![]()

Chapter 1

Modern ideas of

gravitation and

cosmology — a brief essay

At the beginning of the 20th century, only two physical fields were known, electromagnetic and gravitational. Einstein’s theory of special relativity (SR), created in 1902-1905, described quite well the mechanical and electromagnetic phenomena at velocities up to the velocity of light, which had been impossible in the framework of Galileo and Newton’s classical approach. However, Newton’s theory of gravity, which was almost a perfect basis for celestial mechanics and all terrestrial physics, was formulated using the old notions of absolute space and time and could not be reconciled with SR where space and time were unified in Minkowski’s four-dimensional geometry.

After the advent of SR there were numerous attempts to describe the gravitational field in Minkowski space in the hope to include rapidly moving gravitating objects into the theory. Newtonian gravity in such cases ought to be recovered in the limit of small velocities.

Henri Poincaré, great French mathematician who had actually “discovered” SR simultaneously with Einstein, was the first to try to extend it to gravity, assuming a finite propagation velocity of the gravitational field. The idea that gravity is transferred with the speed of light had been expressed before, but without SR there was no proper geometric language for such ideas to underlie a consistent theory. But the fate of special-relativistic theories of gravity was also not too happy. Despite being intrinsically free of contradiction, they still faced serious problems. One of them was their inability to explain the anomalous secular perihelion advance of planet Mercury’s orbit, about 43′′ per century, which could not be explained by Newton’s theory as well. This perihelion shift had been quite confidently measured in astronomical observations.

By the way, Mercury is the fastest planet of the Solar system, and it was natural to expect a manifestation of the new “gravity of high velocities” in the peculiarities of its motion.

By Kepler’s laws, which follow from Newton’s universal law of gravity, the planets of the Solar system move along closed elliptic orbits. This ideal picture is true if each planet interacted with the Sun only. In reality, the mutual influence of the planets upon each other slightly changes their orbits, so that their ellipses slowly rotate from one revolution to another, thus becoming unclosed spiral-like curves. These effects are calculated in Newtonian celestial mechanics with high accuracy. The anomalous perihelion shift is obtained by subtracting all “normal” shifts (explained in Newtonian physics by coordinate effects and gravitational perturbations due to other planets, whose sum amounts to about 5558 angular seconds per century) from the observed value of 5601″ per century (see, e.g., [417] for details).

One more circumstance of theoretical nature made any attempts to describe gravity in the framework of SR, so to say, less attractive. Since Galilean times it has been well known that, if one excludes air resistance, quite different bodies — a bit of fluff, a wooden bar, a brick, a lead ingot, a can of water etc. — fall to Earth with precisely the same acceleration. The universality of free-fall acceleration was confirmed with high accuracy (up to 10−9) in the Eötvös experiment with a torsion balance at the end of the 19th century: in fact, it established an equivalence between the Earth’s attraction force and the inertial centrifugal force due to the Earth’s diurnal rotation. In Newton’s equations it is expressed as an equality between the inertial and gravitational masses, the so-called equivalence principle (EP). Newton’s theory itself cannot explain this equality, as well as all its generalizations in the framework of SR.

The inertial mass that appears in the second law of Newtonian mechanics

(acceleration is equal to force divided by mass) and the gravitational mass that appears in the law of gravity are, in essence, quantities of absolutely different physical nature. It was clear to Einstein that an equality between them cannot be a mere coincidence and should have

deep reasons. The universality of the action of gravity on all bodies led him to the idea that became the basis of general relativity (GR): the gravitational field is a property of space itself, and this property should change from point to point since the gravitational field is, in general, inhomogeneous. Therefore, the Minkowski space, which is flat, homogeneous (the same at all its points) and isotropic (the same in all directions) is not suitable; gravity should warp and curve it. That is how emerges the idea of curvature of physical space-time. And since the gravitational field is created by heavy bodies, the same must be true for the curvature.

Certainly the main idea of GR, as any fundamental idea, had its forerunners and proclaimers. Even N.I. Lobachevsky, discoverer of non-Euclidean geometry, spoke in 1826 of a possible experimental determination of the world’s geometry. Riemann (1854) and Clifford (1876) assumed that the curvature of space must depend on the properties of matter that fill it, and Clifford even expressed the idea that curvature may propagate by waves. So the ideas as though wandered in air. But it was Einstein (in contact with Hilbert, Poincaré and other outstanding mathematicians and physicists of that time) who converted them into an elegant and logically consistent theory.

The fruit was ripe by 1915. GR became one more step aside from the simple and clear views of classical physics: the four-dimensional space-time (or simply space, as is often said for brevity) became curved. Riemannian geometry, the geometry of curved spaces, already invented by that time, became a mathematical tool and a language of the new physical theory.

