Non-axiomatic Logic: A Model Of Intelligent Reasoning

A Model of Intelligent Reasoning

- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

This book provides a systematic and comprehensive description of Non-Axiomatic Logic, which is the result of the author's research for about three decades.

Non-Axiomatic Logic is designed to provide a uniform logical foundation for Artificial Intelligence, as well as an abstract description of the “laws of thought” followed by the human mind. Different from “mathematical” logic, where the focus is the regularity required when demonstrating mathematical conclusions, Non-Axiomatic Logic is an attempt to return to the original aim of logic, that is, to formulate the regularity in actual human thinking. To achieve this goal, the logic is designed under the assumption that the system has insufficient knowledge and resources with respect to the problems to be solved, so that the “logical conclusions” are only valid with respect to the available knowledge and resources. Reasoning processes according to this logic covers cognitive functions like learning, planning, decision making, problem solving, etc.

This book is written for researchers and students in Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Science, and can be used as a textbook for courses at graduate level, or upper-level undergraduate, on Non-Axiomatic Logic.

Contents:

- Introduction

- IL-1: Idealized Situation

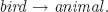

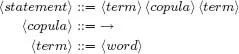

- NAL-1: Basic Syntax and Semantics

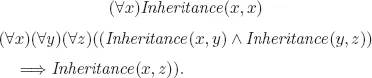

- NAL-1: Basic Inference Rules

- NARS: Basic Memory and Control

- NAL-2: Derivative Copulas

- NAL-3: Set-Theoretic Terms

- NAL-4: Relational Terms

- NAL-5: Statements as Terms

- NAL-6: Variable Terms

- NAL-7: Events as Statements

- NAL-8: Operations and Goals as Events

- NAL-9: Self-Monitoring and Self-Control

- Summary and Beyond

Readership: Students and professionals interested in the field of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- NON – AXIOMATIC LOGIC

- NON – AXIOMATIC LOGIC

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of Tables

- Introduction

- IL-1: Idealized Situation

- NAL-1: Basic Syntax and Semantics

- NAL-1: Basic Inference Rules

- NARS: Basic Memory and Control

- NAL-2: Derivative Copulas

- NAL-3: Set-Theoretic Terms

- NAL-4: Relational Terms

- NAL-5: Statements as Terms

- NAL-6: Variable Terms

- NAL-7: Events as Statements

- NAL-8: Operations and Goals as Events

- NAL-9: Self-Monitoring and Self-Control

- Summary and Beyond

- Narsese Grammar

- NAL Inference Rules

- NAL Truth-Value Functions

- Proofs of Theorems

- Bibliography

- Index