Introduction to the Theory of the Early Universe

Hot Big Bang Theory

- 488 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Introduction to the Theory of the Early Universe

Hot Big Bang Theory

About this book

This book is written from the viewpoint of a deep connection between cosmology and particle physics. It presents the results and ideas on both the homogeneous and isotropic Universe at the hot stage of its evolution and in later stages. The main chapters describe in a systematic and pedagogical way established facts and concepts on the early and the present Universe. The comprehensive treatment, hence, serves as a modern introduction to this rapidly developing field of science. To help in reading the chapters without having to constantly consult other texts, essential materials from General Relativity and the theory of elementary particles are collected in the appendices. Various hypotheses dealing with unsolved problems of cosmology, and often alternative to each other, are discussed at a more advanced level. These concern dark matter, dark energy, matter-antimatter asymmetry, etc.

This book is accompanied by another book by the same authors, Introduction to the Theory of the Early Universe: Cosmological Perturbations and Inflationary Theory and is available as a set.

Sample Chapter(s)

Chapter 1: Cosmology: A Preview (1,644 KB)

Chapter 11: Generation of Baryon Asymmetry (701 KB)

Contents:

- Cosmology: A Preview

- Homogeneous Isotropic Universe

- Dynamics of Cosmological Expansion

- ΛCDM: Cosmological Model with Dark Matter and Dark Energy

- Thermodynamics in Expanding Universe

- Recombination

- Relic Neutrinos

- Big Bang Nucleosynthesis

- Dark Matter

- Phase Transitions in the Early Universe

- Generation of Baryon Asymmetry

- Topological Defects and Solitons in the Universe

- Color Pages

Readership: Cosmologists, advanced undergraduate and graduate students.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Cosmology: A Preview

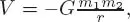

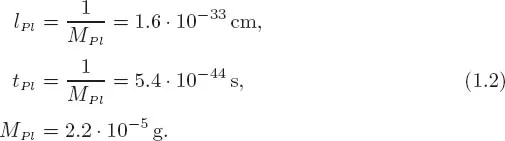

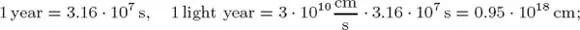

1.1 Units

Energy | 1 GeV = 1.6 · 10−3 erg |

Mass | 1 GeV = 1.8 · 10−24 g |

Temperature | 1 GeV = 1.2 · 1013 K |

Length | 1 GeV−1 = 2.0 · 10−14 cm |

Time | 1 GeV−1 = 6.6 · 10−25 s |

Particle number density | 1 GeV3 = 1.3 · 1041 cm−3 |

Energy density | 1 GeV4 = 2.1 · 1038 erg · cm−3 |

Mass density | 1 GeV4 = 2.3 · 1017 g · cm−3 |

Energy | 1 erg = 6.2 · 102 GeV |

Mass | 1g = 5.6 · 1023 GeV |

Temperature | 1 K = 8.6 · 10−14 GeV |

Length | 1 cm = 5.1 · 1013 GeV−1 |

Time | 1 s = 1.5 · 1024 GeV−1 |

Particle number density | 1 cm−3 = 7.7 · 10−42 GeV3 |

Energy density | 1 erg · cm−3 = 4.8 · 10−39 GeV4 |

Mass density | 1 g · cm−3 = 4.3 · 10−18 GeV4 |

1.2 The Universe Today

1.2.1 Homogeneity and isotropy

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Cosmology: A Preview

- 2. Homogeneous Isotropic Universe

- 3. Dynamics of Cosmological Expansion

- 4. ΛCDM: Cosmological Model with Dark Matter and Dark Energy

- 5. Thermodynamics in Expanding Universe

- 6. Recombination

- 7. Relic Neutrinos

- 8. Big Bang Nucleosynthesis

- 9. Dark Matter

- 10. Phase Transitions in the Early Universe

- 11. Generation of Baryon Asymmetry

- 12. Topological Defects and Solitons in the Universe

- 13. Color Pages

- Appendix A Elements of General Relativity

- Appendix B Standard Model of Particle Physics

- Appendix C Neutrino Oscillations

- Appendix D Quantum Field Theory at Finite Temperature

- Books and Reviews

- Bibliography

- Index