![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1. Towards Conscious Robots

Why is it so hard to make computers to understand anything and why is it equally hard to design sentient robots with the ability to behave sensibly in everyday situations and environments? The traditional approach of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has not been able to solve these problems. The modest computing power of the early computers in the fifties was seen as the main limiting factor for Artificial Intelligence, but today, when hundreds of gigabytes of memory can be packed into miniscule microchips, this excuse is no longer valid.

Machines still do not understand anything, because they do not operate with meanings. Understanding everyday meanings calls for embodiment. The machine must be able to interact with its environment and learn how things are. We humans do this effortlessly, we see and understand our environment directly and can readily interact with it according to the varying requirements of each moment. We can do this, because we are conscious. Our existing robots cannot do this.

Traditional Artificial Intelligence has not been able to create conscious robots (except in science fiction movies) and it is very likely that it never will (for the reasons explained later on in this book), therefore novel approaches must be found. We know, how conscious subjects behave and we could make machines imitate conscious behavior using the traditional AI methods. However, the mere imitation of conscious behavior is not enough, imitation has its limits and may fail any moment. The only universal solution would be the creation of truly conscious machines, if we only knew what it takes to be conscious.

The philosophy of mind has tried to solve the mystery of consciousness, but with limited success. Contradicting opinions among philosophers abound, as was demonstrated by Aaron Sloman’s target paper [Sloman 2010] and the responses to it in the International Journal of Machine Consciousness Vol. 2, No 1.

Psychology has not done much better. Neurosciences may be able to associate some neural activities with conscious states, but how these neural activities could give rise to the experience of being conscious has remained unexplained.

Could engineering do better? Engineers are familiar with complex systems. They know, how components can be combined into systems that execute complicated functions. The creation of a cognitive machine should thus be just another engineering project; feasible and executable as soon as the desired functions are defined. These definitions could be delivered by cognitive sciences. No doubt, machines that behave as if they were more or less conscious can be eventually created. But, were these machines really conscious? Would they have the experience of being conscious? If not, then no real consciousness has been created and the machines would only be mere replicas of the original thing, looking real, but not delivering the bullet.

The bullet must be delivered and conscious robots must be aware of their own thoughts and their own existence and know what they are doing. Unfortunately, there has been no engineering definition for the experience of being conscious. Philosophers have been pondering this question for couple of thousand years and have come to the conclusion that the phenomenon of consciousness seems to involve a problem that is hard or even impossible to solve in terms of physical sciences. This issue is known as the mind-body problem. The mind involves the experience of being conscious; how could this be explained with the application of the laws of physics? The natural laws of physics are able to explain the workings of energy and matter, electromagnetic fields, atoms and electrons and eventually the whole universe, for that matter. Yet the natural laws of physics have not been able to explain consciousness. Therefore, is consciousness something beyond energy and matter?

The central hypothesis beyond this book proposes that consciousness is neither energy nor matter and therefore it cannot be explained by the physical laws about energy and matter. However, consciousness is achievable by the application of energy and matter, because we already have an example of this kind of a conscious system; the human mind. Thus, the experience of being conscious seems to be a property of certain kinds of perceptual systems. Therefore, the explanation for consciousness would be found at the system level and the creation of robots with conscious minds should be possible. However, before the construction of conscious machines the real problem of consciousness must be identified, isolated and analyzed.

1.2. The Structure of This Book

This book begins with the review of the fundamental philosophical issues of consciousness. This treatment leads to the identification of the one and only real problem of consciousness. It is shown that this problem is related to perception and qualia, which are then discussed in detail. The existence of amodal qualia is proposed based on the known concept of amodal features and it is proposed that amodal qualia can give some insights into the phenomenal nature of qualia.

The relation of emotions and inner speech to consciousness is discussed next.

Can machines have qualia? It is argued that qualia are a mandatory prerequisite for human-like machine consciousness. Systems without qualia are not truly conscious. Next, some preconditions for machine qualia are proposed.

How do we know that a person or a machine is conscious? Some proposed tests exist and are presented and discussed here.

The identified preconditions for conscious cognition lead to the requirement of a perceptive system that combines sub-symbolic and symbolic information processing. Associative information processing with associative neural networks and distributed signal representations is introduced as a method for sub-symbolic processing that inherently facilitates the natural transition from sub-symbolic to symbolic processing.

