![]()

1

DIAGNOSIS AND CLASSIFICATION OF SEIZURES AND EPILEPSY SYNDROMES

Jorge Vidaurre and Anup Patel

Introduction

An epileptic seizure is the clinical manifestation (symptoms and signs) of excessive and hypersynchronous, usually self-limited, activity of neurons in the cerebral cortex. The term seizure does not imply a specific diagnosis. Instead, it defines a clinical event. Epilepsy, on the other hand, is defined as a chronic disorder characterized by recurrent (more than two) unprovoked seizures. Epilepsy is a diagnosis. Furthermore, when associated with specific EEG abnormalities and patient characteristics, epilepsy can be considered a syndrome.

The first step in the evaluation of a patient with a possible seizure is to confirm the event was indeed an epileptic seizure, as multiple disorders may manifest through events that mimic a seizure (Table 1). The clinical history remains the cornerstone of the diagnostic work-up. It is important to gather information about the events that occurred before, during, and after the episode. The neurological examination may be normal, but focal abnormalities suggest a structural brain lesion as the etiology of the seizures. According to the practice guidelines set forth by the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society, laboratory tests have limited usefulness in the evaluation of a patient who had a first seizure. A lumbar puncture is reserved for cases where a central nervous system infection is suspected.

Division of Child Neurology, Nationwide Children’s Hospital and The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

Table 1. Non-epileptic paroxysmal events in children.

Sandifer syndrome or gastroesophageal reflux disease Benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood Tics, stereotypies, and movement disorder Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures |

The electroencephalogram (EEG) is an important component of the diagnostic work-up, especially for patients who had an unprovoked event or for those in whom the event was of focal origin. As indicated above, interpretation of the EEG may help in the classification of an epilepsy syndrome. The EEG should, ideally, be recorded following a night of sleep deprivation. Such a measure increases the likelihood of recording EEG activity during drowsiness and sleep, which can increase the possibility of detecting abnormal discharges. An EEG where brain activity during these two states is not recorded would be considered to be an incomplete study.

Radiological studies, either a CT of the head or an MRI of the brain are indicated in most patients who present with partial seizures or if suspicion of a focal lesions exists. If available, a brain MRI is preferred as the resolution of the images is far superior to that which can be obtained through a CT scan of the head. If the event was preceded by head trauma, a head CT is the test of choice as it can be obtained expeditiously.

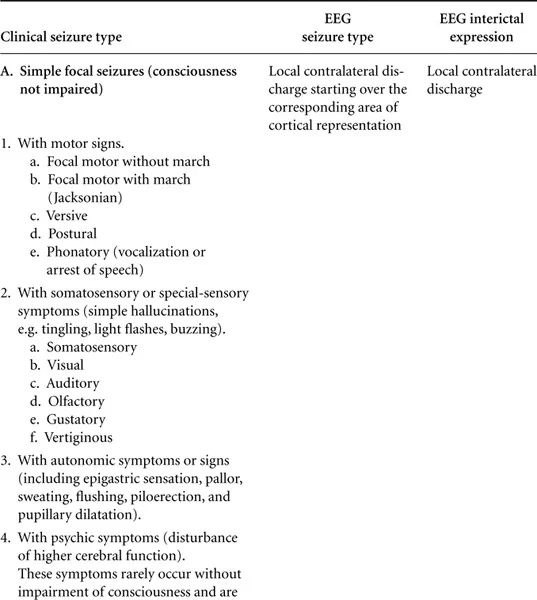

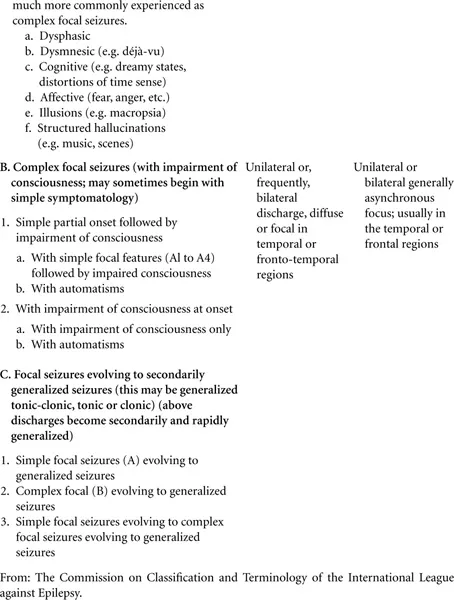

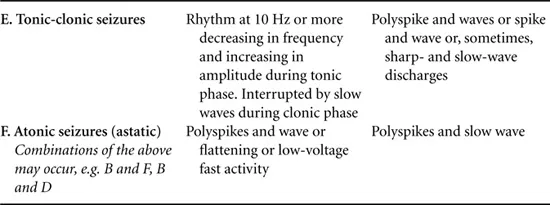

As indicated above, epilepsy is defined as two or more unprovoked seizures. After making the diagnosis of epilepsy, classifying the seizure and thus a specific epilepsy syndrome helps guide the treatment plan. In this chapter, the classification published by the Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) 1981 and 1989 was used. This classification is under current review, so it is our intention not to focus on the classification but on specific clinical and EEG characteristics of well-defined epilepsy syndromes (electroclinical syndromes by the new proposed terminology, see Table 4). The first step in seizure classification is to differentiate between generalized and partial (focal) seizures. Generalized seizures involve simultaneous activation of bi-hemispheric cortical regions, and are almost always accompanied by impairment of consciousness. When motor manifestations are present, they are usually symmetric and affect both sides of the body (Table 2). A generalized epilepsy syndrome may have different types of generalized seizures (Table 3).

