![]()

PART I

![]()

CHAPTER 1

KEY IDEAS IN BEHAVIOURAL ECONOMICS — AND WHAT THEY MEAN FOR POLICY DESIGN

KOH Tsin Yen

Introduction

A primary function of policymakers is to anticipate the impact of their policies and assess the likelihood that their policies will yield the desired outcomes. Will lowering income tax rates increase investment by firms and encourage more work by individuals, or will it leave firm and worker behaviour unchanged? Will raising road usage charges lead to a decline in the number of cars on the road or will it have no impact on driver behaviour? Will increasing maternity benefits result in an increase in fertility rates, or will it simply become deadweight funding for the state? At the heart of these and many other policy decisions are implicit assumptions and questions about the factors which drive human decisions and behaviour.

The dominant theory of decision making in economics and other social sciences has been the rational choice model. People are generally assumed to be self-interested, rational agents: they analyse the costs and benefits of various options and choose the option that maximises their utility. They have stable, consistent preferences and the options they face are comparable to one another. This model is also a common paradigm for analysing policy decisions. In choosing between various options, policymakers typically assume that people will respond rationally — and therefore predictably — to incentives. Consequently, the right policy is that which creates incentives for the desired behaviour.

In the last thirty years or so, behavioural economics has emerged as a way of introducing insights from psychology into economics. Behavioural economics starts from the observation, borne out by numerous experiments, that individuals often deviate from strict rationality in systematic ways, not just arbitrarily or occasionally. This field of economics seeks to introduce more robust and realistic descriptive models of decision making and choice into standard economic theory. The implications of behavioural economics have not been lost on policymakers, and attention to the field has grown in academic and policy communities.

Individuals often deviate from strict rationality in systematic ways, not just arbitrarily or occasionally.

This chapter will first describe how economic theory, and in particular the rational choice model, has been applied in Singapore's public policy context. It then explains the challenge behavioural economics poses to the rational choice model, finally concluding with the implications of behavioural economics for public policy, particularly in Singapore's context.

The Economic Foundations of Public Policy in Singapore

The Singapore government prides itself on its pragmatic and rational approach to public policy. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong once described Singaporean civil servants as “practis[ing] public administration almost in laboratory conditions”, referring to the environment that supports, “Singapore's ability to take a longer view, pursue rational policies, put in place the fundamentals which the country needs, and systematically change policies which are outdated or obsolete” (Lee 2005, p. 7). One manifestation of this rationality in government is in the application of economic principles to almost all areas of public policy.

There are at least three main ways in which this is done. The first and most obvious is in the use of incentives to shape or change behaviour. People and firms are assumed to respond rationally to incentives. Lowering corporate tax rates will lead to higher levels of private investment, raising road usage charges will lead to fewer cars on the road, and increasing maternity and other parenthood benefits will result in an increase in birth rates. Getting incentives right is arguably one of the most important considerations in the design and implementation of public policy in Singapore. For instance, while the government subsidises healthcare expenses, it also requires that users co-pay a share of their medical bills. The primary consideration behind this policy is the concern that free healthcare will erode the incentive for users to exercise prudence and economise in their healthcare consumption decisions. Co-payment is seen as necessary to align the incentives of the patient and the payer (in this case, the government), and limit people's propensity to over-consume publicly subsidised services.

Another area in which public policy decisions are motivated largely by the incentive effects they produce is in the design of welfare policy. Singapore has always resisted the introduction of a universal, needs-based welfare system because of the adverse incentive effects and moral hazard problems that such a system would generate. Raising the benefits of being unemployed, it is argued, would lower the cost of unemployment for the individual and result in more people choosing to remain unemployed. Instead, Singapore's approach is to “make work pay” through wage supplementation for low-wage workers.

