Management Of Service Businesses In Japan

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Management Of Service Businesses In Japan

About this book

With the service industry taking up the largest portion of its GDP, Japan has much to share in the area of managing service industry. This book explores and elucidates the unique management styles in non-manufacturing industries or service industries in contemporary Japan, both practically and theoretically through case studies. These specially selected cases are the management of the world No.1 convenience store chain of Seven-Eleven, the sales finance business and auto sales business of Toyota, application of TPS (Toyota Production System) to life insurance company, performance evaluation of local government, BSC (balance scorecard) in local government hospitals, cost and pricing policy of telecommunication company, Japanese-style “hospitality” in the retail industry, service level agreement (SLA) in IT and shared service companies, and ICT (Information & Communication Technology) applied to BPN (Business Process Network) of service industry.

The analyses presented in this book were carefully laid out in regard to the business in general. It will be useful for business practitioners in service industry and beneficial to the scholars, students or general readers interested in this area.

Contents:

- Advanced Service Management in the Service Industries:

- Profit Sharing that Motivates Inter-Firm Cooperation within a Convenience Store Chain (Yasuhiro Monden and Noriko Hoshi)

- Profit Management in the Hotel Industry (Akimichi Aoki)

- Kaizen Activities and Performance Management in the Sales Finance Business (Noriyuki Imai)

- Performance Management in the Auto Sales Business (Noriyuki Imai)

- Productivity Improvement of Service Business Based on the Human Resource Development: Application of Toyota Production System to the Insurance Firm (Shino Hiiragi)

- Enacting Entrepreneurial Process on Family Business — Case of Health Care Business (Dun-Hou Tsai, Anders W Johansson and Shang-Jen Li)

- Advanced Service Management in the Public and Non-Profit Organizations:

- Performance Management Systems of Japanese Local Governments (Takami Matsuo)

- Implementation of the Balanced Scorecard in the Japanese Prefectural Hospitals (Naoya Yamaguchi)

- Pricing Policy and Potential Cost Reduction in Telecommunications (Manabu Takano)

- General Concepts and Techniques Applied to the Service Management:

- Omotenashi: Japanese Hospitality as the Global Standard (Nobuhiro Ikeda)

- The Service Level Agreements at Japanese Companies and Its Expansion (Tomoaki Sonoda)

- Application of Information and Communication Technology to the Service Industry — Focus on Business Process Network (Yoshiyuki Nagasaka and Gunyung Lee)

Readership: Researchers, graduates and undergraduates in business management, MBA, and service management courses; General public interested in the service industry; Professionals in marketing, service management and managerial accounting.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

in the Service Industries

Inter-Firm Cooperation within

a Convenience Store Chain

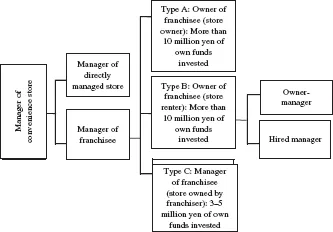

- (1) Differences in terms, when investing in or leasing store property

- (2) Differences in royalty rates, from company to company

- (3) Sharing the risk of disposal loss

- (4) Differences in franchise fees, from company to company

- (5) Sharing the risk of profit-earning among stores

- (6) Sharing the cost for interior finishing work

- (7) Sharing the cost of utilities

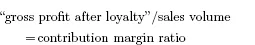

and Break-Even Point

the Cost of Disposal Loss, and Sharing the Risk

of Disposal Loss

the full disposal loss socially just?

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Subtitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Subtitle1

- Subtitle2

- Contents

- Preface

- About the Editors

- List of Contributors

- PART 1: Advanced Service Management in the Service Industries

- 1. Profit Sharing that Motivates Inter-Firm Cooperation within a Convenience Store Chain

- 2. Profit Management in the Hotel Industry

- 3. Kaizen Activities and Performance Management in the Sales Finance Business

- 4. Performance Management in the Auto Sales Business

- 5. Productivity Improvement of Service Business Based on the Human Resource Development: Application of Toyota Production System to the Insurance Firm

- 6. Enacting Entrepreneurial Process on Family Business — Case of Health Care Business

- PART 2: Advanced Service Management in the Public and Non-Profit Organizations

- 7. Performance Management Systems of Japanese Local Governments

- 8. Implementation of the Balanced Scorecard in the Japanese Prefectural Hospitals

- 9. Pricing Policy and Potential Cost Reduction in Telecommunications

- PART 3: General Concepts and Techniques Applied to the Service Management

- 10. Omotenashi: Japanese Hospitality as the Global Standard

- 11. The Service Level Agreements at Japanese Companies and Its Expansion

- 12. Application of Information and Communication Technology to the Service Industry — Focus on Business Process Network

- Index