Table 2. International league against epilepsy (ILAE) classification of seizures. ILAE classification of focal (partial, local) seizures

From: The Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League against Epilepsy.

Table 3. Epilepsy classification table. The International League against Epilepsy classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes.

I. Localization-related (focal, local, partial) epilepsies and syndromes

A. Idiopathic (with age-related onset). At present, two syndromes are established:

1. Benign childhood epilepsy with centro temporal spikes

2. Childhood epilepsy with occipital paroxysms

B. Symptomatic. This category comprises syndromes of great individual variability.

II. Generalized epilepsies and syndromes

A. Idiopathic (with age-related onset, in order of age appearance)

1. Benign neonatal familial convulsions

2. Benign neonatal convulsions

3. Benign myoclonic epilepsy in infancy

4. Childhood absence epilepsy (pyknolepsy, petit mal)

5. Juvenile absence epilepsy

6. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

7. Epilepsy with grand mal seizures on awakening

B. Idiopathic, symptomatic, or both (in order of age of appearance)

1. Infantile Spasms

2. Lennox Gastaux

3. Epilepsy with myoclonic-astatic seizures

4. Epilepsy with myoclonic absences

C. Symptomatic

1. Nonspecific cause, early myoclonic encephalopathy

2. Specific syndromes. Epileptic seizures may complicate many disease states. Under this heading are included those diseases in which seizures are a presenting or predominant feature.

III. Epilepsies and syndromes undetermined as to whether they are focal or generalized

A. With both generalized and focal seizures

1. Neonatal seizures

2. Severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy

3. Epilepsy with continuous spikes and waves during slow-wave sleep

4. Acquired epileptic aphasia (Landau-Kleffner syndrome)

B. Without unequivocal generalized or focal features

IV. Special syndromes

A. Situation-related seizures

1. Febrile convulsions

2. Seizures related to other identifiable situations, such as stress, hormones, drugs, alcohol, or sleep deprivation

B. Isolated, apparently unprovoked epileptic events

C. Epilepsies characterized by the specific modes of seizures precipitated

D. Chronic progressive epilepsia partialis continua of childhood

From: The Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy.

Partial seizures affect only one portion of the brain. Hence, they usually have manifestations that involve only one body segment, and are not always associated with loss of consciousness. There are three subtypes of partial seizures: simple partial, complex partial and partial seizures with secondary generalization (Table 2). Simple partial seizures affect one portion of the brain, and consciousness is not affected. In contrast, complex partial seizures are associated with alteration of consciousness. Finally, partial seizures can become generalized. In such instances, the seizure focus is found in one brain hemisphere and then spreads to involve both hemispheres.

Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsy

A 15-year-old boy is evaluated in the emergency department for the chief complaint of a possible seizure. The event reportedly occurred at 9:00 a.m., immediately after the patient woke up from sleep. The episode is described as sudden onset of body stiffening followed by generalized tonic-clonic movements of the body and upward eye deviation. The event lasted 2 minutes. Subsequently, the youngster remained drowsy for a few hours; he has no recollection of the event. On further questioning, the patient indicates having experienced bilateral arm jerks usually early in the morning. On a few instances, also in the morning, he would drop objects held in his hands. Finally, the boy’s classmates have reported to the teachers that occasionally, the boy appeared confused and unresponsive during the school day. The boy denies using substances of abuse or having experienced head trauma. There is no history of developmental delay or academic difficulties. The family medical history is remarkable for seizures in a maternal cousin whose events became evident at the age of 13 years. The general neurological examination, complete blood count, and complete metabolic panel are within normal limits. The young man’s EEG has evidence of 4–6-Hz generalized spike – and polyspike-wave discharges activated by photic stimulation. Based on the clinical history and EEG abnormalities, it is determined that the boy has three seizure types: generalized tonic-clonic seizures, myoclonic seizures, and absence seizures. He is diagnosed with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME).

Discussion

In the abovementioned case, the patient was diagnosed with JME. JME is an epilepsy syndrome that becomes evident during puberty. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy accounts for 5–10% of all epilepsy cases. Three seizures types can be associated with this syndrome: myoclonic jerks, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and absence seizures. Myoclonic jerks usually affect the upper extremities, are not associated with alteration in consciousness, and mostly occur soon after waking up from sleep. The patient may drop objects they hold in their hands, which may make some confuse the jerks...