![]()

Part I

Content Selection

Executive Summary

Content selection is guided by six criteria:

1) The expectations of people who directly or indirectly contributed to your work

2) The technical background required by an “imperfect” audience to follow your presentation (i.e. an audience in the same domain, but not expert in your field)

3) The expectations created by the keywords in the title of your talk

4) The novel or useful information that can be presented and understood quickly

5) Novel or useful information at a level of detail such that it convinces the audience to read your paper for more in-depth information

6) The task (either yours or that given by your management) to be accomplished via your presentation such as hiring, being hired, or securing funding

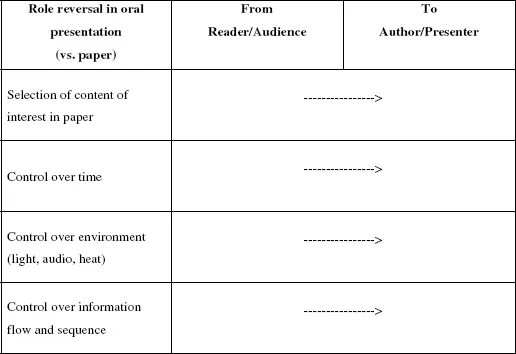

Listening to an author’s oral presentation of his/her paper is inherently different from reading that author’s paper (Fig. 1). The net effect of the difference is a transfer of responsibilities from the reader/audience (the information consumer) to the presenter/author (the information producer).

Fig. 1. The role of the presenter of a paper has expanded significantly compared to the role of the author of a paper. The audience is now less active, less “in control” than the reader. It has lost some of its prerogatives and initiatives.

![]()

1

PAPER AND ORAL PRESENTATION: THE DIFFERENCE

Compression exercise

Vladimir looked at his paper and uttered a deep sigh. Distilling twelve months of work into an eight-page paper was hard enough, but cutting his work down to fifteen slides was near impossible. He had so much significant data, so many formulas, figures and tables to present. He loved mathematics and was very good at it. He would dazzle the audience by moving from one complex formula to another with the greatest of ease. Therefore, he decided to keep them. He was also very good in modelling, and used complex but accurate numerical analysis methods neglected by other scientists. He would spend some time explaining the methodology, and the algorithms. That way, the results would make more sense, he thought. He scrolled down the pages to the results part of his paper and looked at his twelve figures. He needed to bring these into his presentation, but they would occupy at least three quarters of his fifteen slides. That was too many for his liking. He grabbed his chin and pinched it while thinking of a way to make them fit in less slides.

“What if I merged these two figures into one by adding a right vertical axis to the XY diagram to turn it into a XYY’ diagram since both figures share the same X axis. Um, alternatively I could also shrink the visuals and put two on one slide.” Vladimir was unsatisfied. He was convinced there was a better way. Suddenly, he found it! Instead of using figures, he would go back to the original data and put them inside several large tables that would fit in less slides.

“Yes! That will work!”

He felt very pleased with himself. The challenge of squeezing his large paper into a few slides no longer looked so formidable.

“Hey,” he thought, “maybe there is also a way to present my formulas.”

His mathematical and analytical skills could surely be applied to this greater challenge. He looked back to the methodology section of his paper, the one with the Navier Stokes equations written in the Eulerian Lagrangian formulation and thought…and thought…Somehow, presenting these formulas was not as easy as presenting data because there was a lot of text describing them. He used his finger to count the number of coefficients: alf , atf , c, Ct, f, h, h0, hlf , htf , k, t, t0, Re, St, u, U, xi, xfc, xlf , xtf . There were 20 of them. He thought about shrinking down the size of the formulas but the subscripts would not be very readable. Hmm…He pinched his chin a little harder.

“Maybe I could just skip some formulas and tell the audience to read about them in the Kim and Choi 2002 paper…No, that would not be good.”

Suddenly, he smiled and snapped his fingers as his brain shouted a silent eureka.

“I will use one slide to write down the definition of all coefficients, and another slide to write the formulas.”

Vladimir smiled. Another problem solved by the mighty brain of the great Doctor, he thought.

The Spoken Word vs. The Written Word

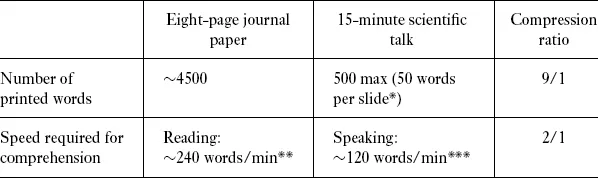

Poor Vladimir! Squeezing an eight-page scientific paper inside a 15-minute scientific talk is an Herculean task (Fig. 1.1). Just consider the physiological reasons:

At the rates given in Fig. 1.1, assuming one reads the whole paper, 45 minutes would be necessary to finish reading. This excludes the time necessary for the explanation of figures and tables. Let’s say explaining them takes another 15 minutes, bringing the total time to one hour. For a fifteen-minute oral presentation, a conservative compression ratio would be 4 to 1. This means that three words out of four have to be taken away when one goes from the written word to the spoken word. The compression ratio gets worse and exceeds 9 to 1 if one takes into account the restricted number of slides, and the restricted number of words one can write on one slide given the font size required to keep text readable on a projection screen. Vladimir is facing an impossible task. Cutting eight words out of nine is not cosmetic surgery. It is butchery. Cutting the fat (the details) is insufficient. One has to cut into the meat and into the bone and yet keep enough detail to convince others of a scientific contribution. Put as an information/time compression challenge, the problem seems intractable. Fortunately, the solution is not to be found in some optimisation scheme, but in “the inherent difference that exists between oral and written communication”.

