![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 What are Plasmon Resonances?

The purpose of this introductory chapter is to discuss the physical origin of plasmon resonances in metallic nanoparticles, to describe their basic properties and to outline the approach to the study of plasmon resonances adopted in this book. The presentation in this chapter is mostly descriptive and avoids as much as possible mathematical technicalities which are provided in the subsequent chapters.

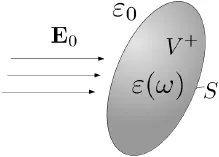

To start the discussion, consider a macroscopic piece of metal (gold or silver, for instance) subject to optical radiation (see Figure 1.1). In this situation, no unique physical phenomena of distinction or long remembrance occur; this macroscopic piece of metal is “lifeless.” However, if the dimensions of this metallic piece are made smaller and smaller and are eventually reduced to nanoscale, the resulting metallic nanoparticle may come to life while being subject to optical radiation. It may glow, it may resonate and it may become a very powerful, nanoscale localized source of light. This is, in descriptive terms, the essence of the phenomena of plasmon resonances in metallic nanoparticles. These powerful localized sources of light are useful in different areas of science and technology which include scanning near-field optical microscopy [1, 2], nano-lithography [3], biosensor applications [4, 5], surface enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) [6][9][8][9], nanophotonics [10][11][12][13], optical and magnetic data storage [14, 15], etc.

The question can be immediately asked: “What is the physical mechanism of plasmon resonances?” In other words: “What is there to resonate?” Experiments show that metallic (gold and silver) nanoparticles may exhibit resonance behavior at certain frequencies at which the following two conditions are satisfied: 1) the nanoparticle dielectric permittivity is negative and 2) the free-space wavelength is large in comparison with the nanoparticle dimensions. The latter condition clearly suggests that these resonances are electrostatic in nature. When dielectric permittivity is negative, the uniqueness theorem of electrostatics is not valid. For this reason, source-free electrostatic fields may appear for certain negative values of dielectric permittivity. This is the manifestation of resonances, and the corresponding source-free electrostatic fields are resonant plasmon modes.

Figure 1.1

It is important to stress that plasmon resonances in metallic nanoparticles are intrinsically nanoscale phenomena. This is because the two resonance conditions (negative dielectric permittivity and smallness of the particle dimensions in comparison with free-space wavelength) can be simultaneously and naturally realized at the nanoscale.

The question can be asked why it is possible and relevant to speak of dielectric permittivity of metallic nanoparticles subject to optical radiation. The reason is that conduction electrons in metallic nanoparticles are pinned by optical radiation and execute tiny back-and-forth oscillations around some “equilibrium” positions. In this sense, these conduction electrons are indistinguishable from bound charges in dielectrics. That is why metallic nanoparticles behave at optical frequencies as dielectric particles with dispersion. The latter means that dielectric permittivity depends on frequency. It turns out that for a certain frequency range its real part may assume negative values. As discussed later in this chapter, this frequency range for metals is near their plasma frequencies, where the dispersion relations ε(ω) are fully governed by the interaction between electromagnetic radiation (light) and the conduction electrons. For good conductors such as silver and gold, plasma frequencies are in the visible frequency range, and this explains why silver and gold nanoparticles are usually employed in plasmon resonance studies and applications. It is worthwhile to remark that plasmon resonances may occur not only in metallic nanoparticles but in any nanoparticle whose permittivity exhibits dispersion and whose real part may assume negative values. One example is the silicon carbide (SiC) material whose negative permittivity is not due to the interaction of conduction electrons with light but rather due to specific properties of lattice vibrations in polar crystals.

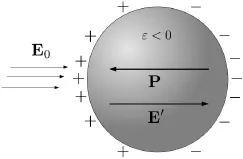

Figure 1.2

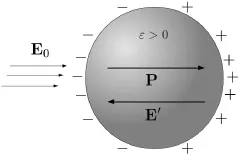

It has been already mentioned that the second condition of smallness of particle dimensions in comparison with free-space wavelength reveals the physical nature of plasmon resonances in nanoparticles as electrostatic resonances. Indeed, due to this condition, time-harmonic electromagnetic fields within the nanoparticles and in their vicinity vary almost with the same phase. As a result, at any fixed instant of time these fields look like electrostatic fields. The electrostatic nature of plasmon resonances in nanoparticles and their occurrence for negative values of dielectric permittivity immediately suggest the enhancement of local electric fields inside nanoparticles and their vicinities. To illustrate this fact, consider an example of a spherical nanoparticle with negative permittivity ε subject to uniform external field E0 (see Figure 1.2). Since ε < 0, the polarization vector P has the direction opposite to E0 and this results in surface electric charges which create the “depolarizing” field E′ with the same direction as E0. This naturally leads to the enhancement of the total electric field E = E0 + E′ inside the spherical nanoparticle *. To better appreciate this fact, it is instructive to consider the case of a spherical nanoparticle with positive permittivity (Figure 1.3) where the depolarizing field E' results in the attenuation of the external field E0.

