Handbook On Social Stratification In The Bric Countries: Change And Perspective

Change and Perspective

- 856 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Handbook On Social Stratification In The Bric Countries: Change And Perspective

Change and Perspective

About this book

Along with the fast growing economy, the term “BRICs” was coined to represent the newly emerging countries — Brazil, Russia, India and China. The enhanced economy in these countries has largely improved people's life; at the same time, it has also strongly influenced the transformation of social structure, norms and values. However, as the world's attention centers on their economic development at the micro level, the social changes at the micro level have often been neglected, and a specific comparative study of these four countries is even more rare.

This handbook's contributing authors are leading sociologists in the four countries. They fill the gap in existing literature and examine specifically the changes in each society from the perspective of social stratification, with topics covering the main social classes, the inequality of education and income, and the different styles of consumption as well as the class consciousness and values. Under every topic, it gathers articles from authors of each country. Such a comparative study could not only help us achieve a better understanding of the economic growth and social development in these countries, but also lead us to unveil the mystery of how these emerging powers with dramatic differences in history, geography, culture, language, religion and politics could share a common will and take joint action. In general, the handbook takes a unique perspective to show readers that it is the profound social structural changes in these countries that determine their future, and to a large extent, will shape the socio-economic landscape of the future world.

Contents:

- Changes in Social Stratification:

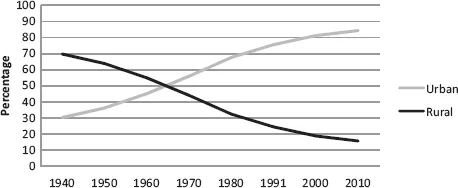

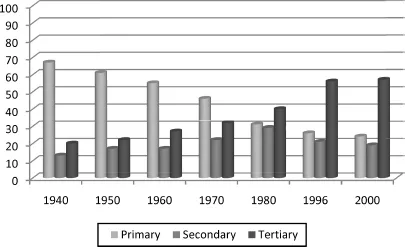

- Social Stratification and Its Transformation in Brazil (C Scalon)

- Changes in the Social Structure of Russian Society Within a Period of Transformation (Z T Golenkova and M K Gorshkov)

- Social Stratification and Change in Contemporary India (K L Sharma)

- Changes in China's Social Stratification Since 1978 (Li Peilin)

- The Working Class:

- Labor, Workers, and Politics in Contemporary Brazil: 1980–2010 (M A Santana)

- The Working Class in a Transitional Society: From the Soviet Union to the Russian Republic (Z T Golenkova and E D Igitkhanian)

- The Urban Industrial Working Class and the Rural Peasant Working Class in India (K L Sharma)

- The Status Quo and Change to the Working Class in Contemporary China (Li Wei and Tian Feng)

- Peasants:

- The Brazilian Peasantry: A History of Resistance (M de Nazareth Baudel Wanderley)

- The Transformation of the Social Structure in Modern Rural Russia (A A Hagurov)

- The Differentiation of the Peasantry in India Since Independence (K L Sharma)

- Rural Society and Peasants in China (Fan Ping)

- Enterprises and Entrepreneurship:

- Innovative Entrepreneurship in Brazil (S K Guimarães)

- The Development of Entrepreneurship in Russia: Main Trends and the Status Quo (A Chepurenko)

- Tradition and Entrepreneurship of Indian Private Entrepreneurs (K L Sharma)

- China's Fledgling Private Entrepreneurs in a Transitional Economy (Chen Guangjin)

- The Middle Class:

- The Formation of the Middle Class in Brazil: History and Prospects (A Salata and C Scalon)

- The Middle Class in Russian Society: Homogeneity or Heterogeneity? (N E Tichonova and S V Mareyeva)

- The Rise of the Middle Class in India Since Independence (K L Sharma)

- The Heterogeneous Composition and Multiple Identities of China's Middle Class (Li Chunling)

- Income Inequality:

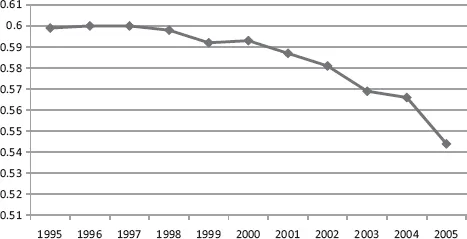

- Income Inequality and Social Stratification in Brazil: Key Determining Factors and Changes in the First Decade of the 21st Century (L G Costa and C Scalon)

