![]()

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Why analyze costs? Cost is an integral part of planning and managing systems. Unlike other system properties, such as performance, functionality size, and environmental footprint, cost is always important, always must be understood, and never becomes dated in the eyes of management. As pressure increases to bring products to market faster and to lower overall costs, the earlier an organization can understand the cost of manufacturing and support, the better. All too often, managers lack critical cost information with which to make informed decisions about whether to proceed with a product, how to support a product, or even how much to charge for a product.

Cost can represent a “golden metric” or benchmark for analyzing and comparing products and systems. Cost, if computed comprehensively enough, can combine multiple manufacturability, quality, availability, and timing attributes together into a single measure that everyone comprehends.

1.1. Cost Modeling

Cost modeling is one of the most common business activities performed in an organization. But what is cost modeling, or maybe more importantly, what is it not? The goal of cost modeling is to enable the estimation of product or system life-cycle costs. Cost analyses generally take one of two forms:

• Ex post facto (after the event) — Cost is often computed after expenditures have been made. Accounting represents the use of cost as an objective measure for recording and assessing the financial performance of an organization and deals with what either has been done or what is currently being done within an organization, not what will be done in the future. The accountant's cost is a financial snapshot of the organization at one particular moment in time.

• A priori (prior to) — These cost estimations are made before manufacturing, operation and support activities take place.

Cost modeling is an a priori analysis. It is the imposition of structure, incorporation of knowledge, and inclusion of technology in order to map the description of a product (geometry, materials, design rules, and architecture), conditions for its manufacture (processes, resources, etc.), and conditions for its use (usage environment, lifetime expectation, training and support requirements) into a forecast of the required monetary expenditures. Note, this definition does not specify from whom the monetary resources will be required — that is, they may be required from the manufacturer, the customer, or a combination of both.

Engineering economics treats the analysis of the economic effects of engineering decisions and is often identified with capital allocation problems. Engineering economics provides a rigorous methodology for comparing investment or disinvestment alternatives that include the time value of money, equivalence, present and future value, rate of return, depreciation, break-even analysis, cash flow, inflation, taxes, and so forth. While it would be wrong to say that this book is not an engineering economics book (it is), its focus is on the detailed cost modeling necessary to support engineering economic analyses with the inputs required for making investment decisions. However, while traditional engineering economics is focused on the financial aspects of cost, cost modeling deals with modeling the processes and activities associated with the manufacturing and support of products and systems.

Unfortunately, it is news to many engineers that the cost of products is not simply the sum of the costs of the bill of materials. An undergraduate mechanical engineering student at the University of Maryland, in his final report from a design class, stated: “The sum total cost to produce each accessory is 0.34+0.29+0.56+0.65+0.10+0.17 = $2.11 [the bill of materials cost]. Since some estimations had to be made, $2.00 will arbitrarily be added to the cost of [the] product to help cover costs not accounted for. This number is arbitrary only in the sense that it was chosen at random.” Unfortunately, analyses like this are only too prevalent in the engineering community and traditional engineering economics texts don't necessarily provide the tools to remedy this problem.

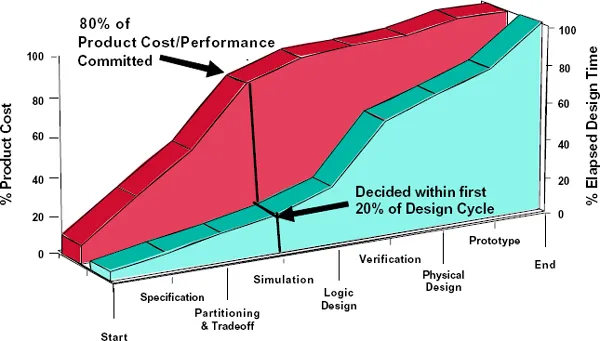

Fig. 1.1. 80% of the manufacturing cost and performance of a product is committed in the first 20% of the design cycle, [Ref. 1.1].

Cost modeling is needed because the decisions made early in the design process for a product or system often effectively commit a significant portion of the future cost of a product. Figure 1.1 shows a representation of the product manufacturing cost commitment associated with various product development processes. Even though it is not represented in Fig. 1.1, the majority of the product's life-cycle cost is also committed via decisions made early in the design process.

Cost modeling, like any other modeling activity, is fraught with weaknesses. A well-known quote from George Box, “Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful,” [Ref. 1.2] is appropriate for describing cost modeling. First, cost modeling is a “garbage in, garbage out” activity — if the input data is inaccurate, the values predicted by the model will be inaccurate. That said, cost modeling is generally combined with various uncertainty analysis techniques that allow inputs to be expressed as ranges and distributions rather than point values (see Chapter 9). Obtaining absolute accuracy from cost models depends on having some sort of real-world data to use for calibration. To this end, the essence of cost modeling is summed up by the following observation from Norm Augustine [Ref. 1.3]:

“Much cost estimation seems to use an approach descended from the technique widely used to weigh hogs in Texas. It is alleged that in this process, after catching the hog and tying it to one end of a teeter-totter arrangement, everyone searches for a stone which, when placed on the other end of the apparatus, exactly balances the weight of the hog. When such a stone is eventually found, everyone gathers around and tries to guess the weight of the stone. Such is the science of cost estimating.”

