![]()

5

OF ABCs AND 123s

How Singapore Children Studied and Learned

Alvin used to dread waking up in the morning. The start of a new day meant he had to go to school – a fearful place, without his mother and full of strangers. His two years in kindergarten did little to assuage his fears. For the first six months of primary one, Alvin would cry and cling on to his mother every day, starting from the moment he had to get ready for school. For his mother, a new school day meant having to undergo the stressful process of cajoling, scolding, threatening or just hardening her heart in order to get her son to go to school. Given Alvin’s unusually persistent fears, his principal made an exception by allowing his mother to stay in the school canteen while he was in class, the only parent granted this privilege. Even then, Alvin would make excuses to go to the toilet at every opportunity, just to make sure his mother was still in the canteen.

In contrast, Alvin’s elder sister enjoyed school. After her first day of school, her grandfather came home and declared to the family that they did not have to worry about the girl. He had gone to spy on her just to be sure she was alright and saw that his fears were unfounded. She was the first one to go out of the classroom, making a beeline for the canteen, when the recess bell rang. By the time her

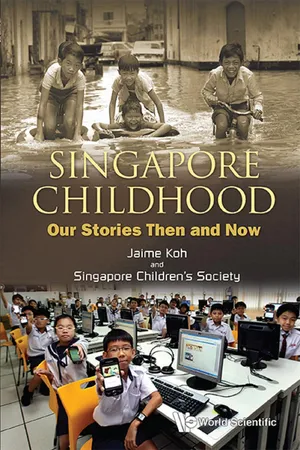

First day of school

Eager parents whip out their compact cameras and mobile phones to capture their child’s first day in a new school.

Separation anxiety

Parents or children, who are the more anxious? Parents in the school canteen ensuring that their children do not go hungry on their first day at Teck Ghee Primary School, 1983.

classmates made their tentative way there, she was already halfway through her noodles. By the end of recess time, she had figured out where the toilets, hall and staff room were.

If Alvin was the reluctant school boy, his sister was the eager beaver who would hurry her mother along for fear that she would be late for school, even when she was way too early. She looked forward to school every day, wondering what the teachers would teach and whether she and her friends would be fast enough to chope their favourite spot under the ancient flame-of-the-forest tree in the field during recess for a game of hopscotch.

Getting a Headstart

So, school can be a time of fun or fear, depending on one’s personal experience. Either way, almost every Singapore child is familiar with the school experience; it is an essential part of their lives. But it was a different story just a few decades ago. Then, not everyone had the opportunity to study. Unlike today, primary education was not universal, let alone compulsory. Today, the literacy rate in Singapore is close to 100 per cent.a In 1957, only slightly more than half the population was literate.b

Education has become an important yardstick of economic and social success in Singapore. So much so that in recent years, kiasu1 parents wanting to gain every advantage for their children often resort to extreme measures. There are now parents putting their toddlers on waiting lists for popular kindergartens or enrolling

them even before they are born! The high cost and long wait-lists at some private preschools prove no deterrent to some parents who are willing to fork out high monthly fees and wait as long as they can get their children into a preschool of their choice. The situation for ‘brand name’ primary schools is even more extreme. Some parents move house so that their address is in the vicinity of the chosen school; while others volunteer their time in the school, hoping to take advantage of the privilege accorded to families residing near a school, of securing a place for their children when the enrolment exercise starts.

This is a far cry from the days when Mrs Pek Swee Hee began her career as a kindergarten teacher in 1967. At that time, only a handful of children attended preschool and parents were not particular about the schools their children attended. Mrs Pek taught at a preschool in the Rochor area. The lessons were simple and focussed on teaching the children how to write the letters of the alphabet, how to count and how to read.

Even in those days, putting children in kindergarten was as much about childcare as it was about the child’s education. Mrs Pek sometimes visited the children at home when they missed school or appeared unhappy. These visits often revealed the poverty and the hardships that many families struggled with and the impact they had on children. Mrs Pek remembered one occasion when she visited a child at home after he missed school for several days. It was during the visit that she found the child’s father to be sick and the family unsure of what to do given their poor financial situation. Mrs Pek advised them to seek medical care at a nearby outpatient clinic where the services were heavily subsidised. That problem solved, the child came back to school. It may seem like a simple problem, but it was one that weighed on the family and affected the child.

The Politics of Education

“So you’re the bad guys!” was Annie’s* quip when she learnt that her husband and sister-in-law, Xiao Mei*, attended a kindergarten run by the Barisan Sosialis (Socialist Front). This was a political party formed in 1961 by breakaway members of the People’s Action Party (PAP). Under the shadow of the political ideological conflict of the 1950s and 1960s, “the Barisan” was commonly perceived to have communist links and to be on the wrong side of the political field, hence the “bad guys”. Annie recalled often hearing the adults talk about the Barisan people as the bad guys. By extension, those who sent their children to Barisan kindergartens were pro-communists. That impression, however skewed, stayed with Annie.

