![]()

1

Molecular Structure and

Chemistry of Diamondoids

1.1. Introduction

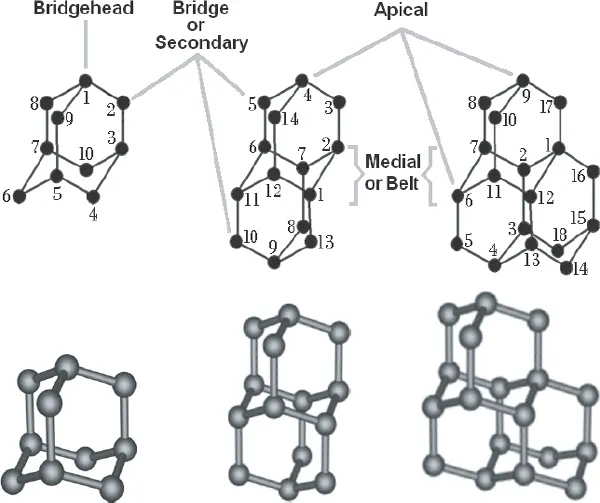

Diamondoid molecules are cage-like, ultra stable and saturated hydrocarbons. The basic repetitive unit of the diamondoids is a ten-carbon tetracyclic cage system called “adamantane” (Fig. 1.1). They are called “diamondoid” because they have at least one adamantane unit and their carbon-carbon framework is completely or largely superimposable on the diamond lattice (Balaban and Schleyer, 1978; Mansoori, 2007). The diamond lattices structure was first determined in 1913 by Bragg and Bragg using X-ray diffraction analysis (Bragg and Brag, 1913).

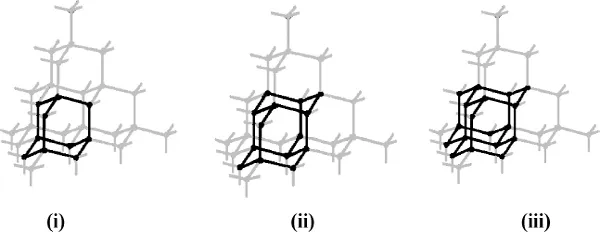

Diamondoids show unique properties due to their exceptional atomic arrangements. Adamantane consists of cyclohexane rings in “chair” conformation. The name adamantane is derived from the Greek language word for diamond since its chemical structure is like the three-dimensional diamond subunit as it is shown in Fig. 1.2.

1.2. Classification and Crystalline Structure of Diamondoids

The first and simplest member of the diamondoids group, adamantane, is a tricyclic saturated hydrocarbon (tricyclo[3.3.1.1(3.7)]decane, according to the von Bayer systematic nomenclature). Adamantane is followed by its polymantane homologs (adamantologs): diamantane, tria-, tetra-, penta-, and hexamantane. These molecules are particularly denominated polymantanes because they are completely superimposable on the diamond lattice (see Fig. 1.2) and all carbon atoms belong in a whole adamantane unit, in addition, each pair of units is face-fused (Balaban and Schleyer, 1978). In other words, each adamantane shares six carbon atoms with an adjacent unit. Figure 1.1 illustrates the smaller diamondoid molecules, with the general chemical formula C4n+6H4n+12: adamantane (C10H16), diamantane (C14H20), and triamantane (C18H24). Each of these three lower adamantologs has only one isomer.

Fig. 1.1. Three-dimensional molecular structures of (from left to right) adamantane, diamantane and triamantane, the smallest diamondoids, with chemical formulas C10H16, C14H20, and C18H24, respectively. Note that the bridgehead position 1 in adamantane is equivalent to positions 3, 5, and 7, while all four secondary or bridge positions are equivalent to each other. Note that diamantane and triamantane have two types of bridgehead carbons: atoms at positions 4 and 9 of diamantane and 9 and 15 in triamantane are in equivalent apical positions. Carbon atoms 1, 2, 6, 7, 11, and 12 in diamantane are medial or belt; as are atoms 2 (equivalent to 12), 6 (equivalent to 4), 7 (equivalent to 11), 3 (equivalent to 13) in triamantane (Fort, 1976; Olah, 1990a; Ramezani et al., 2007).

Fig. 1.2. The relation between lattice diamond structure and (i) adamantane, (ii) diamantane, and (iii) triamantane structures (Mansoori, 2007).

