up.

1.1.2.2 Transdisciplinary attempts

Besides the attempts to complement the Shannon information concept from a particular point of view, there has been a search for a concept that can overcome the shortcomings by integrating the various aspects of information processes. The useful aspects, if any, of the Shannonian term should be included as a special case, when extending the restricted information theory into a new, universal theory.

Clearly, transdisciplinary undertakings that strive for the bigger picture tend to be affiliated to philosophy, like – from different angles – the works of Rafael Capurro, Luciano Floridi or Kun Wu, and crossdisciplines such as cybernetics, system theory, evolutionary theory. Unsurprisingly then, a precursor of this line of thinking was developed from a philosophical perspective on cybernetics and system theory – by the French philosopher and sociologist Edgar Morin. Already in 1977, Morin developed a concept of information that defines information as that which is functional for the maintenance of a system. Only the first volume of his six-volume oeuvre La Méthode was translated into English (The Nature of Nature) [1992]; the German translation followed in 2010.

Conceptualisations which date from the second half of the 1980s mark a new period. These are:

(1) the hypothesis of the control revolution, which James R. Beniger [1986] uses to draw parallels between the breakthrough to the information society and former revolutions ...