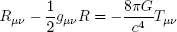

In Riemannian geometry, hence also in GR, the basic quantity used to describe the space-time is the symmetric metric tensor gµν(xα) (the metric), which depends on the four coordinates xµ and consequently changes from point to point. The metric carries information on intervals between close space-time points, or events, and in its terms one expresses the quantities that directly characterize the space-time curvature, the Riemann and Ricci tensors. It is the metric tensor components that are the unknowns in the dynamic equations of GR, the Einstein equations (or the Hilbert-Einstein equations, as they are sometimes called to emphasize Hilbert’s substantial contribution in GR’s creation):

(1.1)

In the general case, it is a set of ten nonlinear partial differential equations with respect to ten unknown functions of four space-time coordinates. Their basic sense is a direct relationship between the space-time curvature (the left-hand side of the equations, called the Einstein tensor) and the distribution and motion of matter (the right-hand side of the equations, called the stress-energy tensor). Thus “matter tells space how to curve”. Any solution to the Einstein equations describes some possible configuration of matter and the gravitational field.

Just as SR did not cancel Newton’s mechanics (quite suitable at small velocities), GR did not cancel SR, which is valid in any small region of a curved but smooth space-time. The smaller the size of such a region, the more precisely this region coincides with a certain region of the Minkowski flat tangent space, and with greater accuracy hold SR and its numerous consequences. The Newtonian theory of gravity also follows from GR under proper conditions: Newton’s equations are obtained from those of GR in the limit of small curvature (that is, in weak gravitational fields) and small relative velocities of the gravitating bodies. Most of the observable phenomena belong to this “weak regime”. But GR interprets the gravitational forces in quite a different manner: these are now not forces but certain geometric characteristics of the world lines along which the bodies move in four-dimensional space-time. From the viewpoint of GR, a body falling freely in a gravitational field moves without any external forces, and its world line is a geodesic, a direct analogue of a straight line in flat space.

A phenomenon of utmost importance, absent in Newton’s theory but predicted by GR, is the gravitational waves. Their existence directly follows from the wave nature of GR equations and is confirmed (though so far only theoretically) by their numerous wave solutions. There is also indirect experimental data confirming their existence based on an analysis of pulsar dynamics: a binary pulsar loses its energy just as predicted by the general-relativistic radiation formulas.

GR readily responded to the observational challenge and surprisingly precisely explained the above-mentioned anomaly in Mercury’s motion. Another classical effect of GR available to verification is the effect of gravity on light rays, leading to light bending in the field of a celestial body. By Einstein’s calculation, light passing near the Sun should be bent by an angle of 1,75″ . A similar effect is obtained in Newtonian theory if one represents light as a flow of particles flying, naturally, with the speed of light. But then the calculated bending will be half as much as in GR: approximately 0,87″ for a ray passing near the edge of the solar disk.

The total eclipse of the Sun on 29 May 1919 made it possible to measure this effect by comparing the photos of stars near the solar disk closed by the Moon with usual night photos of the same part of the sky. As was expected, for pictures taken during the eclipse, the stars turned out to be slightly shifted from the disk edge as compared to their night positions. The deflection angle varied in different observers’ data from 1,61″ to 1,98″ near the disk edge, gradually diminishing in the outward direction, at an error within 30″ . So the sky confirmed the rightness of Einstein’s prediction.

It was a true triumph: a theory created on the tip of a pen, swiftly won a place under the Sun. And what is even more amazing is that it generally preserves its leading position even now, withstanding the challenges of time and lots of experiments.

Einstein after Einstein

But let us not “run ahead of the engine” and return to the 20s and 30s of last century. It was the time of physics’ active penetration into the micro-world and formation of a language adequate to its properties — quantum mechanics, later quantum electrodynamics and, wider, quantum field theory. The quantum theory was first built in the framework of the old, Newtonian concepts of absolute time and absolute space (nonrelativistic quantum mechanics), and it required substantial effort to extend it to the world of large velocities and high energies and to formulate its content in Minkowski’s four-dimensional space-time.

The understanding of gravity as space-time curvature endowed GR with an exclusive character as compared to all the rest of physics, and this was in conflict with the feeling of unity of the material world, important for both philosophers and physicists. On the other hand, in GR itself there emerge quite a number of important problems, one of which is known as the problem of energy. The notions of energy and other conserved quantities play a very significant part in the structure of quantum theory. In flat space, one easily formulates the energy, momentum and angular moment conservation laws due to the symmetry of Minkowski space with respect to temporal and spatial translations and rotations, forming the 10-parameter Poincaré group. In curved space-time there are no such symmetries at all, and it is therefore quite difficult to define the energy and momentum of the gravitational field in GR in a consistent way.