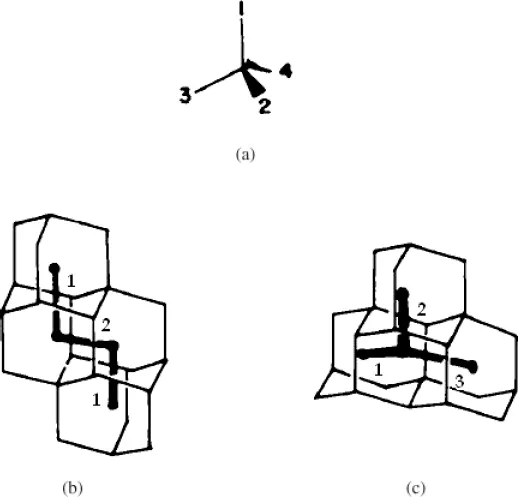

In 1978, Balaban and Schleyer created a systematic enumeration of polymantanes (Balaban and Schleyer, 1978). At that time, the larger known adamantolog was tetramantane, nevertheless the authors proposed a new code, based on graph-theory approach using dual-graphs. This was in anticipation of eventual preparation of higher diamondoids and to avoid use of trivial names which would probably be invented to distinguish isomeric polymantanes. Dual-graphs or dualist graphs of polymantanes are built by joining the centers of fused adamantane units. These graphs are coded using digits 1-4 as symbols of the four possible orientations in space of adamantane units in a polymantane structure (Fig. 1.3a).

Using these concepts, one could represent adamantane as a point and diamantane as an edge. Figure 1.3b shows a representation of the dualist graph for one of the isomers of tetramantane called anti-tetramantane (the same as [121]tetramantanes shown on Fig. 1.4). Note that this graph is acyclic linear, while Fig. 1.3c exhibits an acyclic branched graph for iso-tetramantane (the same as [1(2)3]tetramantane shown on Fig. 1.4).

Both isomers are classified as cata-condensed isomers or catamantanes as their dual graphs are open. Molecules like [12312]hexamantane (Fig. 1.4), in their turn, are peri-condensed polymantanes or perimantanes, as their dual-graphs are cyclic. To code polymantanes according to Balaban and Schleyer, it is necessary to number each different direction taken by the dual graph, starting from one endpoint of the longest chain. The final set of digits has to form the smallest number possible. For example, diamantane has code 1, because its dual graph is a straight line (one possible direction, smallest possible number), and triamantane has code 12 (two lines forming a 109°28' angle, first direction is 1, second is 2). Anti-tetramantane is [121]tetramantane, and iso-tetramantane, with its tree-like dualist graph, is coded [1(2)3] (parentheses indicate a branch). Balaban and Schleyer nomenclature is widely used for diamondoids and will be preferably used in this book.

Fig. 1.3. Dualist graphs of polymantanes. (a) Four possible relative directions for face-fused adamantane units, (b) Anti-tetramantane and (c) Iso-tetramantane with their dual-graph showing the numbering of each direction (Balaban and Schleyer, 1978).

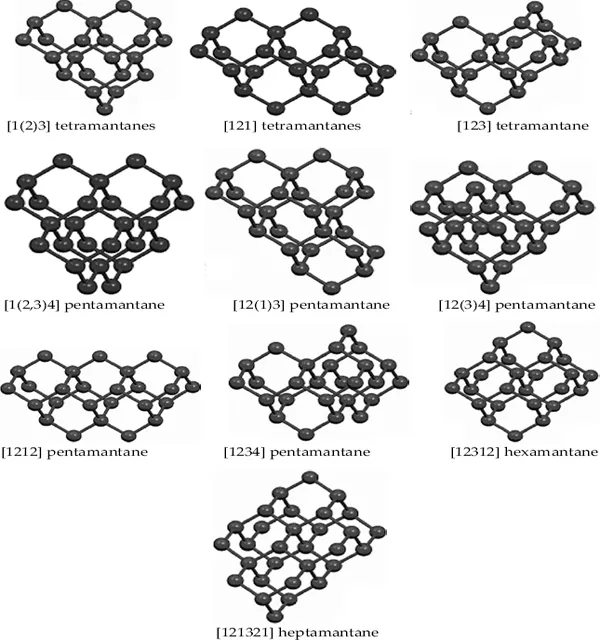

Depending on the spatial arrangement of the adamantane units, higher polymantanes (n > 4) can have several isomers and nonisomeric equivalents. There are three possible tetramantanes, all of which are isomeric. They are depicted in Fig. 1.4 as [1(2)3] (or iso-), [121] (or anti-), and [123] (or skew) tetramantane (only one enantiomer is shown). [121] and [123]tetramantanes each possess two quaternary carbon atoms, whereas [1(2)3]tetramantane has three. The number of diamondoid isomers increases appreciably after tetramantane.

With regard to the remaining members of the diamondoid group, there are ten possible pentamantanes, nine of which are isomeric (C26H32) and follow the molecular formula (C4n+6H4n+12) of the homologous series and one is nonisomeric (C25H30). For hexamantane, there are 39 possible structures: 28 are regular cata-condensed isomers with the chemical formula C30H36, 10 are irregular cata-condensed isomers with the chemical formula C29H34, and one is peri-condensed with the chemical formula C26H30 (Carlson et al., 2007). Irregular catamantanes do not follow the general formula C4n+6H4n+12 Their codes have at least two identical digits separated by any two other digits (excluding parentheses with their contents). Figure 1.4 shows structures of some higher diamondoids. Among the diamondoids of this figure, only [12312] hexamantane and [121321] heptamantane are irregular. Table 1.1 lists some physical properties of diamondoids including their molecular weights, melting points, apparent boiling points, and normal densities.