Figure 1.3

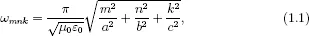

In our study of plasmon resonances in nanoparticles, we shall follow the traditional approach when all losses are first neglected and resonance modes and resonance frequencies are first found for lossless systems. A similar approach is used, for instance, in the study of resonance modes in metallic cavities. For such cavities, the resonance mode problem is mathematically formulated as an eigenvalue problem for specific differential equations derived from the Maxwell equations. It will be demonstrated in this book that the problem of plasmon resonance modes can be also mathematically formulated as an eigenvalue problem which is posed, however, not for differential equations but rather for specific boundary integral equations. There is another important difference between plasmon resonances in metallic nanoparticles and resonances in metallic cavities. In the latter case, the resonance frequencies depend on the shape and dimensions of the metallic cavities. For instance, in the case of rectangular resonant cavities (see Figure 1.4), the resonance frequencies are given by the formula

Figure 1.4

which clearly reveals their dependence on cavity dimensions a, b and c. It will be demonstrated in this book that in the case of plasmon resonances in metallic nanoparticles, resonance frequencies are scale-invariant. This means that these frequencies depend only on particle shapes but not on their dimensions, provided that these dimensions are appreciably smaller than resonance free-space wavelengths. This scale invariance implies, among other things, that in the case of ensembles of almost self-similar (of the same shape but different dimensions) metallic nanoparticles, they may resonate at practically the same wavelength. Consequently, plasmon resonances can be simultaneously excited in all these nanoparticles.

It turns out that the eigenvalue formulation of the plasmon resonance problem has another important feature. This eigenvalue formulation leads to the direct calculation of the negative values of dielectric permittivity at which plasmon resonances may occur. These negative values of dielectric permittivity can then be used for any dispersion relation of nanoparticle to determine the corresponding resonance frequencies. In this way, the properties of plasmon resonances which depend on nanoparticle shapes can be fully separated from those which depend on the material properties of nanoparticles which define their dispersion relations. In other words, the solution of the plasmon resonance eigenvalue problem for a nanoparticle of specific shape can be used for different materials of this nanoparticle to find resonance frequencies.

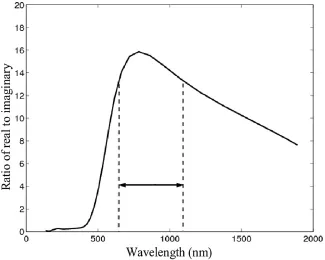

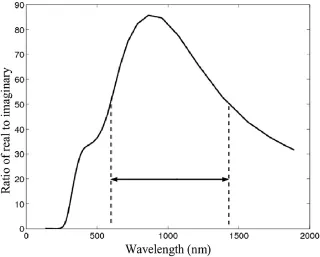

Having found plasmon resonance modes and their resonance frequencies for lossless metallic nanoparticles through the solutions of the appropriate eigenvalue problem, the next step is to study the excitation of these plasmon modes by the incident radiation and the effect of ohmic and radiation losses. This approach is adopted in the book and it reveals that, by and large, dipole plasmon modes are excited by incident optical radiation created by remote sources. This is because the electric field of this radiation is practically uniform over the nanoparticle region due to the smallness of nanoparticle dimensions in comparison with the wavelength of the incident radiation. It also turns out that the incident radiation is most efficiently coupled to a plasmon mode if the dipole moment of this mode is parallel to the direction of electric field of the incident radiation. The plasmon mode excitation analysis also reveals that the quality of plasmon resonances, i.e., the local enhancement of the incident optical radiation, is controlled by the ratio of the real part of dielectric permittivity to its imaginary part at the resonance frequency. For gold and silver, this ratio is most appreciable when the free-space wavelength is within the ranges of 650-1000 nm and 600-1400 nm (see Figures 1.5 and 1.6, respectively, which are based on experimental data of P. B. Johnson and R. W. Christy [16]). Therefore, plasmon resonances in gold and silver nanoparticles can be most efficiently excited in the corresponding frequency ranges. It is also worthwhile to observe that the ratio of real and imaginary parts of dielectric permittivity is appreciably higher for silver than for gold. Thus, as far as the quality of plasmon resonances is concerned, silver is “gold” and gold is “silver.” This fact has long been appreciated in the area of surface enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) research where silver nanoparticles have been predominantly used in experiments. Of course, silver oxidation presents some experimental difficulties that must be dealt with.

Figure 1.5

Figure 1.6

1.2 Dispersion Relations

It is clear from the presented discussion that the dispersion relation ε(ω) of a metallic nanoparticle is instrumental for the analysis of plasmon resonances. For this reason, it is worthwhile to briefly review the simplest analytical models for the dispersion relations. We start with the case of the free-electron plas...