Conscious robot cognition calls for information integration and sensorimotor integration and these lead to the requirement of an architecture, the assembly of cross-connected perception/response and motor modules. The Haikonen Cognitive Architecture (HCA) is presented as an example of a system that would satisfy the identified requirements.

Modern brain imaging technology seems to allow at least limited mind reading. It is proposed that the HCA might be used to augment mind reading technology. One already implemented example is cited.

Many cognitive architectures have been proposed lately and the comparison of their different approaches with the HCA would be interesting and in this way the approach of this book could be put in a wider perspective. However, a complete comparison is not feasible here, therefore a smaller review is attempted and the compared cognitive architectures are the Baars Global Workspace architecture and the Shanahan Architecture, as these are well-known and share many representative features with several other architectures.

Finally, as an example of a practical implementation of the Haikonen Cognitive Architecture, the author’s experimental cognitive robot XCR-1 is presented.

At the end of each chapter, where feasible, a chapter summary is provided for easy assimilation of the text. The concluding chapter of this book summarises the explanation of consciousness, as proposed by the author. This summary should be useful and should reveal the main points quickly.

![]()

Chapter 2

The Problem of Consciousness

2.1. Mind and Consciousness

What is conscious mind? This question has been studied by philosophers since old ages and no clear and definite answers have been found. The popular answer is of course that mind is what we have inside our head; our observations, thoughts, imaginations, reasoning, will, emotions and the unconscious processes that may lie behind these. Our mind is what makes us a person. The strange thing about the mind is that it is aware of itself; it is conscious.

It is useful to note that “mind” is an invented collective concept which encompasses many aspects of cognition and as such does not necessarily refer to any real single entity or substance, which may not really exist. However, in the following the word “mind” is used in the popular sense; mind is the system of perceptions, thoughts, feelings and memories, etc. with the sense of self.

There is concrete proof that the brain is the site of the mind. However, when we talk about mental processes, the processes of the mind in terms of cognitive psychology, we do not have to describe the actual neural workings of the brain (in fact, at the current state of the art, we are not even able to describe those in sufficient detail). Thus, the separation between the mind and the brain would seem be similar to the separation between computer software and hardware. However, the mind is not a computer program. It is not a string of executable commands that constitute an algorithm. It is not even an execution of any such program. Nevertheless, the apparent possibility to describe mental processes without resorting to the descriptions of neural processes would suggest that mental processes could be executed by different machineries, just like a computer program can be run in different hardware, be it based on relays, tubes, transistors or microcircuits. This leads to the founding hypothesis of machine consciousness; conscious agents do not have to be based on biology.

It is possible that we will properly understand mind only after the time when we will be able to create artificial minds that are comparable to their human counterpart. But, unfortunately, in order to be able to create artificial minds we would have to know what a mind is. This is a challenge to a design engineer, who is accustomed to design exotic gadgets as long as definite specifications are given. In this case the specifications may be fuzzy and incomplete and must be augmented during the course of construction.

Real minds are conscious, while computers are not, even though the supporting material machinery should not matter. Therefore, the mere reproduction of cognitive processes may not suffice for the production of conscious artificial minds. Thus, there would seem to be some additional factors that allow the apparently immaterial conscious mind to arise within the brain. These factors are related to the real problem of consciousness.

2.2. The Apparent Immateriality of the Mind

Is the mind some kind of immaterial process in the brain? When we work, we can see and feel our muscles working and eventually we get tired. There is no doubt that physical work is a material process. However, when we think and are aware of our environment, we do not see or feel any physical processes taking place. We are not aware of the neurons and synapses in the brain, nor the electrical pulses that they generate. We cannot perceive the material constitution and workings of the brain by our mental means. What we can perceive is the inner subjective experience in the forms of sensory percepts and our thoughts. These appear to be without any material basis; therefore the inner subjective experience would seem to be immaterial in that sense. Indeed, our thoughts and percepts about real external objects are a part of our mental content and as such are not real physical objects. There are no real people, cars and streets or any objects inside our heads, not even very, very small ones, no matter how vividly we imagine them; these are only ideas in our mind. Ideas are not the real material things that they represent, they are something else. Obviously there is a difference between the real physical world and the mind’s ideas of the same. The real physical world is a material one, but how about the world inside our head, our percepts, imaginations and feelings, the mental world? The philosophy of the mind has tried to solve this problem since old ages, but the proposed theories and explanations have led to further problems. These theories revolve around the basic problems, but they fail, because their angle of approach is not a correct one. In the following the problems of the old theories are highlighted and a new formulation of the problem of consciousness is outlined.

