![]()

Why do Many Other Scientists Believe Time Began at a Big Bang?

Our everyday perception of the universe comes from looking up at the sky to see the Sun in the daytime and, more profoundly, to see thousands of stars in the night sky. Surely some of the oldest questions since the beginnings of human thought are: How large is the universe? Did it ever begin? What are the principal constituents of the present universe? Will time ever end?

Cosmology is the name for the scientific study of the universe. The present time is an unprecedented age for cosmology because it is fair to say that in the last twenty years we have learned more in cosmology than in all of previous human history. Despite this enormous and exciting growth of our knowledge as a result of many impressive observations, the universe has become more enigmatic in many ways. The more we learn, the more the extent of our ignorance becomes manifest.

Cosmology has recently answered some of the old questions and in this chapter we shall give answers to the first two: How large is the universe? How long ago did it—at least the present expansion era—begin? We can all agree that the expansion stage we are presently in began a finite time ago but, as I shall explain later in this chapter, it is not obvious that time itself began then, if ever.

We do know how large the visible universe is, meaning how far away the most distant galaxies are whose light can reach us on the Earth. It is theoretically possible, and even favored in some theoretical scenarios, that our universe is actually much larger than the visible universe. In some very speculative scenarios the universe is spatially finite with non-trivial topology. This is at present not readily testable so we shall be content to try to convey just how gigantic the visible part is.

The observational means by which we know accurately the size of the universe will not concern us here but it is sufficient to say that present studies using the Hubble Space Telescope combined with the largest (up to 10 meters in diameter) ground-based optical telescopes tell us the size of the visible galaxy to an accuracy of a few per cent. This sort of accuracy has been achieved only since the turn of the 21st century.

Cosmological distances are so much bigger than any distance with which we may be familiar, it is not easy to grasp or comprehend them even in our imagination. So let us begin with the largest distance which is easily comprehensible from the viewpoint of our experience.

A very long airplane ride may take 15 hours and go 9000 miles, a significant part of halfway around the Earth. People who travel a lot may take such a flight a few times each year. One knows that the plane has a ground speed of about 600 miles per hour and the discomfort of sitting, especially in economy class, for such a long time gives a strong impression of just how far that distance is. Of course, people a hundred years ago would never travel that far in a day but now we do and it gives us a feel for the size of the planet so that makes it a length distance from which we can begin.

The next larger distance to think about is the distance between the Earth and the Moon. This is about thirty times the distance of the plane ride and so it would take equivalently some three weeks at the same airplane speed, or a few days in a NASA spacecraft. The distance to the Moon is thus imaginable: if you walked at four miles an hour non-stop without sleep it would take about eight years to arrive and another eight years to return. Nevertheless, the arrival on the Moon of astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin in July 1969 was one of the most memorable events of the last century. Only in part was it due to the distance to the Moon, it was equally due to the concept of humans walking for the first time on an astronomical object other than the Earth.

The Moon is visible in the night sky, and just as often present in the daytime thanks to its reflection of light from the Sun. The Sun is by far our nearest star and its radiated energy is crucial to the possibility of life on Earth. How far away is the Sun? It is about ten thousand times the length of the airplane ride and would take about twenty years to reach at the speed of an airplane. Not that any sane person would want to go there with a surface temperature well above that of molten iron. The Sun is about four hundred times further away than the Moon, and is already at such a large distance that it far exceeds anything with which we are familiar. This sets the scale of the Solar System with the Earth, rotating on its axis once a day, orbiting once a year around the Sun at a distance of some ninety-three million miles. Other planets like Mercury and Venus, circulate inside the Earth's orbit while six others including Mars, Jupiter and Saturn orbit outside the Earth.

It is almost inconceivable that any human being will travel outside of the Solar System in our lifetimes because of its enormous size. Yet on the scale of the visible universe, the Solar System is, in contrast, unimaginably tiny and insignificant. If there were no life other than on the Earth the universe would seem to be an absurdly large object if life were its primary goal.