Fig. 1.4. Some of the higher diamondoids up to heptamantane. All tetramantanes are regular cata-condensed polymantanes. Shown pentamantanes are also regular catamantanes. Peri-condensed [12312] hexamantane (C26H30) and [121321] heptamantane (C30H34) and other higher diamondoids may become fundamental components in nanometric devices (see also Fig. 4.13). Adapted from CDV Diamond Group {www.chm.bris.ac.uk/pt/diamond/diamondoids.htm} 2010.

Diamondoids melt at much higher temperatures than other hydrocarbon molecules with the same number of carbon atoms in their structures. The melting point of adamantane (269°C) is probably the highest among all organic molecules with the same molecular weights. Since diamondoids also possess low strain energy, they are more stable and stiff, resembling diamond in a broad sense. They possess superior strength-to-weight ratio.

It has been found that adamantane crystallizes in a face-centered cubic lattice, which is extremely unusual for an organic compound. The molecule therefore should be completely free from both angle strain (since all carbon atoms are perfectly tetrahedral) and torsional strain (since all C-C bonds are perfectly staggered), making it a very stable compound and an excellent candidate for various applications, as will be discussed later in this book.

At the initial growth stage, crystals of adamantane show only cubic and octahedral faces. The effects of this unusual structure on physical properties are interesting (Kabo et al., 2000).

Many of the diamondoids can be brought to macroscopic crystalline forms with some special properties. For example, in its crystalline lattice, the pyramidal-shaped [1(2,3)4]pentamantane has a large void in comparison to similar crystals (Table 1.1). Although it has a diamond-like macroscopic structure, it possesses weak, noncovalent, intermolecular van der Waals attractive energies that are involved in forming a crystalline lattice (Dahl et al., 2003; Mansoori et al., 2003). Another example is the crystalline structure of 1,3,5,7-tetracarboxyadamantane, which is formed via carboxyl hydrogen bonds of each molecule with four tetrahedral nearest neighbors. The similar structure in 1,3,5,7-tetraiodoadamantane crystal would be formed by I-I interactions. In 1,3,5,7-tetrahydroxyadamantane, the hydrogen bonds of hydroxyl groups produce a crystalline structure similar to inorganic compounds, like cesium chloride (CsCl) lattice (Desiraju, 1996) (Fig. 1.5).

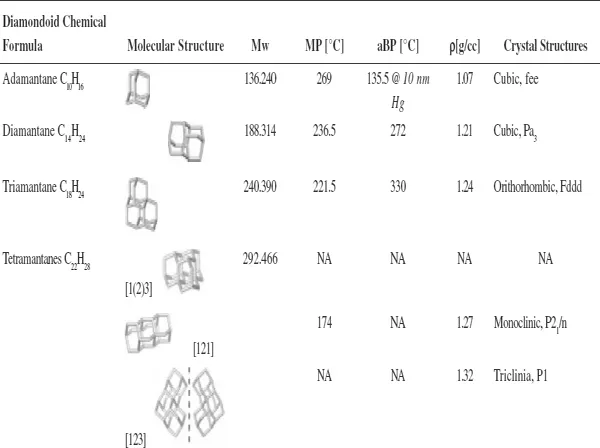

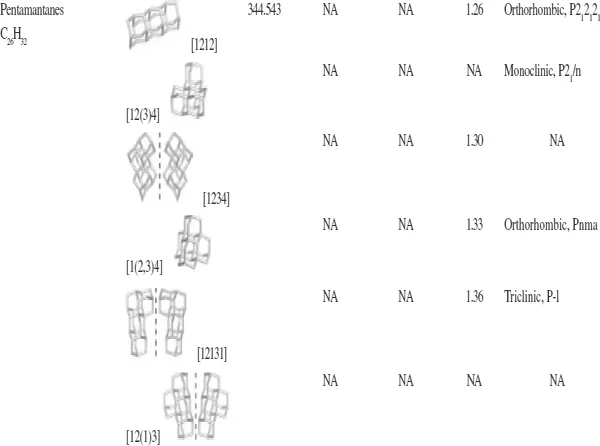

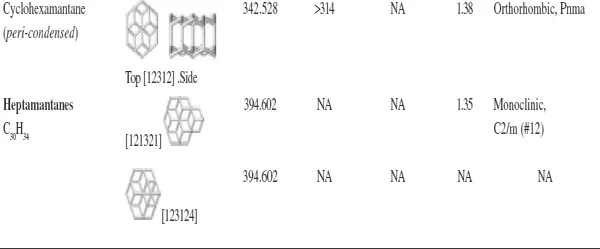

Table 1.1. Some physical properties of diamondoids (Mansoori, 2007).

aBP = apparent boiling point; MP = melting point; Mw = molecular weight; ρ = normal density. Adapted from ChevronTexaco (...