![]()

1

Introduction

CONTENTS

1.1 Overview of Research and Development Processes

1.2 Questions

1.1 Overview of Research and Development Processes

Medical research is the iterative search for the understanding of the human body based on a scientific process. Such pure research seeks for the truth without a predefined utility at the start, whereas applied research that pertains to the development of biomedical devices seeks to solve medical related problems with the motivation of addressing the patient (or consumer) needs. Devices arising from applied research can be used to support pure research. For instance, the developed biomedical devices such as medical image scanners can be used to examine the human body physiologically and conduct medical research. This book focuses on the science of research and development of biomedical devices. In recent decades, the advancement of medical imaging, computer technology and manufacturing processes have added value the conceptualisation and development of new biomedical applications, and significantly improved health and living standards as well as contributing to medical science and technology.

An example of a biomedical device may be a surgical assisting application, or a mechanism of delivering drug into the human body. The purpose of using such a device is to provide specific medical assistance and long-term safety while minimising the device-related complications. The presentation of a systematic framework addresses the development of a biomedical device to meet health standards or safety limits by showing the integration of the required processes and instruments used in its design, evaluation, prototyping and delivery. In this book, we introduce the outline of devising and testing some selected biomedical devices as well as to highlight the nature of their applications and impact to the medical industry.

There has been a rapid introduction of computational modelling tools, medical imaging, optical-based flow measurements, sensor technology and manufacturing processes into the development of a biomedical device. This has resulted in the implementation of the device from the start of its conceptualisation to prototyping and testing to become an engineering challenge and requires detailed management and analysis at every stage of its development.

The first stage of biomedical device development is design realisation and innovation. Design rules based on certain specifications defined along the process of realising the product can be achieved with reference to a set of product operation and safety guidelines. Two types of design innovation exists: autonomous – design realisation independent from its other existing innovations, whereby a new design rule to increase the effectiveness of the device or its level of safety can be developed without redesign of the entire product; and systemic – design realisation in conjunction with its related complementary innovations, whereby new design updates requires the need to reformulate the old design rules and redefine the design of the product. Coordinating an autonomous or systemic design product innovation is particularly difficult when dealing with many design options. Therefore, computational modelling and design based on computer-aided design packas can help to lower product development cost significantly. Alternatively or as a complement platform, rapid prototyping based on stereolithography1 can also assist biomedical engineer in visualising their products or to be utilised during experimental testing.

The next stage is the visualisation of the product performance, which can be computational or mechanical simulation, and in some cases, based on clinical imaging. Computational tools such as computer-aided design (CAD) software, numerical solvers for computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and flow visualisation packages are mainly used in simulation, visualisation and verification stages of the development. Medical imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) can produce images of anatomical or functional features in vivo. These images can be processed and reconstructed to provide useful information for visualisation using computer modelling tools. Medical imaging is well known for its ability to present the anatomical scenario within the human body so that identification of locations for device implants, drug delivery or rectification of anatomical defects may be examined.

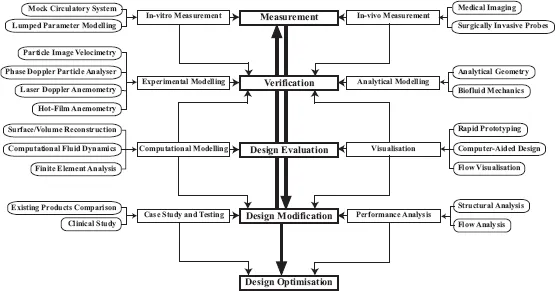

As mentioned, the evaluation of the device performance may be experimental, computational and clinical. Figure 1.1 depicts the different computational and mechanical instruments in the development cycle of a biomedical device that play specific roles. Experimental simulations using particle image velocimetry (PIV) and laser Doppler measurements have been able to derive fluid mechanical properties of flow through mechanical devices, such as the prosthetic heart valves and stents, before actual implantation into the human body. Such experimental information may often be complemented by CFD simulation for cross-checking. In some cases, it may be possible to retrieve in-vivo functional measurements for clinical verification. For example, phase contrast MRI may be used to present flow maps of the cardiac circulation in the heart and compare against those that are simulated.

