![]()

Chapter 1

WHAT MAKES PRODUCTS GREAT?

A design-inspired product delights the customer. The product emphasizes sophisticated simplicity and economy of means and low impact. If a product's use is apparent, simple, and clear, it will stand out from all those that compete for our attention. Great products are those that have grown in meaning and value over their—and generations of users’—lifetimes. They capture our hearts and make our lives easier, better, or more interesting. Elegant products live on long after trivial variations have been relegated to the trash heap.

Design-inspired innovation requires creativity of a higher order, whether the products are professional tools, machinery for production, consumer goods, or services. It is, in essence, a synthesis of technology and users’ experiences—boundaries that we observe blurring. Increasingly, products succeed because they have associated software and services that enhance their value. In the end, what the user remembers is a delightful experience with the entire package, and not whether that experience was provided or enabled by any particular aspect of the design.

Most innovation improves products along accepted trajectories of higher performance and lower cost. By contrast, strikingly innovative products broaden and change the boundaries of performance, usefulness, and meaning. Few designs result in products that create such dramatic market success that they drive a company's overall competitive strategy. People today hunger for products that offer more than sufficient function, high quality, and low cost. Even superb functionality no longer assures success for a new product. To achieve inspired designs and innovations, the aspiration must be for excellence and elegance. Excellence is achieved when a product is eminently good. Elegance—the tasteful richness of a product's design—is achieved when a product is neat and simple.

Customers do not necessarily want a wide variety, but they do want what is exactly the right choice for them. There is a growing richness of variety in the component supply environment, which enables greater creativity, combination, and experiment at the system level, but at the same time widens competition, doubly so when new materials and software capabilities are considered. Modularity means that we have the growing ability to design and produce products for small markets or even for a single customer. An example, a new concept for a riding saddle, is explained in detail below.

Design-inspired innovations seem to be aimed primarily at elite consumers in highly developed economies, but we believe that there is no reason to maintain such an excessively narrow focus. Design-inspired innovation creates products that have meaning. Many people strive toward a world of greater beauty, humanity, and ethics, as well as one that provides basic necessities—and we sense a rapidly growing wave of interest in creating more meaningful products that also reduce waste and reside easily in our natural and cultural environments. In the developing world, greater numbers of people aspire to have the goods and services enjoyed in developed economies, while even greater numbers aspire simply to have basic products and services. More products seem to emphasize sophisticated simplicity rather than just a welter of features, and more products seem to emphasize economy of means and low impact rather than simply economy alone.

For example, Tim Brown, head of IDEO, noted his company's success in developing a disposable injection pen for providing insulin inexpensively to help diabetics. Examples in later chapters include a simple and effective emergency shelter and less wasteful designs for food packaging. Groups such as Britain's Sorrell Foundation and MIT's AgeLab are searching for approaches to provide better experiences and products for both younger and older clients.

Our thesis is that design-inspired products, those with both excellence and elegance, will be both more profitable and enduring. Of course, there are worries. Christopher Lorenz, in his seminal 1986 work on corporate use of design, warned:

“[T]he trouble is that right does not always triumph, and principles are not always borne out in practice. Existing deterrents against the fully-fledged use of industrial design in many companies could take on new significance if globalization is managed badly. Design would then be pushed back to the dark ages of skin-deep styling, and the companies would be deprived of that ‘meaningful distinction’ which, as Theodore Levitt rightly argues, is so crucial to the creation of competitive advantage in an era of crowded markets and global competition.”1

Ironically, the best products may be the ones that disappear almost entirely: the human light, the music library, the wheelchair, a waste handling system. All of these, and other examples, are presented in detail in subsequent chapters, where we put what makes them “best” in the context of excellence and elegance.

Design, especially its integration with other functions of a firm and its strategy, has received less emphasis in previous research than is merited by its importance for success in a competitive environment. For example, as Procter & Gamble CEO A.G. Lafley, says:

“I’ve been in this business for almost thirty years, and it's always been functionally organized. So where does design go? We want to design the purchasing experience—what we call the ‘first moment of truth’; we want to design every component of the product; and we want to design the communication experience and the user experience.”2

Where, indeed, does design go? We will argue that it must constitute the beginning of the innovation process and consider the totality of a product's use and life rather than the design process being one in which the product is just conceived as an artifact or an implement.

What is design-inspired innovation?

How does it lead to competitive advantage?

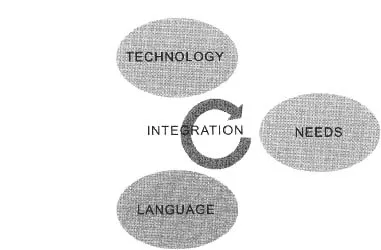

A growing number of companies recognize the importance of design-inspired innovation, especially those that aim to strengthen and maintain high product value. These companies are willing to take the large risks associated with this quite complex and uncertain approach. To answer the questions above requires taking the widely acknowledged definition of design as the integrated innovation of function and form and adapting it further to the framework illustrated in Exhibit 1.1.