The second way in which the Singapore government applies conventional economics in public policy is in the use of cost-benefit analysis. The rational choice model assumes that agents are able to generate a range of alternatives and to weigh the costs and benefits of each alternative before deciding on a course of action. As a theory of decision making for individuals, it has been criticised on both descriptive and normative grounds. As a theory of public decision making, however, it is not inaccurate. Cost-benefit analysis is an indispensable part of the Singapore policymaker's toolkit. Should the government build a new subway line? Should it finance the development of a high-speed fibre optic network? Will casinos bring greater benefits to Singapore than the social costs that might be created? No matter the policy domain, the policymaker is expected to generate a range of alternatives and make an objective assessment of the costs and benefits of the various alternatives, before arriving at a decision. Cost-benefit analysis, while imperfect and dependent on the assumptions made by policymakers, at least attempts to provide an objective basis on which to assess the relative merits of different options.

More broadly, the crux of policymaking lies in balancing and making trade-offs between competing values and priorities. Not all costs and benefits are easily quantifiable or commensurable — it is not immediately obvious, for example, how one might assess whether a plot of land should be set aside for a church, a school or an office building — but the process of cost-benefit analysis forces the policymaker to explicitly and deliberately consider the tradeoffs that need to be made and to attempt to put the competing demands on a common metric.

A third way in which standard microeconomic principles are applied in Singapore public policy is in the area of market liberalisation and regulation. This involves considerations such as the structure of the market that best promotes competition, the pace of liberalisation, and the regulation of any remaining monopoly power post-liberalisation. With a relatively small domestic market, economies of scale and scope make it likely that the outcome of liberalisation would be monopolies or oligopolies in areas such as the provision of potable water, the electricity grid and public transport. The overriding concern for regulators would then be to prevent firms or entities with monopolistic power from abusing their market power, while not eroding incentives for them to improve their performance.

In each of these examples, the principle of the Singapore government has been to work with incentives and make use of markets even when it accepts the need for some form of government intervention. Policies are designed to align or strengthen the incentives to produce particular outcomes, rather than to mandate outcomes.

Bounded Rationality, Bounded Self-Control, Bounded Self-Interest

The influence of neoclassical economics policymaking in Singapore has been significant but not exclusive. Experienced policymakers, whether in Singapore or elsewhere, know that people do not always act rationally or in a way consistent with their long-term interests. This could be for any number of reasons — they may not be able to assess the costs and benefits of various options accurately, or it may be too complicated for them to do so; they may not have the willpower or self-control to act in their own interests; they may make seemingly sub-optimal choices for reasons not adequately acknowledged by the rational choice model, such as altruism; or their decisions may be shaped by heuristics and cognitive biases. The reality is that policymakers have to consider how people actually make decisions — as opposed to how textbook economics assumes they will make decisions — when designing and implementing policies.

This is where the behavioural sciences have made a valuable contribution to our understanding of decision making. We can understand the development of behavioural economics and its acceptance into mainstream economics as book-ended by two Nobel Prizes in Economics, notable for their being awarded not to economists but to psychologists. The first Nobel Prize was given to Herbert Simon in 1978 for his work in developing the concept of bounded rationality. Simon argued that the theory of rational choice favoured by classical economic theory placed unrealistically high cognitive demands on people — it was simply not possible for individuals and firms to generate all possible alternatives, or to work out the consequences of the full range of alternatives, or even to adjudicate between competing wants (especially by equating costs and benefits at the margin). Instead, Simon proposed that a descriptive theory of decision making should replace the concept of utility maximisation. He called it “satisficing” — the notion that economic agents generated an aspiration of the kind of solution they were looking for, searched for it one solution at a time, and stopped searching once they had found something acceptably close to their aspiration. Aspirations were not static but could change as people accumulated experience (Simon 1979).

The second prize was awarded to the psychologist Daniel Kahneman in 2002. Kahneman and his main collaborator, the late Amos Tversky, built on Simon's work to draw “maps of bounded rationality” by exploring the differences between the choices people actually made under conditions of uncertainty and the choices predicted by the rational choice model (Kahneman 2002).

Each of the three lines explored by Kahneman and Tversky — heuristics and biases, prospect theory and loss aversion, and framing effects — has had significant implications for economics. For example, the idea that people are generally loss averse, a central proposition of prospect theory, has led to the exploration of what behavioural economists call the endowment effect, or the value we place on our possessions solely because they belong to us (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). The endowment effect has been documented in now-famous experiments with mugs and chocolate of equivalent value: undergraduates doubled the value of the mug or chocolate they had after it was given to them (Kahneman et al. 1990).