Nonetheless, when absolute accuracy is impossible, relatively accurate costs models can often be very useful.1

1.2. The Product Life Cycle

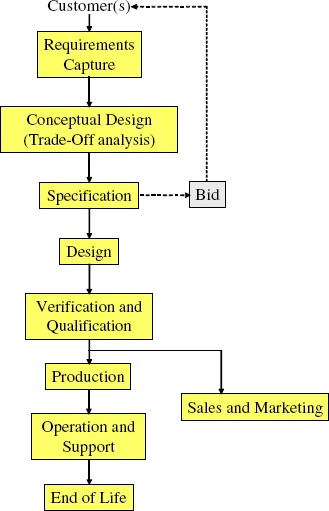

Figure 1.2 provides a high-level summary of a product's life cycle. Note that not all the steps that appear in Fig. 1.2 will be relevant for every type of electronic product and that more detail can certainly be added. Product life cycles for electronic systems vary widely and the treatment in this section is intended to be only an example.

In the process shown, a specific customer provides the requirements or a marketing organization determines the requirements through interactions in the marketplace with customers and competitors. Conceptual design encompasses selection of system architecture, possibly technologies, and potentially key parts.

Specifications are engineering's response to requirements and results in a bid that goes to the customer or to the marketing organization. The bid is a cost estimation against the specifications. Design represents all the activities necessary to perform the detailed design and prototyping of the product. Verification and qualification are activities to determine if the design fulfills the specifications and requirements. Qualification occurs at the functional and environmental (reliability) levels, and may also include certification activities that are necessary to sell or deliver the product to the customer. Production is the manufacturing process and includes sourcing the parts, assembly, and recurring functional testing. Operation and support (O&S) represents the use and sustainment of the product or system. O&S represents recurring use — for example, power, water, or fuel — as well as maintenance, servicing the warranty, training and support for users, and liability. Sales and marketing occur concurrent with production and operation and support. Finally, end of life represents activities needed to terminate the use of the product or system, including possible disassembly and/or disposal.

Fig. 1.2. Example product/system life cycle.

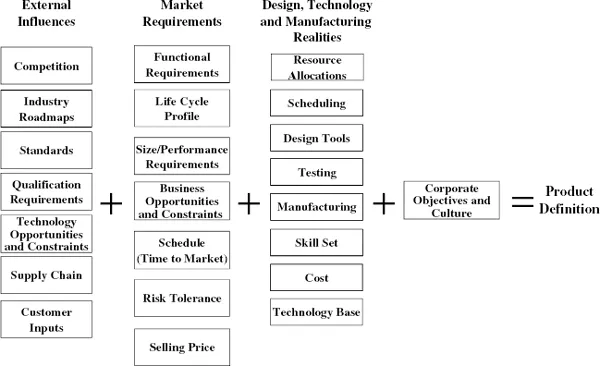

A common thread through the activities in the life cycle of a product or system is that they all cost money. The product requirements are of particular interest since they ultimately determine the majority of the cost of a product or system and also represent the primary and initial inputs for cost modeling. The requirements will, of course, be refined throughout the design process, but they are the inputs for the initial cost estimation. Figure 1.3 shows the elements that go into the product requirements.

Fig. 1.3. Product/system requirements, [Ref. 1.4].

1.3. Life-Cycle Cost Scope

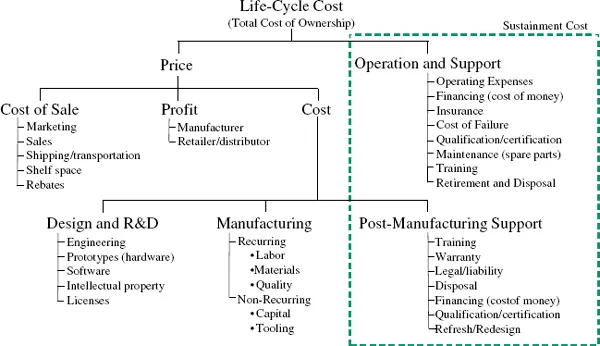

The factors that influence cost analysis are shown in Fig. 1.4. For low-cost, high-volume products, the manufacturer of the product seeks to maximize the profit by minimizing its cost. For a high-volume consumer electronics product (e.g., a cell phone), the cost may be dominated by the bill of materials cost. However, for some products, a more important customer requirement for the product may be minimizing the total cost of ownership of the product. The total cost of ownership includes not only the cost of purchasing the product, but the cost of maintaining and using it, which for some products can be significant. Consider an inkjet printer that sells for as little as $20. A replacement ink cartridge may cost $40 or more. Although the cost of the printer is a factor in deciding what printer to purchase, the cost and number of pages printed by each ink cartridge contributes much more to the total cost of ownership of the printer. For products such as aircraft, the operation and support costs can represent as much as 80% of the total cost of ownership.

Fig. 1.4. The scope of cost analysis (after [Ref. 1.5]).

Since manufacturing cost and the cost of ownership are both important, Part I of this book focuses on manufacturing cost modeling and Part II expands the treatment to include life-cycle costs and takes a broader view of the cost of ownership.

1.4. Cost Modeling Definitions

It is important to understand several basic cost modeling concepts to follow the technical development in this book. Many of these ideas will be expanded upon in the chapters that follow.

Price is the amount of money that a customer pays to purchase or procure a product or service.

Cost is the amount of money that the manufacturer/supporter of a product or system or the supplier of a service requires to produce and/or provide the product or service. Cost includes money, time and labor.

Profit is the difference between price and cost. Thus,

Technically, profit is the excess revenue beyond cost. Profit is an accounting approximation of the earnings of a company after taxes, cash, and expenses. Note that profit may be collected by different entities throughout the supply chain of the product or system.

Recurring costs, also referred to as “variable” cos...