![]()

CHAPTER 1

SEA CHANGE IN THE INDIAN ECONOMY

Jayashankar M. Swaminathan†

As the clear blue waves from the Arabian Sea splashed on the walls of Fort Aguarda, which had been turned into a nice five-star hotel, the bollywood music from the beach boy's transistor brought me to the realization that I was indeed in India. This was the summer of 2004, and I was in Goa with 25 MBA students from the Kenan-Flagler Business School at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. Our time in Goa was a short break for us in-between our hectic 10 days in Delhi, Mumbai, and Bangalore studying top firms in India and the challenges and opportunities of doing business there. This was our first year in India. This trip has subsequently become an annual pilgrimage for me, to learn more about the Indian economy and to impart that knowledge to a group of future global managers.

Interestingly, during our visit to India in 2004 there were several times when I temporarily forgot that I was in India because of the surrounding environment that would often resemble and sometimes exceed that in the developed world—while we were visiting the Network Operating Center at Reliance in Mumbai (now Reliance Infocomm) and the Failure Detection Center at Power Grid Corporation in Delhi; while observing the manufacturing excellence at Hero Honda in Gurgaon and Intimate Apparel in Bangalore (MAS Holdings); and also while visiting the software development facility at Infosys in Bangalore and call center operations at Wipro BPO in Delhi (formerly Wipro Spectramind). This experience was not only limited to corporate environments but extended to day-to-day activities, while shopping at the extravagant malls in Delhi and Mumbai, observing the in-flight service and baggage handling of JetAirways, and (during another visit earlier that year) leading a classroom discussion at the Indian School of Business in Hyderabad. In each of these situations my expectations were far exceeded.

Fig. 1.1. Map of India.

During the next four years several more trips back to India provided me the opportunity to closely interact with outstanding individuals from firms such as the Reliance Group of Industries, Ranbaxy, Aditya Birla Group, TVS Motors, ICICI Bank, GMR, HCL, Maruti, Mahindras, Godrej, Shoppers Stop, Kingfisher Airlines, Brickworks, and Evalueserve, among others. I have sensed a great deal of passion and energy and the drive to excel during my conversations not only with corporate executives but also with engineers, investment bankers, bureaucrats, and even the country's politicians.

A sea change is taking place in India today. Just like the sea, from a distance the Indian economy appears to be calm and smooth. However, there are rapid and turbulent changes happening at the very core of the Indian business economy whose power and energy are not perceived till one experiences and studies it carefully.

1.1. Earning and Spending More than Parents

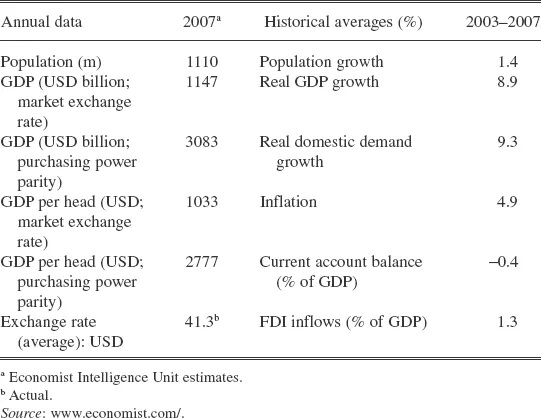

Table 1.1. Snapshot of Indian economy.

First and foremost, the economy has been growing at an amazing rate: more than 7% annually on average over the last decade. According to the World Bank, India is on track to record a growth rate of approximately 9% in 2007 (Table 1.1).4 This makes India the second fastest-growing economy in the world after China. Although the projections are that the Indian economy is slowing to an extent and will be growing at only 7.5% by 2012, this is still a very fast growth pace. Optimistic estimates, such as those by Goldman Sachs, predict that India's GDP will reach USD1 trillion by 2011, USD2 trillion by 2020, USD6 trillion by 2032, USD10 trillion by 2038, and USD27 trillion by 2050. That would make India the third-largest economy in the world after the United States and China. In this projection, India's GDP will overtake Italy's by the year 2016, France's by 2019, the United Kingdom's by 2022, Germany's by 2023, and Japan's by 2032. India's current GDP based on market exchange rates is already at USD1.14 trillion.6

India's economic growth over the last 20 years has been triggered by the knowledge-based service sector, particularly services related to information technology and business process outsourcing (BPO). As a result, the Indian economy, which in 1990 had a GDP split of 15%, 43%, and 30% among the manufacturing, service, and agriculture sectors, respectively, had changed to 15%, 52%, and 22% by 2003.9 Over the last four years, the manufacturing sector has also grown quite well in some fiscal quarters, outpacing the growth in services, so that the latest split among these sectors is roughly 16%, 54%, and 17%, respectively.4

Fig. 1.2. Affluent Indians are driving consumer spending.