In the same vein, behavioural economist Dan Ariely (2008) found that students at Duke University were willing to pay about $170 to buy basketball tickets on the black market but demanded $2,400 if the tickets were in their possession. In other words, the mere fact of possession added $2,230 to the value ascribed to the ticket. The endowment effect can also be used to explain why willingness-to-accept surveys generally produce higher values than willingness-to-pay surveys for things as diverse as postal service, trees and goose hunting permits (Kahneman et al. 1990). Clearly, the endowment effect and the consequent difference between willingness-to-accept and willingness-to-pay prices defy the law of one price assumed in standard economics. It also raises the question of how policymakers should assess costs and benefits.

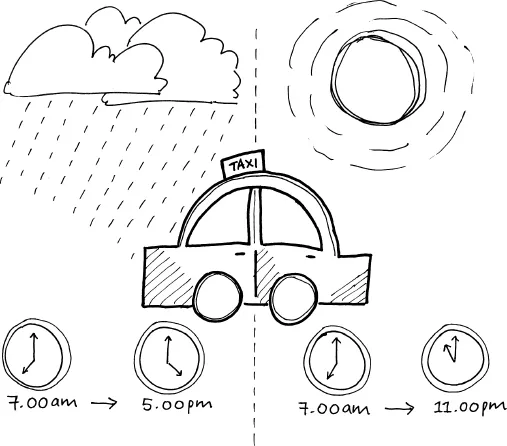

Yet another twist to standard cost-benefit analysis is the idea of mental accounting, which can be understood as a heuristic people use to simplify complicated and uncertain decisions. The theory is that we assign our expenditures to specific categories or mental accounts, such as housing, food, leisure and so on, and we balance costs and benefits on an account basis, rather than an overall basis (Thaler 1999). Mental accounting and loss aversion together can result in sub-optimal decisions, as illustrated by a study of New York taxi drivers. New York taxi drivers pay a fixed rental fee for their taxis and keep all the money they earn from driving passengers. They can decide how long they want to drive each day. A study by Colin Camerer and his collaborators found that taxi drivers had an idea of how much they needed to earn per day and would work until they reached that point — meaning that they stopped early on good days, e.g. rainy days or when a convention was in town, and they stopped later on bad days, whereas the optimal strategy would be to work more on good days and cut their losses on bad days (Camerer et al. 1997).

Economists have also explored other bounds in “the inner environment of the mind”, as Simon puts it (since the bounds in the external environment were well known to economists), apart from bounds on rational thought and their implications for economic theory. In their introduction to behavioural economics, Thaler and Mullainathan identified two other bounds on rational action of particular interest to economists: bounded self-control and bounded selfishness (Mullainathan and Thaler 2000).

One manifestation of bounded self-control could be status quo bias or the tendency to stick with the current situation, either out of fear of the devil you don't know (arguably a manifestation of loss aversion) or, less charitably, laziness and procrastination. Another example of bounded self-control can be found in the area of savings. The life-cycle hypothesis suggests that we should smoothen income and consumption over our life-cycle — if we expect to earn most of our income when we are young, we should save more now, in anticipation of our old age. In practice, our consumption tracks income more closely than predicted by the life-cycle hypothesis (Mullainathan and Thaler 2000). One reason could be because of hyperbolic discount rates, leading us to heavily discount (or put a lot less value on) future utility more than a rational being would (Thaler and Shefrin 1981). Another could simply be a lack of self-control, or the gap between how much we think we should save and how much we do save. Imperfect self-control, and the knowledge of that imperfection, could explain the popularity of save-as-you-earn programmes despite their low interest returns. These programmes allow participants to make binding commitments to save a particular percentage of their pay every month, in effect imposing external constraints on their present selves for the sake of their future selves.

In an example of how policies can be designed to take advantage of insights from behavioural economics, Thaler teamed up with economist Shlomo Benartzi on the design of the Save More Tomorrow scheme. The problem they sought to address was the low take-up of corporate savings plans, even though many companies offered their employees incentives to participate in these plans. To counter hyperbolic discounting and loss aversion, the Save More Tomorrow scheme allowed p...