The Exhibit shows graphically that three types of knowledge are essential to the innovation process—knowledge about user needs, technological opportunities, and product languages. The last component concerns the signs that can be used to deliver a message to the user and the cultural context in which the user will give meaning to those signs. The classic dialectic of function versus form leads designers to relegate the latter to the aesthetic appearance of products. Indeed, the debate often focuses simplistically on the contrast between functionalism and styling—particularly in industries such as furniture and lighting, where aesthetic content is considered to be the key driver of competition. Exhibit 1.1 expands and elaborates the concept that great design captures the meaning of products, as well as function and customer needs.

Exhibit 1.1. Design as the integration of technology, needs, and language. Adapted from Verganti, 2003.

In design-inspired innovation, the balance among technology, market and meaning is unique. None can be neglected. Rather, balance results from a vision about a possible future. In Chapter 4, we refer to this as an “ideal design.”

What really matters to the user, in addition to functionality, is a product's emotional and symbolic value—its meaning. If functionality aims at satisfying the operative needs of the customer, the product's meaning tickles one's emotional and socio-cultural needs. As Virginia Postrel argues:

“…ultimately, the only way to mitigate aesthetic conflicts is to establish design boundaries that recognize the wide variety of people and the impossibility of deducing from aesthetic principles what individuals will, or should, value. We have to return to Adam Smith: to accept the importance of specialization and to understand that a large market of many people need not be a mass market of homogeneous goods. Good design boundaries…will embrace pluralism.”3

Lorenz argues that this may seem like trying to have it both ways, but that a critical factor in design is to manage and balance just such ambiguity.

How can a firm achieve a design-inspired innovation? How can it define new meanings that are successful in the marketplace? To answer these questions, let us first look generally at innovation as the result of a process of generating and integrating knowledge.

Product and service design should not be an isolated function within a company. Rather, it should involve every single aspect of the company working together on the entire customer experience. That experience begins the moment the customer first comes into contact with the product, perhaps in a showroom or an advertisement, and continues through every aspect of the interaction across the life of the product or the length of the service. This illustrates that the product itself is only a part of the experience—in some cases, a small part. It is critical, then, that product design teams include members with diverse knowledge of finance, marketing, service, logistics, and other functions.

A Business Week article argued: “[A]s the economy shifts from the economies of scale to the economics of choice and as mass markets fragment and brand loyalty disappears, it is more important than ever for corporations to improve the ‘consumer experience.’ ”4 This shift can be seen at design firms such as IDEO, where, as CEO Tim Brown said in a presentation at MIT: “[T]he firm has moved strategically from designing products, to designing services, to currently designing entire customer experiences with products and services.”

Procter & Gamble is now IDEO's largest single customer. IDEO has moved beyond products, services, and customer experiences to an attempt to help Procter & Gamble itself design a culture to foster greater innovation. As head A.G. Lafley, who is attempting to put design “into the DNA” of Procter & Gamble, says:

“I think it is value that rules the world. There is…evidence across many categories that consumers will pay more for a better design, better performance, better quality, better value, and better experiences. Our biggest discussion item with…retailers is getting them to understand that price is part of it, but in many cases not the deciding factor.”5

Product designers, then, must become designers of the customer experience. The Apple iPod, discussed in Chapter 2, offers a prime example. The device itself is nicely designed, but its most important competitive advantage is its seamless integration with more important aspects of the customer experience, such as the iTunes website where content is easily made available to the user. Significantly, the newest service offered as part of the content provided on an iPod, the so-called “Podcast,” was neither designed nor created by Apple. Rather, it is a creation of a user community encouraged and enabled by Apple's use of standard connections in its product and open standards for its content provision. Podcasts now provide not only time-shifted news and broadcast content of all sorts, but myriad other possibilities from museum audio tours to updates about family events.

More successful designs often involve an extended ensemble of services and accessories that enhance and reinforce the users’ experiences. These may arise through open standards or user communities that encourage users and partners to develop them. Likewise, design firms that work on products that a customer can use easily and in which function is amplified through attendant accessories, systems, and services will be more successful than others.

What strategies encourage design-inspired innovation?

Success in design-inspired innovation requires a broad search for information and robust experimentation, with lots of feedback from customers on both steps. Designers who create modular designs allow greater variety and experimentation at lower cost per experiment, thus creating a greater chance of learning quickly from failure, and in turn heightening the chances of success. Likewise, design firms that introduce a greater number of prototypes may grow more rapidly than those that maintain a tight focus. Modular design is a pre-condition for so-called mass customization. With readily connected modules, customers can more easily select the modules that provide an ensemble of preferred features. According to Joe Pine, the most ingenious companies provide design software and services (or “design tools”) that readily allow customers to visualize the result of a selected combination.6 This idea is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

Seeking and Experimenting

Clearly, design-inspired innovation might involve much more seeking and experimenting than planning. Great designs might be those that provide for more variations to meet particular customer needs or specifications, or for more variations to be tried quickly in the marketplace to zero in on the version most highly suited to customer needs and preferences. “The work of Scherer (1999) shows that returns from innovation are highly skewed. Only a few innovations in a portfolio produce significantly above-average returns. Similarly, only a small number of academic publications get very highly cited, a small number of patents produce most income, and a small number of products yield the majority of sales. Although the performance of incremental innovations tends to be less skewed than radical innovations, the implications of these ske...