![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Prior to the early 1930s, the researchers were divided for a long period on their view of the nature of the molecules constituting naturally occurring substances, such as cellulose, starch, proteins, and natural rubber, which exhibit unique physical and mechanical properties. 1, 2 These substances or their derivatives form colloidal solutions when dissolved in solvents. For example, in solutions they diffuse very slowly and do not pass through semipermeable membranes. There were two schools of thought. One school held the view that the substances are constituted of colloidal molecules, which are aggregates of ordinary molecules held together by secondary valence forces. 1, 3–6 This primary small molecular constitution found support for some time even in X-ray crystallographic study, which incorrectly interpreted the unit cells of cellulose and of crystallized rubber to be representing the whole molecules. It was held that since the unit cells are similar in size with those of simple compounds the molecules must be small. 7

However, negligible freezing point depressions of the colloidal solutions or some tens of thousands molecular weights determined in some cases, by cryoscopy or osmometry, strongly suggested the alternative view that the molecules are intrinsically big (macromolecules) being comprised of atoms bonded together by normal covalent bonds. Nevertheless, the proponents of the colloidal molecular hypothesis brushed such evidences aside on the unsubstantiated ground that the solution laws underlying the methods would be inapplicable to colloidal solutions. 1

Against this backdrop, Staudinger relentlessly championed the macromolecular hypothesis presenting evidences in support. For example, he demonstrated that the soluble macromolecular substances give colloidal solutions, even when variously derivatized, in whichever solvents they are dissolved. This is very unlike the colloidal associates of simple molecules such as the soap micelles, which disintegrate to yield molecular solutions on making appropriate changes in solvents. In addition, the derivatives have the degrees of polymerization about the same as the original polymer had. He also made extensive investigations with synthetic polymers, polystyrene, and polyoxymethylene, in particular, and suggested chain structures for them as early as 1920. He was also the first to relate intrinsic viscosity of polymer with molecular weight. 2 That the relation was imperfect does not diminish its importance as a step in the right direction. 1

X-ray crystallographic evidences in favor of the chain molecular structure also came along. Thus, Sponsler and Dore interpreted the crystallographic data on cellulose fibers in terms of unit cell, which represents a structural unit of the polymer chain rather than the whole molecule. 8 However, this interpretation based on rather limited data was not fully correct in being incompatible with the chemical evidence of cellobiose as the repeating unit. 10 The correction was subsequently done by Meyer and Mark who successfully applied the crystallographic method to establish the chain structures also of silk fibroin, chitin, and natural rubber. 9

It must not be understood that these are the only work, which won the case for the macromolecular hypothesis. There were several other work, which also contributed. 1, 10 The foremost of these are the work of Carothers, which we shall be acquainted with later in this and next chapter. 11 For the present, we shall be content with learning that Carothers was the first to formulate the principles for synthesizing condensation polymers and predicting their molecular weights. The successful application of these principles left no room for doubting the chain molecular nature of polymers.

However, while the term ‘macromolecule’ points to the big size of the molecule, the term ‘polymer’ not only connotes macromolecule (although Berzelius first used the term naming butene a polymer of ethene 10), but also reflects the manner how it is built up. Derived from Greek words ‘poly’ meaning ‘many’ and ‘mer’ meaning ‘part,’ polymer (= many parts) means a molecule built up of many units (parts) joined. The small molecules, which are the precursors of the units, are called ‘monomers’ –‘mono’ meaning ‘one’. Sometimes the terms ‘high polymer’ and ‘low polymer’ are used to emphasize the big difference in molecular weights between them.