* Not her real name.

Education was not above politics. What was taught, how it was taught and how the school system was run did not escape the influence of politics. Take the case of kindergarten education. During the 1960s, both the Barisan and the PAP operated kindergartens as part of their political outreach programme. The kindergartens were situated in convenient locations within housing estates and villages where they were easily accessible, and the fees were kept low so that most families could send their children to be schooled. That was where their similarities ended. Since they were established by rival political parties, the nature of the education these kindergartens offered were inevitably different.

The Barisan kindergartens had a stronger Chinese orientation. Xiao Mei and her three older siblings attended a Barisan-run kindergarten at Nee Soon (now Yishun) in the late 1960s. “My family was very Chinese-oriented and chose for us to attend the Barisan Sosialis kindergarten because it had a strong Chinese foundation,” she said, adding that the teachers were very traditional and very strict. “We were all expected to sit still and could not fool around. We had to greet our teachers and obey them to the letter,” she said. “I was always scolded by my teacher because I could not fit the complicated Chinese characters of my name

into the small squares in our exercise books. There were so many strokes in one character – we were still using the traditional script then – and the squares were so small! I got caned for letting my strokes ’spill out’ of the squares.”

Although Xiao Mei remembered learning the alphabet in the kindergarten, what stuck in her memory were the Chinese songs of the Cultural Revolution in China.

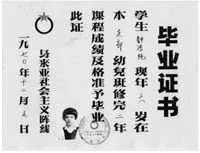

The Barisan chop

A kindergarten graduation certificate dated 1970. No wonder the child looks solemn – a tiny figure surrounded hy huge imposing characters. Then as now, documentation is the thing in literate cultures.

The little children were singing songs with lyrics such as, “Dear Chairman Mao, the sun in my heart”, without knowing what they meant. “We even had accompanying hand gestures similar to what the students and Little Red Guards2 in China would do when they perform!”

Annie, who attended a PAP-run kindergarten in Yio Chu Kang in the early 1960s, had a different experience. “I remember we had a red and white checkered uniform. We learned the alphabet and basic counting,” she said. Although Annie and her schoolmates also learned to read and write Chinese, the classes did not have the communist overtones of the Barisan kindergartens.

In colonial Singapore, there was no unified system of education. Although the government set up a few English schools, education was largely provided by the ethnic and religious communities. Churches funded English-language mission schools. Local mosques ran Malay and Arabic classes. Chinese philanthropists, clans and villages established schools in both the city and rural areas. Plantation owners started small-scale schools for children of the mostly Tamil plantation workers. The lessons were in the teachers’ native tongue – English, Malay, Tamil, and the various Chinese dialects. In the case of the Chinese schools, Mandarin was not much used before the 1930s. The colonial authorities had encouraged the continuation of dialect-based Chinese education over Mandarin as the latter was considered to have “too much political significance”, linking the schools and their pupils to China instead of colonial Singapore. Each school hired their own teachers, selected their own teaching materials and implemented their own grading systemsc

Among this plethora of schools, the greatest divide was between the English- and Chinese-stream schools. The English schools, including mission schools and schools funded by the colonial government, used English as the medium of instruction for all subjects and adopted the Western model of education. Attending these schools conferred a certain degree of advantage to the students; they were seen to be given a leg-up in life because they were educated in the Western system that would provide them the language skills to interact with the Europeans in the world of commerce later. This advantage was increased for the Peranakan Chinese who spoke English and Malay rather than Chinese anyway.

After Mandarin was finally designated the national language of China in 1932,d the Chinese schools in Singapore increasingly used Mandarin as the medium of instruction and they also increasingly mirrored the educational system and curriculum in China. Most of tne teachers were recruited from China and the textbooks used were also imported from China. In the first half of the 20th century, Chinese education was highly politicised, influenced strongly by events in China, such as the 1911 Nationalist revolution, the Japanese occupation of China from 1937 and the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

There was a general perception that the Chinese school students were more loyal to China than they were to Singapore. This view was fuelled by the overtly pro-China gestures these schools adopted, such as the singing of the national anthems of China – first,

The Three Principlesof the Nationalist Government and later,

March of the Volunteers ,

the revolutionary anthem of the Communist Party that subsequently became the present national anthem. It did not help that a small but vocal group of radical students and agitators saw the Chinese schools as a channel for their anti-colonial stance.

Yet, for most parents, the distinction between the two streams of education had a more practical implication – job prospects. One could easily find a clerical job in one of the many Chinese enterprises if one was literate. With a bit more education, a managerial post was attainable. But the well-paying jobs were in the European mercantile firms and the civil service, and these ...