- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Scientific Writing: A Reader and Writer's Guide

About this book

Check out the author's website at www.scientific-writing.com

Given that scientific material can be hard to comprehend, sustained attention and memory retention become major reader challenges. Scientific writers must not only present their science, but also work hard to generate and sustain the interest of readers. Attention-getters, sentence progression, expectation-setting, and “memory offloaders” are essential devices to keep readers and reviewers engaged. The writer needs to have a clear understanding of the role played by each part of a paper, from its eye-catching title to its eye-opening conclusion. This book walks through the main parts of a paper; that is, those parts which create the critical first impression.

The unique approach in this book is its focus on the reader rather than the writer. Senior scientists who supervise staff and postgraduates can use the book to review drafts and to help with the writing as well as the science. Young researchers can find solid guidelines that reduce the confusion all new writers face. Published scientists can finally move from what feels right to what is right, identifying mistakes they thought were acceptable, and fully appreciating their responsibility: to guide the reader along carefully laid-out reading tracks.

Contents:

- The Reading Toolkit:

- Require Less from Memory

- Sustain Attention to Ensure Continuous Reading

- Reduce Reading Time

- Keep the Reader Motivated

- Bridge the Knowledge Gap

- Set the Reader's Expectations

- Set Progression Tracks for Fluid Reading

- Create Reading Momentum

- Control Reading Energy Consumption

- Paper Structure and Purpose:

- Title: The Face of Your Paper

- Abstract: The Heart of Your Paper

- Headings/Subheadings: The Skeleton of Your Paper

- Introduction: The Hands of Your Paper

- Introduction Part II: Popular Traps

- Visuals: The Voice of Your Paper

- Conclusion: The Smile of Your Paper

Readership: All scientists for whom the “publish or perish” saying applies, whether in academia or in companies engaged in research activities, and postgraduates writing dissertations or theses.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Part I

1

- If an acronym is used only two or three times in the entire paper, it is better not to use one at all (unless it is as well known as IBM).

- If an acronym is used more than two or three times, expand its letters the first time it appears on a page so that the reader does not need to flip pages back and forth. Some journals ask authors to regroup all acronyms and their definitions at the beginning of their paper so that the reader can locate them more easily.

- Avoid acronyms in visuals or define them in their caption.

- Avoid acronyms in headings and subheadings because readers often read the structure of a paper before going inside the paper.

- Be conservative. Define all acronyms, except those commonly understood by the readers of the journal where your paper is published.

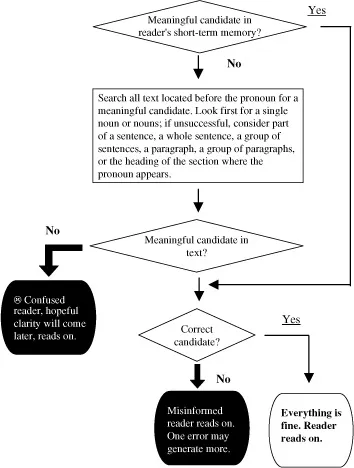

- If you point in the direction of someone who has already left the room, nobody will understand. Likewise, if the noun the pronoun points to is 20 or 30 words back in the text, it may have left the reader's short-term memory; the noun–pronoun link is broken. Usually, this memory lapse is not enough to discourage readers from reading forward. They tolerate ambiguity and read on because they are hopeful that the text will become clearer later. Interpretation errors and reduced understanding are therefore likely.

- If you point towards a person in a group far away from you, people will find it difficult to guess whom exactly you are pointing to. When the pronoun points back to several likely candidates, the reader—whose incomplete understanding of the text does not allow disambiguation—will pick the most likely candidate and read on, hoping clarity will be forthcoming. If that likely candidate is the wrong one, then interpretation errors will follow and understanding will drop to a lower level.

- Finally, some fingers seem to point nowhere; actually, they point somewhere, but only the person who is pointing knows where. When the pronoun points to something that is only in the mind of the author, the reader is left guessing and more often than not guesses wrongly. Understanding thus drops to a lower level.

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface Page

- Contents

- Part I - The Reading Toolkit

- Part II - Paper Structure and Purpose

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app