Before 1930, high polymeric materials used commercially were the naturally-occurring types or their derivatives, e.g., cellulose, silk, wool, rubber, regenerated cellulose, cellulose acetate, nitrocellulose, etc., the only exception being Bakelite, a phenolic resin, patented by Baekeland in 1909. However, no sooner had the macromolecular hypothesis gained ground than a rapid growth of synthetic polymer industry ensued. Thus, within ten years beginning 1930 many of the commodity polymers came into industrial production: poly(vinyl chloride) (1930), poly(methyl methacrylate) (1935), polystyrene (1935), low density polyethylene (1937), nylon 66 (1938), and nylon 6 (1940).

1.1 Nomenclature

The most widely used nomenclature system for polymers is the one based on the source of the polymer. When the polymer is made from a single worded monomer, it is named by putting the prefix “poly” before the name of the monomer without a space or a hyphen. Thus, the polymers from ethylene, styrene, and propylene are named polyethylene, polystyrene, and polypropylene respectively. However, when the name of the monomer is multiworded or abnormally long or preceded by a letter or a number or carries substituents it is placed under parenthesis, e.g., poly(vinyl chloride), poly(ethylene oxide), poly(chlorotrifluoroethylene), poly(∈-caprolactam), etc. For some polymers, the source (monomer) may be a hypothetical one, the polymer being prepared by a modification of another polymer, e.g., polyvinyl alcohol). The vinyl alcohol monomer does not exist; the polymer is prepared by the hydrolysis of poly(vinyl acetate).

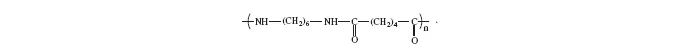

In the above examples, a single monomer forms the repeating unit of the polymer (vide infra). However, many polymers exist in which the repeating units are derived from two monomers. Such polymers are named by putting the prefix “poly” before the structural name of the repeating unit placed within parenthesis without a space or a hyphen. Thus, the polyamide with the repeating unit derived from hexamethylenediamine and adipic acid is named poly(hexamethylene adipamide),

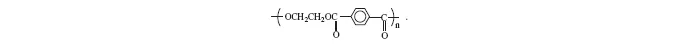

Similarly, the polyester with the repeating unit derived from ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid is named poly(ethylene terephthalate).

However, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry have developed a detailed structure-based nomenclature. 12a, 1 In this book, we shall follow the commonly used source-based nomenclature described above.

1.2 Structural and Repeating (or Repeat) Units

Polymers are identified by the structural and repeating units in their chain formulae. A structural unit (or “unit” in short) in a polymer chain represents a residue from a monomer used in the synthesis of the polymer, whereas a repeating unit, or a repeat unit, refers to a structural unit or a covalently bonded combination of two complementary structural units, which is repeated many times to make the whole chain.

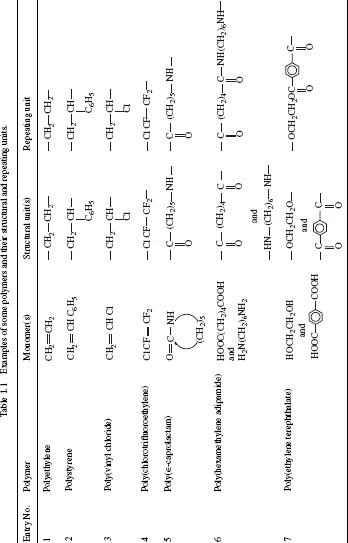

The structural and repeating units are identical when a single monomer is used in the preparation of the polymer but not so when more than one monomer is used. Examples are given in Table 1.1. In each of the first five examples in the table, the repeating unit has only one structural unit, whereas in the last two examples the repeating unit in each case is composed of two covalently bonded unlike but complementary structural units.

1.3 Classification

1.3.1 Condensation and addition polymers and polymerizations

Carothers classified polymers into two groups, condensation, and addition. In condensation polymer, the molecular formula of the structural unit is devoid of some atoms from the ones present in the monomer(s) from which the polymer is formed or to which it may be degraded

by chemical means. In contrast, in addition polymer, the molecular formula of the structural unit is the same as that of the monomer from which the polymer is formed. 11, 13

By way o...