In addition to the Moon and some planets, we can see thousands of stars with the naked eye. Most of these stars are similar to our Sun but appear much dimmer because of their distance from us. How distant are even the nearest stars? The answer is some two million times the distance to the Sun. So whereas we can reach the Sun in twenty years at the speed of an airplane, to reach the nearest star in twenty years would require a two million times faster speed. A quick calculation shows that this takes six hundred miles per hour into thirty-five thousand miles per second. To put such a speed into perspective, the speed of light is about one hundred and eighty thousand miles per second. This means our imaginary airplane, suitably coverted as a spacecraft, must travel at one fifth of the speed of light just to reach the nearest star in twenty years.

Here we see the limitations to any travel possibilities not only in our lifetime but what would seem to be forever. According to the theory of relativity, which there is no reason to doubt, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light. So even if the human lifetime is extended by medical advances to two hundred years or even a thousand years, it is impossible to travel during one lifetime to more than a few hundred times the distance to the nearest star. But the galaxy to which our Solar System belongs extends about ten thousand times the distance to the nearest star. So it would seem impossible ever to leave our particular galaxy—known as the Milky Way from its appearance spreading across the night sky.

There are however a couple of holes in this argument. First, according to relativity, time slows down as one travels when approaching the speed of light. Second, it is conceivable that some cryogenic method might be devised to slow down the speed of life and greatly enhance the effective human lifetime. Even so, to travel outside our galaxy does seem forever impossible and cosmology may remain just a spectator sport.

One hundred years ago it was generally believed that the the universe was comprised of only the Milky Way. The size of our galaxy is only ten thousand times the distance to the nearest star and already that is two hundred thousand times the distance to the Sun. Therefore, the galaxy size is two billion times (one billion is a thousand million) the Earth-Sun distance. The size of the galaxy seems to be relatively independent of time and so in ignorance of a universe very much bigger than a single galaxy, it was believed before the 1920s that the universe itself was static, neither expanding nor contracting.

When the General Theory of Relativity was proposed in 1915, this state of the observational knowledge stymied what could have been predicted, namely, the overall expansion of the universe. This expansion, which is a key feature of the universe and will lead us to the conclusion that it had a definite beginning, became an option only by observations somewhat later during the 1920s.

Now we arrive at the final leap in the distance scale. The visible universe turns out to be about four hundred thousand times the size of the Milky Way, very much larger than previously imagined. That is, not only is the Solar System of neglible size with respect to the universe but so is the entire Milky Way. In fact, in theoretical cosmology galaxies are treated as point particles. And the human race may be confined forever to be within one of these points!

We have seen that the size of the galaxy is tremendously larger, by a factor of billions, than the distance to the Sun. And then the visible universe is yet again so much larger than a galaxy that to study it each galaxy may be regarded as just a single dot within it. This should communicate in so many words an idea of just how big the visible universe is. Now we will show how we know that the present expansion (and possibly time itself) had a beginning some fourteen billion years ago.

As has already been discussed, the size of the Milky Way has not expanded by even one order of magnitude since it was formed some ten billion years ago. Within the Milky Way the Sun and the Solar System appeared about five billion years ago. The Earth is a little younger, about four and a half billion years old. The point is the general arrangement of the Sun and planets in the Solar System has not markedly changed in the last few billion years. During that time we may regard the galaxy and its contents being of a constant size.

A truly astonishing revelation comes when we study the same question for the entire universe, including hundreds of thousands of the billions of galaxies outside of the Milky Way. The issue is: what is their typical motion relative to our galaxy?

Here it is important to understand a phenomenon well known in physics called the Doppler effect. It is a more familiar phenomenon for sound waves than for light. When a train blows its whistle and passes a listener the pitch of the whistle falls from a higher note to a lower note. In fact, not only the whistle but the entire train's noise exhibits the same Doppler effect. Why does this happen? It is because the motion of the train towards the listener compresses the sound waves to become a shorter wavelength and, because the velocity of sound is unaltered, to a higher frequency. Similarly, when the train is moving away the sound waves are stretched and the frequency lowers. The pitch for a stationary train would lie between the two pitches of the train approaching and receding. The shift in frequency is calculable simply in terms of the ratio of the speed of the train and the speed of sound.