Much of this growth in the Indian economy has benefited the burgeoning economic middle class, which now comprises over 200 million people. It is important to remember that the middle class in India does not earn the same amount as the middle class in the developed world. A household income of roughly USD5000 qualifies one to be in the middle class in India, while the same status requires closer to USD45,000 in developed countries. Still, the overall purchasing power of the Indian consumer market is quite large. Today's young Indian middle class earns much more than the previous generation (their parents), and due to Indian culture many of these young workers continue to live with their parents even after getting a job, giving them more disposable income on hand. This is one reason that India has been witnessing a consumer spending boom (Fig. 1.2). In 2003, the Indian retail market was estimated at USD250 billion, which put it in the top 10 countries in the world. This market is projected to reach USD400 billion by the year 2010, which would place India in the world's top five retail markets. This growth has had a tremendous impact on many sectors. One such sector is mobile phones: India adds 5.5 million new subscribers every month, according to iSupply. In 2006, the number of subscribers in India reached 149.5 million, and that number is projected to grow to 484 million by 2011. In the same year, 69.3 million new handsets were sold to Indian consumers, making India the second biggest market after China.7 To put this in perspective, this is roughly equivalent to every fifth adult or child living in the United States buying a new cell phone every year.

1.2. Collaboration in Infrastructure Development

Whenever the Indian economy is discussed in any forum, very soon the focus turns to the fact that India lacks standards for the infrastructure of basic amenities such as power, water, and transportation. For decades, the Indian government and politicians have talked about improving these, but very little was seen in terms of actual action. Today, there is a sense of urgency among business and political leaders about the improvement of India's infrastructure. My conversation with Mr. Chandrababu Naidu,a former Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, clearly indicated that the government, as much as the private sector, realizes that infrastructure improvement is one of the keys to economic development in India. Such a focus has led to some outstanding achievements on this front in the last few years.

The Golden Quadrilateral project,b valued at USD12 billion, connects India through more than 3000 miles of expressways running from Delhi (in the north) to Kolkata (in the east) to Chennai and Bangalore (in the south) to Mumbai (in the west) and back to Delhi. This initiative was started by the Bhartiya Janata Party during its tenure and was continued by the Congress and Alliance parties after they took office in 2005, and it is now almost complete. On a recent visit to India, I was astonished by the speed and relative ease with which one could travel from Chennai to Bangalore by road, which 25 years ago could only have occurred in a dream. The Delhi Metrorail, which was started in 2002 with just 8.5 kmc of track, has been a tremendous success over the last five years. Phase I of the project, with 65 km of track, was completed on time in 2005, and Phase II of the project, which is currently underway, is expected to have 121 km of its route completed by 2010. On a busy day, the Delhi Metrorail has the capacity to carry 650,000 passengers, and it is expected to expand to a capacity of 2.6 million passengers by 2010. Following up on Delhi's success, several other major cities in India are planning to build metro-rails as well. Last year, I had the opportunity to visit the greenfield international airport being built at Hyderabad (Fig. 1.3). The airport was expected to have an initial capacity to handle 12 million passengers per year, subsequently expanding to about 40 million passengers per year. This international airport, with several state-of-the-art features, was completed on time in March 2008, something unique worldwide as far as infrastructure projects are concerned. It is a public-private partnership between the GMR group, the Malaysian Airport Holdings Berhard, the state government of Andhra Pradesh, and the Airport Authority of India. This public-private collaborative model is being replicated at other airport projects across the country.d

Fig. 1.3. Rajiv Gandhi International Airport in Hyderabad.