For this and some other reasons, not all physicists have agreed with GR, and even now there are repeated attempts to build a theory of gravity in Minkowski space. Unlike the first attempts of this kind, the new authors have learned to explain the classical observed effects of GR, and gravitation in such theories is represented by a field with normal conservation laws and hopes to be quantized on equal grounds with other physical fields. According to Will’s book [425], as early as in 1960 the number of such theories exceeded 25. But neither then nor afterwards did such theories give rise to really substantial interest (though certainly their followers would not agree with such a conclusion).

Going the other way, the contrary trend “to reduce all physics to geometry” created a number of new ideas which even now remain topical in theoretical physics. In this connection, GR was considered (and is now considered) as a basis for extension which can be achieved by introducing more complicated geometries than the Riemannian one (Weyl, Eddington, Cartan), space-time dimension larger than four with additional invisible coordinates (Kaluza, Klein), and new requirements to the symmetry of the initial formulation of the theory (Weyl’s gauge symmetry principle). An ambitious task was then formulated, going far beyond a simple unification of the gravitational and electromagnetic fields: to obtain, from a unified field, all characteristics of the small number of elementary particles known at that time. And Einstein was not aside from all this effort, he was a leader of the program aimed at building a unified field theory on the basis of GR, and he remained that leader to the end of his life.

A description of these attempts would lead us too much away from our main subject, gravitation. Therefore we would like only refer to Heisenberg’s words said in the early 60s: “It has been in essence a splendid attempt But at the time when Einstein developed his unified field theory, more and more new elementary particles were discovered, with their corresponding new fields. So there did not exist a steady empirical basis for carrying out Einstein’s program, and his attempt did not lead to any convincing results.” [Back translation from Russian.]

Even today the problem of creating a “theory of everything” remains a central problem of theoretical physics.

The technological breakthrough

By the end of the 1950s, physics already knew four rather than two basic interactions: the gravitational, electromagnetic, strong nuclear (due to which protons and neutrons join to form atomic nuclei) and weak nuclear (which is responsible for many particle transmutations and nuclear reactions of which the most well-known is beta decay). Among them, the gravitational interaction appeared to be something of minor importance: for particles, being much weaker than even the weak interaction, it seemed absolutely insignificant in micro-world physics. The accelerators supplied more and more new experimental data about the other three interactions, and quantum field theory in flat Minkowski space experienced rapid progress, formulating and solving various problems of particle physics. Against such a background, gravitational studies seemed to be something of extravagance. Yes, GR was recognized as a fundamental, almost philosophical theory, important for the world outlook, but its experimental basis was too poor: one effect, Mercury’s perihelion advance, was checked up to 1%, and another, light bending near the Sun, up to roughly 30%. The cosmological observations could only testify to a nontrivial geometry of the Universe but could tell nothing about the validity of particular gravitational equations... Kip Thorne, at that time a student and now one of the most famous gravitational physicists, was advised by his professors not to deal with GR, which, in their opinion, was a theory very weakly connected with the rest of physics and astronomy. He did not obey such an advice and, as far as we can guess, hardly regrets now.

The situation began to change only in the late 50s and early 60s. The development of experimental technology made it possible to plan and carry out a number of new tests of gravity while astronomical observations gave more and more evidence of the existence of real sources of strong gravitational fields in space. As the number of alternative theories of gravity grew, tens of new effects were predicted along with suggestions to test them.

Amazingly it is GR that is being confirmed now with greater and greater accuracy. Very briefly, that is how the present experimental status of GR looks.

One of the fundamentals of GR, the equivalence principle, has been confirmed, using torsion balances and various test bodies, to an impressing accuracy of 10−12 by now [46]. It seems that the limit of experiments on Earth’s surface has been reached by this result, due to inevitable atmospheric, seismic, and technological noise. The planned satellite experiment STEP (Satellite Test of the Equivalence Principle) [430] will raise the accuracy to 10−17 − 10−18 . The equivalence principle is predicted by all metric theories of gravity, including GR and its numerous extensions where gravity is identified with space-time curvature.

Another effect, which is also universal and common to a large class of theories is the so-called gravitational redshift. Its essence is quite simple: a photon, moving away from a gravitating centre, loses energy, hence its wavelength grows (the photon “reddens”), while if it approaches the centre, it gains energy and becomes “more blue”. In the same way a stone thrown up loses its speed but gains it while falling down. In GR this effect is also related to the clock slowing-down: the more we approach a source of gravity, the slower are clocks of the same physical nature. This effect has been checked both for photons (the experiments of Pound, Rebka and Snider with resonance photon absorption by atomic nuclei) [330, 331], and directly for clocks (deflections in precision atomic clock readings in air travels around the world) [193].

By the way it is this ef...