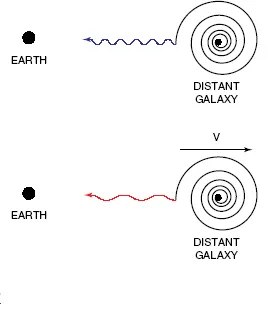

Exactly the same Doppler effect occurs for light. If a galaxy is approaching our galaxy, its light appears with a higher frequency. For the visible spectrum the highest frequency is for blue light so we may say that the light is blue-shifted. On the other hand, if the galaxy is receding from ours its light appears shifted to a lower frequency and is red-shifted toward the red or lowest frequency end of the visible spectrum.

DOPPLER EFFECT: Wavelength of light from distant

galaxy lengthened (red shifted) by speed of recessan

from Earth

In fact, what are observed are the spectral lines of light emitted from known atoms and whose frequencies are accurately known here on Earth. If all the lines are systematically shifted towards the blue then the galaxy hosting these atoms is approaching the Milky Way: if toward the red then it is receding from us. This can be made precise by a mathematical expression for the frequency shift which gives the approach or recession speed as a fraction of the speed of light.

When this is studied for a large number of galaxies it might be expected that roughly half would be blue-shifted and half red-shifted if the overall universe were static and the galaxies were moving randomly.

What was observed, however, to the astonishment of Hubble and Einstein in 1929 is that almost all galaxies are red-shifted. Apart from a few galaxies in our immediate neighborhood like the nearby Andromeda galaxy all the hundreds of thousands of more distant galaxies measured are receding from us. This means that the entire universe is expanding and the galaxies are moving away from us and, as we shall see later, from each other. This phenomenon is called the Hubble expansion.

The next important question is: how does the recession velocity depend on the distance of the galaxy from the Milky Way? The galaxies can be classified into types such as spiral, elliptical or irregular and the total light emitted may be assumed to show regularity within each type. But their apparent brightness on Earth depends on the distance and falls off as an inverse square law. So the apparent brightness can be converted into a distance. When the recession velocity is compared to the distance a very important regularity appears. This is a most significant discovery in cosmology. It is called Hubble's law, which states that the recession velocity is proportional to the distance. The ratio of the velocity and the distance is thus a constant, i.e., the Hubble parameter. Its value is notoriously difficult to measure but now we do know it to be close to seventy, within ten percent, in certain units. These units, which are not crucial to the general discussion, are kilometers per second per megaparsec, where a megaparsec is the distance light travels in about three million years.

How does this tell us when the present expansion phase began? This requires the use of the equations of the General Theory of Relativity together with two assumptions. The first assumption is that the universe at the large scale is the same, on average, in each of the three directions of space. This is called isotropy and is supported by observations which indicate that no preferred direction exists in the universe. The second assumption is that, on average, all positions in the universe are equivalent. This means that in all galaxies (hypothetical!) observers would see the recession of other galaxies according to Hubble's law. This assumption is called homogeneity. The combination of these two assumptions, isotropy and homogeneity, is technically known as the cosmological principle.

Combining the cosmological principle with the general theory of relativity gives rise to a mathematical equation known after its inventor as the Friedmann equation which characterizes the expansion of the universe in terms of a scale factor which is a function of time and specifies the typical distance between galaxies. Inserting the known Hubble parameter and the present known composition of the universe then enables us to calculate the scale for all past times. Note, in passing, that we cannot do this for future times with confidence because we do not know with certainty how the composition of the universe will evolve in the future. For the past we have good confidence and we find a striking conclusion: run in reverse, the contracting universe is seen mathematically to shrink to a point at a well-defined past time. At that time the universe may have begun in some unimaginably powerful explosion called the Big Bang. Our present expansion seems to have a beginning and we know when. It was some 13.7 billion years ago, give or take two hundred million years. The age of the un...