![]()

INTERNATIONAL MACROECONOMICS

![]()

CHAPTER 10

Balance of Payments

Preview

This chapter introduces the adjustment mechanisms of the balance of payments BOP. Issues include how a country finances a trade deficit and what happens with the foreign currency of a trade surplus. Another issue is the effect of government deficits and surpluses on the BOP. The potential of government policy to influence the BOP is examined. Specifically, this chapter examines:

• Import and export elasticities and the trade balance

• Components of the BOP

• The government budget and the BOP

• International roles of monetary policy and fiscal policy

INTRODUCTION

Excess supply and demand adjust continuously in export and import markets. If the price of an import rises, import quantity falls and spending adjusts. The higher price increases domestic production, diminishing imports. If imports fall enough, import spending falls with the higher price.

A higher price for an export increases export revenue unless the export quantity falls by a larger percentage than price rises. For economies dependent on export revenue, international price changes can be critical. Examples are Colombia and coffee, Saudi Arabia and oil, Costa Rica and bananas, and South Africa and gold. Even for large diversified countries, international prices changes can be important. When the price of imported oil rose with the embargoes of the 1970s, large developed countries felt the shock.

With thousands of international markets, no country spends on imports exactly what it earns from exports during a year. The current account of international cash flows in the balance of payments BOP includes trade in goods and services plus net interest payments. If the current account is not zero, there is international borrowing or lending. A current account deficit is financed through international borrowing or selling assets. A current account surplus implies international lending or buying assets.

This chapter describes the fundamental mechanisms of BOP adjustment. Current and capital accounts describe the international adjustment process.

Government economic policy may influence the BOP. Fiscal policy refers to government spending and taxes. Monetary policy refers to control of the money supply. This chapter explains why fiscal and monetary policies are poor tools to influence the BOP.

A. ELASTICITIES AND THE TRADE BALANCE

Changing prices of traded goods affect export revenue and import spending. Imagine you own a warehouse full of car parts and their export demand rises. If you operate a plant producing car parts, you might increase production, hire labor, buy supplies, and invest in plant and equipment.

Changing prices of merchandise imports and exports affect the balance of trade BOT equal to export revenue minus import spending. The balance on goods and services BGS includes trade in merchandise and services,

BGS = X – M.

Changing Export Prices and the BGS

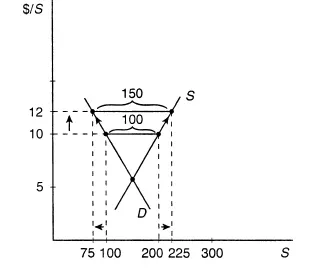

A higher price for an export increases production and export revenue but domestic consumers pay the higher price. In Figure 10.1 at a world price of $10, exports equal 100 units of business services. Production is 200 units and 100 units are consumed. Exporters can sell as much as they want at the international price.

Figure 10.1

Higher Export Prices

When the price of exported services rises from $10 to $12 the domestic quantity demanded falls to 75 and the quantity supplied rises to 225. Exports rise from 100 to 150. Producer surplus rises but consumer surplus falls.

If price rises to $12 domestic consumers cut consumption to 75 and producers increase output from 200 to 225. Excess supply or exports expand to 150 at the higher international price.

Both producers and consumers respond to the price change. There is no explanation of why the international price rises in Figure 10.1. The price could be increasing because of rising demand in the rest of the world for telecommunications, banking, and financial services.

Selling more services at the higher price increases export revenue. The level of exports rises by 50, export revenue rises from $1000 to $1800, and total revenue of domestic firms rises from $2000 to $2700. Total revenue includes export and domestic revenue. Producer surplus increases. Domestic consumers pay a higher price and consume less, and consumer surplus falls. Consumers spend $900 on 75 units, less than the previous $1000 on 100 units. The gain in producer surplus outweighs the loss in consumer surplus.

A higher export price can be caused by anything that increases global demand or decreases global supply. This principle is illustrated with an increase in the excess demand in the foreign country in Figure 10.2. Eastern Europe, for example, is opening to EU banks and financial firms. Foreign excess demand and export revenue increase. Figures 10.1 and 10.2 are consistent. The higher foreign excess demand in Figure 10.2 is the cause of the higher price in Figure 10.1. In Figure 10.2 the price increase is endogenous, explained by the model. In Figure 10.1, the price change is exogenous, outside the model.

Higher export prices raise export revenue and the BGS.

EXAMPLE 10.1 Price Taking Small Open Economies

Are small economies price takers in their export markets? Arvind Panagariya, Shekhar Shah, and Deepak Mishra (2001) find that Bangladesh faces an import elasticity of 26 in textiles and apparel products. A 1% increase in the price of these products by Bangladesh reduces the quantity of exports by 26%, very elastic indeed. These exporters in Bangladesh have no market power, making the price taking assumption reasonable. The same condition holds for a wide range of products and countries.