- Income Inequality in Russia (Y Epikhina)

- Poverty and Income Inequality in India's Urban and Rural Areas (K L Sharma)

- Structural Characteristics and Trends of Income Inequality in China (Chen Guangjin)

- Educational Inequality:

- Educational Inequality and Social Stratification in Brazil (M da Costa, M C Koslinski and L G Costa)

- Inequality in Education: The Case of Russia (D L Konstantinovskiy)

- Education and Social Stratification in India: Systematic Inequality (K L Sharma)

- Educational Inequality and Educational Expansion in China (Li Chunling)

- Consumption:

- Beyond Social Stratification: A New Angle on Consumer Practices in Contemporary Brazil (M Castañeda)

- Consumption and Lifestyle in Russia (P M Kozyreva, A E Nizamova and A I Smirnov)

- The New Emerging Consumption Class and Their Lifestyles (K L Sharma)

- The Stratification of Consumption Among Social Classes, Occupational Groups, and Identity Groups in China (Tian Feng)

- Class Consciousness and Values:

- Working Class Formation in Brazil: From Unions to State Power (A Cardoso)

- The Research of Class and Group Consciousness in Contemporary Russian Society (M F Chernysh)

- Social-Class Connection and Class Identity in Urban and Rural Areas (K L Sharma)

- Stratum Consciousness and Stratum Identification in China (Li Wei)

Readership: Academics, professionals, graduates and undergraduates interested in sociology, social structure and social issues in the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China).

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Title Page1

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- List of Contributors

- Part One: Changes in Social Stratification

- 1. Social Stratification and Its Transformation in Brazil

- 2. Changes in the Social Structure of Russian Society Within a Period of Transformation

- 3. Social Stratification and Change in Contemporary India

- 4. Changes in China’s Social Stratification Since 1978

- Part Two: The Working Class

- 5. Labor, Workers, and Politics in Contemporary Brazil: 1980-2010

- 6. The Working Class in a Transitional Society: From the Soviet Union to the Russian Republic

- 7. The Urban Industrial Working Class and the Rural Peasant Working Class in India

- 8. The Status Quo and Change to the Working Class in Contemporary China

- Part Three: Peasants

- 9. The Brazilian Peasantry: A History of Resistance

- 10. The Transformation of the Social Structure in Modern Rural Russia

- 11. The Differentiation of the Peasantry in India since Independence

- 12. Rural Society and Peasants in China

- Part Four: Enterprises and Entrepreneurship

- 13. Innovative Entrepreneurship in Brazil

- 14. The Development of Entrepreneurship in Russia: Main Trends and the Status Quo

- 15. Tradition and Entrepreneurship of Indian Private Entrepreneurs

- 16. China’s Fledgling Private Entrepreneurs in a Transitional Economy

- Part Five: The Middle Class

- 17. The Formation of the Middle Class in Brazil History and Prospects

- 18. The Middle Class in Russian Society: Homogeneity or Heterogeneity?

- 19. The Rise of the Middle Class in India since Independence

- 20. The Heterogeneous Composition and Multiple Identities of China’s Middle Class

- Part Six: Income Inequality

- 21. Income Inequality and Social Stratification in Brazil: Key Determining Factors and Changes in the First Decade of the 21st Century

- 22. Income Inequality in Russia

- 23. Poverty and Income Inequality in India’s Urban and Rural Areas

- 24. Structural Characteristics and Trends of Income Inequality in China

- Part Seven: Educational Inequality

- 25. Educational Inequality and Social Stratification in Brazil

- 26. Inequality in Education: The Case of Russia

- 27. Education and Social Stratification in India: Systematic Inequality

- 28. Educational Inequality and Educational Expansion in China

- Part Eight: Consumption

- 29. Beyond Social Stratification: A New Angle on Consumer Practices in Contemporary Brazil

- 30. Consumption and Lifestyle in Russia

- 31. The New Emerging Consumption Class and Their Lifestyles

- 32. The Stratification of Consumption among Social Classes, Occupational Groups, and Identity Groups in China

- Part Nine: Class Consciousness and Values

- 33. Working Class Formation in Brazil: From Unions to State Power

- 34. The Research of Class and Group Consciousness in Contemporary Russian Society

- 35. Social-Class Connection and Class Identity in Urban and Rural Areas

- 36. Stratum Consciousness and Stratum Identification in China

- List of Tables and Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- References

- Index