FIGURE 1.1

Stages for developing a biomedical device. The success of a biomedical device involves various stages in its design evaluation and testing from the structural and flow perspective. The anatomical and functional characteristics of the pathology prior and post surgical implantation of a biomechanical structure can be examined for its effectiveness. The simulation of drug delivery process based on various mechanical parameters can assist in improving the device design. These testing and remodelling processes involve the system integration of various technical developmental procedures, which can be computational or experimental.

We examine the design and measurement, prototyping, testing, evaluation and proposal for delivery of a biomedical device from the system engineering perspective. Some of these processes may be performed on the mechanical or computation platform. In the generic sense, the terminology measurement refers to the physical scanning of parameters in the system evaluation of the device. The term computational means numerical calculations with the aid of a computerised system while mechanical relates to the physical extraction of data or modelling of a hard-copy prototype in terms of biomedical product development.

Ideally, in-vivo medical imaging and in-vitro measurement devices may be used for modelling of the actual device performance before and after its implantation depending on the availability and permission for experimentation of the test subject. However, this may sometimes be limited by the ability to measure the device in operation due to technological constraint. For example, nuclear signals from metallic device show up as void in MRIs.2 In-vivo measurements give a perspective of the realistic impact that the biomedical device can have on the anatomical functions whereas in-vitro measurements, often used in experimental verification of the device, are based on a mechanically confined environment where the parameters of the anatomical events may be simulated or the introduction of the measurement sensors may affect the performance of the device in situ. Computational modelling may sometimes supplement the measured data as a form of cross-check. As such, measurements together with the computational modelling can provide a strong examination of the biomedical operations with the relevant anatomical functional behaviour.

Visualisation is important after the measurement process. Collected data needs to be processed and presented in useful formats to the user. For example, the geometrical determination of cardiovascular or respiratory structures by medical imaging or scanning in two dimensions (2D) needs to be reconstructed in a computational platform for three-dimensional (3D) visualisation. This can assist in the evaluation of design and also facilitate the simulation of device performance computationally once the anatomical environment is known more clearly. With the rapid development of medical imaging techniques and visualisation tools, 3D reconstructions offer additional information when compared to planar axial images. For example, in pre- and post-endovascular stent grafting, it has become a routine clinical tool in both surgical planning and post-operative follow up.3,4 This is especially demonstrated by virtual intravascular endoscopy (VIE) visualisation that can allow an accurate assessment of the treatment outcomes of endovascular aortic stents in terms of the intraluminal appearances and stent position or protrusion.

Experimental flow mapping may be broadly classified with the following main characteristics and nature: optical, magnetic resonance or ultrasonic-based velocime-try systems.5 PIV is an example of an experimental optical velocimetry system used to verify design performance. The design of a device or structure can be investigated experimentally using a physical model which is interrogated using techniques

such as PIV performance.6,7

Velocity-encoded medical imaging such as phase contrast MRI can be used to generate 2D flow maps. Of recent advancement is the phase contrast MRI that is able to map flow fields of up to 3D in vivo.8– 10 Two-dimensional ultrasonic flow field mapping has been able to enable useful results in cardiac diagnosis,11 and can potentially be developed into an experimental flow imaging system for biomedical device evaluation.

Finite element analysis (FEA) is another category of computational simulation that is able to evaluate structural performance of the device. Considering the ability to model more advanced geometries, FEA has become a popular computational numerical method, oppose to theoretical or analytical modelling. Various researchers have utilised advanced FEA techniques for modelling and analysis of implantable devices for applications such as drug delivery systems,12,13 artificial organs14–17 and endovascular stents.4

CFD is a numerical method that can be used to provide detailed flow information in the human that cannot easily be provided by experiment.18– 22 Furthermore, CFD and FEA techniques complement results to experiments. Once validated, the model can be used to investigate the effects of changing parameters or geometry with greater certainty, and at substantially less cost than building a new experimental prototype. In addition, the simulation of design performance can be achieved to evaluate the safety of the device implant or the effect of introducing drugs into a system without endangering human lives. It may serve to provide expert opinion to surgeons in the event of strategising the device implant through better understanding of its operating mechanism.

During design evaluation, existing biomedical device products are compared and calibrated against the proposed design in terms of performance. In this analysis, statistical studies based on device testing on a population of human subjects are an important criterion in commissioning the product. The flow performance of the device is also another consideration as improved operation of the product will enable better marketability. Products often need to be designed and re-designed again based on the vigorous testing and evaluation procedures.

In summary, in order to sufficiently evaluate the design of a biomedical device such that we are ...