Changing Import Prices and the BGS

Imports are inversely related to their domestic price. If the price of an import rises, its level falls with a decrease in quantity demanded and increase in the quantity supplied. Domestic consumers substitute away from higher priced imports, and domestic firms increase output. Consumers are hurt by the higher price but producers benefit.

An example of increased import prices occurred when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was able to triple the price of oil in the 1970s. Domestic consumers had to pay higher prices while the domestic oil extraction industry boomed. Bad weather in Colombia decreases the supply of coffee and drives up the international coffee price. Dollar depreciation raises the dollar price of imported automobiles.

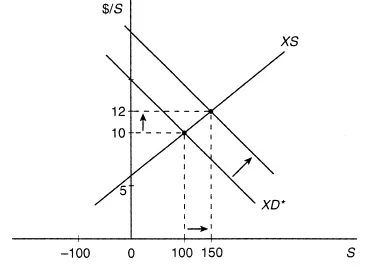

Figure 10.2

Increased Foreign Demand for Home Exports

When foreign excess demand for home exports XD* rises, the international price is pulled up from $10 to $12 and the quantity exported by the home country increases from 100 to 150.

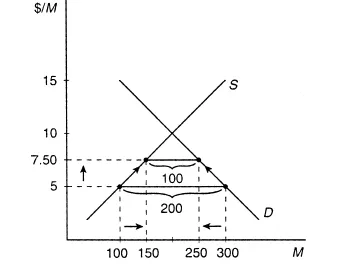

Consider the exogenous increase in the price of imported manufactures from $5 to $7.50 in Figure 10.3. The domestic quantity demanded falls from 300 to 250 as consumers switch to substitutes. The higher price also has the effect of lowering real income. Spending by domestic consumers increases from $1500 to $1875. Consumer surplus falls more than producer surplus rises. The quantity supplied domestically rises from 100 to 150 as domestic industry responds to the profit opportunity. Revenue of domestic firms rises from $500 to $1125. Producer surplus rises, taking some of the previous consumer surplus. The domestic manufacturing industry benefits from the higher price.

Higher import prices help the domestic import competing industry but hurt domestic consumers.

The change in import spending with the higher price of imports affects the BGS. Import spending falls from $1000 to $750, raising the BGS. Import spending may rise, however, depending on the import elasticity.

Import Elasticities and the BGS

If there is little opportunity for adjustment to a higher import price, import demand is inelastic. A price increase then results in increased import spending because imports do not fall enough to offset the higher price.

Figure 10.3

Higher Import Prices

An increase in the price of imports from $5 to $7.50 increases quantity supplied domestically from 100 to 150. Domestic quantity demanded falls from 300 to 250. Imports fall from 200 to 100. Import spending falls but rises if imports are inelastic. The loss in consumer surplus is greater than the gain in producer surplus.

If the price of imports and import spending are negatively related as in Figure 10.3, import demand is elastic. If consumers and firms have the time and opportunity to adjust imports, import spending can fall with a higher price.

In the 1970s at the time of the increase in oil prices, consumers were driving large inefficient cars and were not concerned with spending on fuel. There was little immediate opportunity for decreasing oil consumption with the higher prices. Oil imports were inelastic and OPEC oil export revenue rose.

In the face of consistently high oil prices, however, cars became smaller and more fuel efficient. Houses were insulated and heating and cooling technology improved dramatically. Over time, oil consumption fell. On the supply, side, domestic drilling was taking place in mountains and deeper offshore and government land was opened to drilling. The quantity of oil supplied domestically increased. England discovered oil in the North Sea and nonOPEC production increased. OPEC learned about import elasticity as their export revenue tapered and imports proved more elastic.

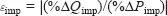

The import elasticity summarizes the relationship between import prices and spending. It is the percentage change in imports divided by the percentage price, change in absolute value:

The symbol means “change in” and “%ΔX” is “the percentage change in X “. Quantity Q imp and price Pimp are inversely related but in absolute value the import elasticity is positive.

To find percentage changes, subtract the original level from the new one and divide by the average. In Figure 10.3, the %ΔQimp is (100 – 200)/150 = -.667 = – 66.7% and %ΔPimp is ($7.50 – $5)/$6.25 = 0.4 = 40%. The import elasticity in Figure 10.3 is then |-66.7%/40% | = 1.67.

If the import elasticity is greater than one, demand for imports is elastic and price and import spending move in opposite directions. If the import elasticity is less than one, the change in the level of imports is not large enough to offset the price change. Imports are inelastic and spending increases.

The effect of a price change on import spending depends on the import elasticity. If imports are inelastic, price and import spending are positively related. If imports are elastic, price and import spending are negatively related.

Whether a higher price for imported oil, coffee, bananas, automobiles, tele-vision sets, or tires increases or decreases import spending is always an empirical issue. Countries have different import elasticities in their various import markets.

There are higher import elasticities for goods that

• have more elastic supply

• have more available substitutes

• are a larger share of con...