![]() HEPATITIS B VIRUS

HEPATITIS B VIRUS![]()

Chapter 1

Natural Course of Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection

Chia-Ming Chu and Yun-Fan Liaw*

Introduction

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a global public health problem. Despite the development of highly effective vaccines against the disease since the early 1980s and the implementation of universal newborn vaccination programs in more than 168 countries, there is still a huge burden of liver disease due to chronic hepatitis B. An estimated 350 million people in the world are chronically infected with HBV and 75% of them reside in Asia-Pacific region.1 Although most hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) carriers will not develop hepatic complication from chronic hepatitis B, between one-quarter and one-third are expected to develop progressive liver disease, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and 15–25% will die from hepatitis B-related liver disease. It is estimated that worldwide over 200,000 and 300,000 HBsAg carriers die each year from cirrhosis and HCC, respectively.2 In Taiwan, HBsAg carriers are at 5.4- and 25.4-fold, respectively, increased risk of mortality from cirrhosis and HCC.3

The natural course of chronic HBV infection is complex and variable and has still not been completely defined. Substantial improvement in the understanding of HBV virology and host immune response to HBV, combined with the recent availability of highly sensitive HBV DNA assays and quantitative HBsAg assays, during the past decades, has led to new insights into the natural history of HBV infection. A better understanding of the clinical outcomes and factors affecting disease progression is important in the management of patients with chronic HBV infection.

Epidemiology of Chronic HBV Infection

Worldwide, an estimated two billion people have been infected with HBV, and some patients with acute HBV infection develop chronic HBV infection, defined as persistence of serum HBsAg for more than six months. The risk of chronic infection after primary HBV infection varies and depends on the age and immune status at the time of infection. Among infants born to hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive mothers, and hence infected in the perinatal period, the probability of chronic infection approaches 90%. When infected at one to five years of age, 20–30% of children become chronically infected, while among older children the probability falls to 5–10%. The risk of chronicity among normal, healthy, immunocompetent adults may be as low as 1%.1 The extremely high chronicity after perinatally acquired infection is presumably related to the immature immune system of the neonates. Another possible mechanism is that the fetus is tolerated in utero to HBV following transplacental passage of viral proteins.4

The global prevalence of chronic HBV infection varies greatly among different geographical areas, and can be classified into high-prevalence (Southeast Asia, China, Sub-Saharan Africa and Alaska); intermediate-prevalence (Mediterranean countries, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Japan, Latin, and South America); and low- prevalence areas (USA, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand) based on the prevalence of HBsAg carriers of >8%, 2–8%, and < 2%, respectively.1 Associated with a wide range in prevalence of chronic HBV infection are differences in the predominant mode of transmission and age at infection. In high-prevalence areas, perinatal transmission is common and accounts for 40–50% of chronic infection in Southeast Asia. In contrast, inapparent parenteral spread from child to child is the major mode of transmission in Sub-Saharan areas. This difference is related to the higher prevalence of HBeAg in Asian carrier mothers (40%) than in African carrier mothers (15%),5,6 as 80–90% of HBeAg-positive mothers will transmit the disease to their offspring, as compared with 15–20% of those seronegative for HBeAg.7 In low-prevalence areas, hepatitis B is a disease of young adults, typically those who have high-risk behavior such as sexual promiscuity or drug abuse or are in high-risk occupations.

The worldwide incidence of HBV infection is decreasing as a result of vaccination and public health education on preventive measures against risk factors. After the implementation of universal vacci-nation programs in newborns, the HBsAg carrier rate among children in Taiwan decreased from 10% in 1984 to <1% in 2004.8 The estimated total population of HBsAg carriers in Taiwan decreased from 2.9 to 2.6 millions.9 In the United States, the incidence of reported acute hepatitis B declined by 81% from 8.5 to 1.6 cases/100,000 during the period 1990 to 2006. However, immigrants from high-prevalence areas are now responsible for an increasing burden of chronic HBV infection in many developed countries.