Fig. 1.1. Compression factors to be considered to go from an eight-page written paper to a fifteen-minute presentation.

* Assumed here are one and a half minute per slide, a reasonable estimate given the time needed to explain the many visuals typically found in a scientific presentation. Beyond 60 words per slide, two unwanted side effects occur: 1) readability at a distance is greatly curtailed and 2) the audience starts reading instead of listening to the presenter.

** Observed over several thousand scientists with English as a second language (most probably auditory readers). English native speakers do better but, in a formal presentation, you have to give time to the non-English native speakers to read.

*** Speaking speed for conversational English is actually higher (165–180 words per minute). However, a formal presentation is not a conversation. The pace has to be slower to ease comprehension (particularly for a scientific presentation to an international audience, or from a presenter with a strong accent).

Intuitively, all agree there is an inherent difference but then again, there is also so much resemblance between the two. A paper is read. Shouldn’t slides be read also? A paper has a standard structure that follows the scientific process from observation to hypothesis, methodology, results and discussion. Shouldn’t a presentation follow the same structure? A paper contains sufficient detail to allow the reader to verify the claim independently. Shouldn’t a presentation enable the audience to verify the claim? A paper presents facts in an objective, impersonal way to the reader. Shouldn’t a presentation remain impersonal?

I discovered that the answer to these questions turned out to be a resounding NO. Why? Let us review these inherent differences.

The first inherent difference is in front of Vladimir: the audience. It is not miles away in another continent, reading his paper; it is right in front of him. Some people even attend his presentation for reasons other than to find out about his scientific contribution. Let’s find out. Come with me inside the conference room and let us sit together on the last row next to the exit door where we have a good view of everyone entering and leaving.

Blinded

Vladimir is now behind the lectern. The notebook on the narrow ledge of the lectern in front of him displays the same slide as the large screen behind him, his title slide. The chairperson sitting at a low table to his right is reviewing the notes on Valdimir’s profile before the formal introduction. Vladimir uses these few seconds of silence to glance at the audience. There are about a dozen people in the room. Three are sitting in the last rows, ready to make a fast exit.

Two are sitting next to one another.

Everybody else sits alone, mostly at the end of a row by the aisle, conference bag conveniently placed on the adjacent seat, preventing anyone to sit close by.

His manager sits in front of him in the second row.

A senior person sits in the middle of the room, directly facing centre screen. Vladimir is distracted by the entrance of a younger woman in a pale blue blouse that matches the darker blue of the conference badge holder clipped to the large buckled belt of her jeans. She picks a seat on the second row, not far from his manager who turns his head to look at her longer than he had planned to.

She is followed a few seconds later by a middle-aged man in suit and tie, the managerial type. As he walks down toward the front of the room, he notices the elderly person in the middle row and sits next to him.

They smile at each other and exchange a few discrete words. Had Vladimir been able to hear their conversation, he would have heard the following dialogue:

“Hi Bill, fancy seeing you here. What brings you to this talk?”

“Hi Chris. We sponsored Dr. Toldoff’s research. That’s why I’m here”.

“Is he asking you for additional funds?” Chris asks.

“Don’t they all…” He grins and asks “And what brings you here Chris?”

“I’m head hunting for my lab at Cornell. Dr. Toldoff’s work is of interest to us. I’m checking to see whether Dr. Toldoff himself is also of interest to us. Would you transfer his NSF extension grant to our lab if we were to hire him?”

“It is worth a thought,” Bill replies.

“No, it’s worth millions!” Chris counters laughing.

The laughter attracts the attention of Vladimir who wonders who these two important-looking people are and why they came to his talk. The introductory words of the chairperson interrupt his thoughts.

Collective Audience but Individual Expectations

Some expectations are common to any audience, others are specific to a scientific audience, and others still are of a personal nature. For example, the sponsor of Vladimir’s research is certainly expecting to see the name of his organisation mentioned on the slides (and that is only one of his many expectations). Let us look at the audience Vladimir faces and learn about their expectations. There are twelve people scattered in the room.

• Prof Christopher Mitchell-Untak, head of the speech lab at Carnegie Mellon University, reviewer of Vladimir’s paper, hunting for new hires

Hi, call me Prof MU, my researchers do; I am the one who reviewed Dr. Toldoff’s paper. Quite interesting research at the border betwee...