![]()

Chapter 1

Value Solutions for Superadditive Transferable Utility Games in Coalition Function Form

Game theory has two major subdivisions: noncooperative and cooperative game theory. In noncooperative game theory, neither agreements to choose a joint strategy nor threats to retaliate or punish particular strategy choices are credible per se. That is, unless the threat or the terms of the agreement correspond to a subgame perfect Nash equilibrium, an agent who is rational in the sense of noncooperative game theory will not carry it out, and since this is commonly known, threats or agreement will have no impact on the actual decisions of the agents. In cooperative game theory, the assumption is instead that if an agreement is in the advantage of all those who are party to it, or if a threat can improve the payoffs to an agent, then rational beings will find ways to commit themselves to the agreement or the threat and enjoy the benefits that arise from the agreement or the credibility of the threat. The word “cooperative,” used in this way, has no normative content.1 Indeed, one possibility is that a group of agents may cooperate to exploit another agent or group of agents, as von Neumann stresses (1959, p. 33). This book will be concerned with cooperative games in this neutral sense.

There is a large literature on the topic. No attempt will be made to survey this literature as a whole. The purpose of this chapter is purely expository, and it will discuss some concepts that will be reconsidered and extended in the balance of the book. Section 1.1 will summarize the logical framework for a very large and important segment of the literature, the theory of superadditive transferable utility (TU) games in coalition function form. Section 1.2 will discuss the concept of the core, which is not central to the purposes of this book but is the most widely used solution concept for these games and an important background for the study reported in this book. The remaining sections will discuss two concepts of solution that have a valuable property: for any such game, they provide a unique determination of the value that each agent can reasonably expect to derive from her or his participation in the game, i.e., value solutions for games in this category.

1.1. Superadditive Games in Coalition Function Form

An agreement to choose a common strategy is conventionally called a coalition among the agents who are parties to the agreement. Any subset of the players in a game may constitute a coalition. A coalition of all players in the game is conventionally called the grand coalition. A coalition with only a single member is conventionally called a singleton coalition. Coalitions are usually considered to be non-null, but for some special purposes, it may be helpful to make reference to a null coalition, i.e., a coalition without members.

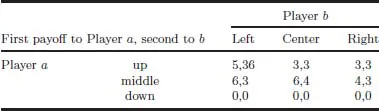

Noncooperative games may be represented in strategic normal or extensive (decision tree) form. Cooperative games are usually represented in a less detailed way, but the idea that the play of the game is the choice of a strategy, and in a cooperative game, a common strategy is always in the background. Accordingly, as a motivating example, consider the following game in strategic normal form2:

As we see, each player has three strategies. The unique Nash equilibrium occurs when the strategies played are (middle, center) and the payoffs are 6 and 4. At strategies (up, left), however, the payoff to Player b is nine times that at Nash equilibrium, while the payoff to Player a is only reduced by one-sixth relative to the Nash equilibrium. It seems that a shift from (middle, center) to (up, left) would make Player b better off by a big enough margin that he could compensate Player a for his sacrifice so that they both would be better off. The compensatory payment from b to a is called a side

Table 1.1. Game 1.1. A game in strategic normal form.

payment in game theory. This intuition is captured, in a strong and simple way, in a simplifying assumption widely used in cooperative game theory: transferable utility.

Assumption TU. In a coalition, the total payoffs to all players can be costlessly redistributed among the members of the coalition in any proportions.

Thus, having adopted Assumption TU, in case a coalition of Players a and b choose (up, left), the payoffs may be any pair that adds up to 41. Assumption TU rules out two kinds of complications. First, treating the payoffs as money payoffs, it may be that money is not equally a motivation to all players in all circumstances. The payoffs should be interpreted as utility payoffs, not as money payoffs, since otherwise in some circumstances rational players might not choose the largest payoff. But, second, there might be costs of making transfers, and particularly transfers in equal units of utility.3 Assumption TU assures us that the payoffs are indeed proportionate to utility, but also that transfers can be costlessly made in ways that preserve the constant total utility accruing to the coalition. Accordingly, for the grand coalition of all players (in this case of the two players a and b) we can identify the value of the coalition as the largest total payoff that the two can obtain with a common strategy: in this case a value of 41, on the condition that they choose the joint strategy (up, left).

But what is the value of the singleton coalitions {Player a} and {Player b}? For each player, this will depend on the strategies chosen by the other player. It might seem that this would identify the values at the Nash equilibrium, and, as we will see later in the book, this could be a reasonable definition for certain purposes, but it is not customary in the literature on cooperative games. For, recall, “if a threat can improve the payoffs to an agent, then rational beings will find ways to commit themselves to…the threat.” In Game 1.1, by choosing strategy (down), Player a can always reduce Player b to a payoff of zero. This will enhance Player a’s bargaining power (we suppose), so he will make the threat and, if there is no cooperative agreement, will carry it out even at the sacrifice of a positive payoff for himself. Therefore, the greatest payoff that Player b can assure himself of is zero, and this is the value of the singleton coalition {Player b}. But, conversely, by choosing strategy (middle), Player a can assure himself of at least 4, and ag...