1.3. Going Beyond Software and Information Technology

There have been a number of books that highlight India as a prime offshore destination1,2—a place where firms can outsource most of their difficult or routine tasks, such as software maintenance and technical helpdesk services. Bangalore is considered the Silicon Valley of India, where most of the multinationals in the high-tech industry as well as some of the largest Indian software firms such as Infosys, Wipro, Tata Consultancy, and Hindustan Computers Limited (HCL) are located. Clearly, this is an area in which Indian firms have gained a lot of ground over the last 15 years. For example, a recent advertisement by the Government of India indicated that 50% of the Fortune 500 firms have outsourced their information technology operations to India.

Although for a novice, India is mostly about outsourcing technology-related activities, there are other significant things happening today in other industries as well. The big successes in the software and BPO sectors at the international level have imbued business leaders and managers in other industries with the confidence that they too can excel on the world stage. Some firms such as Reliance Industries are already world leaders. Reliance is the world's largest producer of polyester fiber and yarn, one of the top 10 producers of chemical components such as paraxylene, polypropylene, and purified terepthalic acid. Several other Indian manufacturing firms, in their aspiration to become worldwide leaders in their industries, are taking the acquisition route. In March 2008, Tata Motors signed a deal to acquire the Jaguar and Land Rover brands from Ford Motors. In 2007, Tata Steel acquired Corrus, making it the fifth-largest steel producer in the world, while Aditya Birla Group's Hindalco acquired Novelis, which made it the world's largest aluminum rolling company. The previous year, Mittal Steels acquired Arcelor to become the biggest worldwide producer of steel. Ranbaxy, India's largest pharmaceutical company, acquired Ethimed in Belgium, Terapia in Romania, and the unbranded generic business of Allen SpA of Glaxo Smith Kline in Italy. Recently, Bharti Airtel and Reliance Communications, India's two largest wireless provider have shown interest in acquiring a stake in MTN wireless in South Africa. More recently, Sterlite Industries announced that it plans to acquire the copper mining assets of Arasco in the United States for USD2.8 billion. It is no surprise that when the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) published the recent list of top 100 emerging multinationals from the rapidly developing economies of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Egypt, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Thailand, and Turkey, India—with 20 companies on the list—was second only to China. These firms are creating exciting new innovations for the world.

One of these innovations is the Nano car, introduced by the Tata Motors earlier this year. The four-door Nano is a little over 10-feet long and nearly 5-feet wide. It is powered by a 623cc two-cylinder engine at the back of the car. With 33 horsepower, the Nano is capable of traveling up to 65 miles an hour. Its four small wheels are at the absolute corners of the car to improve handling, and it has a small trunk, just big enough for a duffel bag. The Nano will go on sale in India later this year for USD2500, with an initial annual production run of 250,000. When plans for this car were unveiled a few years ago, almost no one in the industry could believe that it could be manufactured at this price. Tata says that it will offer the Nano in other emerging markets in Latin America, Southeast Asia and Africa within four years.5 This is just the tip of the iceberg as far as Indian manufacturing is concerned. Many of the firms on the Boston Consulting Group list will go on to challenge existing multinational firms, but there are many other outstanding firms in India that are not yet on that list, and they are equally hungry to join the world stage in their industries. In the upcoming years, we are likely to witness a change in which India will come to be known for something much more than just being a great location for offshoring tech services.

1.4. Young, Educated, and Motivated Workforce

India is the second-largest country in the world in terms of population and is expected to overtake China sometime in the first half of this century. It is interesting that more than half of the population is under 25 years of age. In comparison, that same percentage is about 40% for China, 30% for the United States, and 25% for Germany. It is true that many in the Indian population are very poor by international standards, but roughly one-third of India's population is in the lower middle class or above. This translates into 350 million people that are eager for success, about 175 million of whom are less than 25-years old. These young men and women have witnessed the growth of multibillion dollar companies such as Infosys and Reliance, both of which were started with personal finances and loans by motivated, bright, and hard-working individuals from the middle class who sought the right opportunities at the right time. They have also heard great success stories about their uncles, aunts, and distant relatives who emigrated from India and now are a part of a vibrant and successful Indian community in different parts of the world, including the Middle East, Malaysia, Singapore...