Clinical Presentation

Only a small percentage of patients with chronic HBV infection reported a history of acute or symptomatic hepatitis. In low- or intermediate-prevalence areas where HBV infection is predominantly acquired during adult or childhood years, approximately 30–50% of patients with chronic HBV infection have a history of acute hepatitis. In patients from high-prevalence areas, where HBV infection is predominantly acquired perinatally, clinically evident hepatitis is almost lacking. Most patients are incidentally identified to be HBsAg carriers during health check-up or routine screening, and a few due to non-specific constitutional symptoms. In high-prevalence areas such as Taiwan, as high as 40% of HBsAg positive patients with overt acute hepatitis are actually chronic HBsAg carriers who remained unrecognized until they present the episode of acute hepatitis. They were HBsAg seropositive but seronegative for immunoglobulin class M antibody against hepatitis B core antigen (IgM anti-HBc), so-called “previously unrecognized HBsAg carriers with acute hepatitis flares or superimposed other forms of acute hepatitis.”10 In these areas, a history of acute hepatitis in HBsAg carriers is more likely an acute hepatitis flare of chronic HBV infection rather than acute hepatitis B.

The patients with chronic HBV infection may present one of the following four biochemical and serological profiles: (1) HBeAg positive with normal serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels; (2) HBeAg positive with abnormal ALT levels; (3) HBeAg negative, antibody to HBeAg (anti-HBe) positive with normal ALT levels; and (4) HBeAg negative, anti-HBe positive with abnormal ALT levels. These four patterns of presentation actually represent different phases of chronic HBV infection.

Phases of Chronic HBV Infection

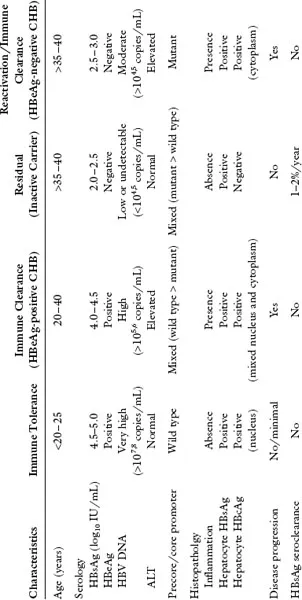

As a result of the dynamic interplay of complex interactions involving HBV, the hepatocyte and the host immune response, the natural course of chronic HBV infection consists of distinct phases, characterized and diagnosed on the basis of HBeAg/anti-HBe serology, serum HBV DNA levels, ALT levels and liver histology. Typically, chronic infection acquired perinatally or during infancy has three phases: the immune tolerant, immune clearance, and inactive residual phases.11–13 In a subset of inactive carriers, HBV may reactivate and trigger immune mediated liver injuries. This reactive phase can be viewed as a variant of immune clearance phase..1,14 In adult-acquired chronic infection, there is usually no or very short initial immune tolerant phase. Otherwise, the clinical course is essentially the same as seen in patients with perinatally acquired infection. The clinical, serological, histopathological and virological characteristics of these dynamic phases of chronic HBV infection are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Phases of Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Clinical, Immunohistopathological and Virological Characteristics

ALT — alanine aminotransferase; CHB — chronic hepatitis B; DNA — deoxyribonucleic acid; HBcAg — hepatitis B core antigen; HBeAg — hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg — hepatitis B surface antigen.

Immune Tolerant Phase

The initial phase of chronic HBV infection is characterized by the presence of HBeAg and very high serum levels of HBV DNA (usually > 2 × 107IU/mL or > 108 copies/mL); normal ALT levels; and normal or minimal histological changes11–13 with intrahepatic hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) expression diffusely and predominantly in the nucleus.15 There is usually little or no disease progression as long as serum ALT levels remain normal and the immune tolerance is maintained.16

The absence of liver disease, despite high level of HBV replication during this phase, is believed to be a consequence of immune tolerance to HBV. Even though HBV does not cross the placenta, the HBeAg secreted by the virus does. Experiments in mice suggest that a transplacental transfer of maternal HBeAg may induce a specific unresponsiveness of helper T cells to HBeAg in neonates. Because HBeAg and HBcAg are highly cross-reactive at the T-cell level, deletion of the helper T-cell response to HBeAg results in an ineffective cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response to HBcAg, the major target of the immune response.4 Once a chronic infection has been established, persistence of high viral load and continued secretion of HBeAg (the tolerogen) are necessary to maintain the tolerant state. The viral population identified during the immune tolerant phase usually consists of exclusively wild type HBeAg-positive (e+) HBV with little or no mutant type HBeAg-negative (e-) HBV..4,17

Immune Clearance Phase

The transition from the immune tolerance to immune clearance phase usually...