2.3. Cartesian Dualism

As an explanation to the problem of the conscious mind, The Greek philosopher Plato argued that two different worlds exist; the body is from the material world and the soul is from the world of ideas. Later on René Descartes suggested in his book The Discourse on the Method (1637) along the same lines that the body and the mind are of different substances. The body is a kind of a material machine that follows the laws of physics. The mind, on the other hand, is an immaterial entity that does not have to follow the laws of physics, but is nevertheless connected to the brain. According to Descartes, the immaterial mind and the material body interact; the immaterial mind controls the material body, but the body can also influence the mind. This view is known as Cartesian Dualism. Cartesian Dualism is also Substance Dualism as it maintains that two different substances, the material and the immaterial ones exist.

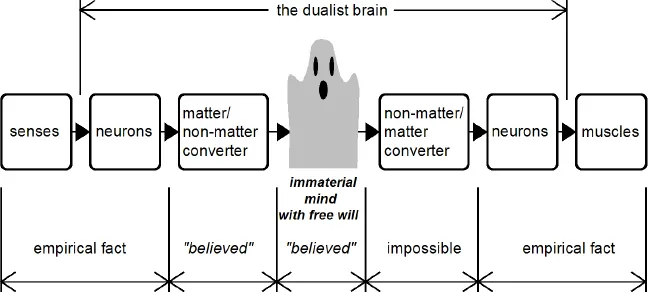

Is the dualist interpretation correct and do we really have an immaterial mind? This is a crucial issue for machine consciousness. Conscious machines should also have a mind with the presence of apparently immaterial subjective experience more or less similar to ours. The artificial mind should thus contain mental content, which would appear to the machine as immaterial, without the perception of any underlying material processes. Machines are material; therefore, if real minds were immaterial, then the creation of immaterial machine minds with the material means that are known to engineers today, would be impossible. The dualist view of mind is illustrated in Fig. 2.1.

Fig. 2.1. The dualist view of mind. Senses provide information about the material world in the form of material neural signals. These affect the immaterial mind, which, in turn controls the material neurons that operate the muscles. In this process a non-matter/matter converter is needed. This converter would violate physics as it would have to produce matter and/or energy out of nothing.

The dualistic approach may at first sight seem to succeed in explaining the subjective experience of the immaterial mind with the proposed existence of two different substances; the material substance of the physical world and the immaterial substance of the mind. Unfortunately, while doing so it leads to the mind-body interaction problem; how could an immaterial mind control a material body?

It is known that the brain receives information about the material world via sensors; eyes, ears, and other senses that are known to be material transducers. The information from these sensors is transmitted to the brain in the form of material neural signals. If the mind were immaterial, then the information carried by these neural signals would have to be transformed into the immaterial form of the mind. The immaterial mind would also have to be able to cause material consequences via muscles. It is known that the brain controls muscles via material neural signals; thus the command information created by the immaterial mind would have to be converted into these material signals. However, a converter that transforms immaterial information into material processes is impossible as energy and/or matter would have to be created from nothing.

Cartesian dualism has also another difficult problem that actually makes the whole idea unscientific. The assumed immaterial mind would power cognition and consciousness and would be the agent that does the thinking and wanting. But, how would it do it? Is there inside the brain some immaterial entity, a homunculus, that does the thinking and perceives what the senses provide to it? How would this entity do it? Immaterial entities are, by definition, beyond the inspection powers of material means, that is, the material instruments we have or might have in the future. Therefore we cannot get any objective information about the assumed immaterial workings of the mind; any information that we might believe to have via introspection would be as good as any imagination. (Psychology does not tell anything about the actual enabling mechanisms of the mind. In the same way, you will not learn anything about the innards of a computer by inspecting the outward appearance and behavior of the executed programs.) Thus, the nature of the immaterial mind would remain in the twilight zones of imagination and make-believe, outside the realm of sound empirically testable science. By resorting to the immaterial mind, Cartesian dualism has explained what is to be explained by unexplainable; this is not science, this is not sound reasoning, this is not reasoning at all.

The conclu...