Micro-analysis Of Regional Economy In China, The: A Perspective Of Firm Relocation

A Perspective of Firm Relocation

- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Micro-analysis Of Regional Economy In China, The: A Perspective Of Firm Relocation

A Perspective of Firm Relocation

About this book

The book presents the comprehensive research findings on the basic features, formation mechanisms and evolution laws of Chinese enterprise migration, from the micro-perspective of enterprise migration; and on this basis, the influences from enterprise migration on industrial agglomeration and diffusion as well as the evolution of regional economy. The migration trends, power mechanisms, determining factors, structural and spatial effects of Chinese manufacturing industry have also been studied.

The author also puts forward policy advice on the themes above, such as the central government should pay more attention to the fairness goals in the market economy framework; some policies should be improved to positively and reasonably guide and regulate firm relocation in China, for example, enterprises from Chinese coastal areas should be encouraged to move to the mid and west areas; the industrialization and urbanization in mid and west areas should be accelerated; the economic development should be geared to the bearing capacity of natural resources and environment; industries and economic activities should be promoted to agglomerate effectively in metropolitan regions.

This book provides a comprehensive analysis on the relocation of enterprises in China, as well as the situation of China's regional economic development. The author, Wei Houkai, as an authoritative economist on regional development of China, completed his detailed survey on China's regional economy from this perspective of enterprise relocation, together with his research group. This book, doubtlessly, provides a valuable opportunity for readers in English world to obtain the realistic and rational messages about what is happening in China in certain domains. The author, whose policy advice has always been adopted by the government of China, raises some significant viewpoints based on his distinctive insight, which may be influencing the regional development route in China.

Contents:

- Regional Economic Development in China: Agglomeration and Relocation (Wei Houkai)

- Theoretical Issues in the Current Regional Economic Development (Wei Houkai)

- A Critical Review of Theoretical Research on Firm Relocation (Bai Mei)

- Characteristics and Tendency of Enterprise Relocation in China (Wei Houkai and Bai Mei)

- Dynamics and Determinants of Manufacturing Location in China (Wang Yeqiang and Wei Houkai)

- Manufacturing Location Change in China: Structural Effects and Spatial Effects:A Test of the “Krugman Hypothesis” (Wang Yeqiang and Wei Houkai)

- Manufacturing Firm Relocation in East China: Tendency and Mechanism (Jiang Yuanyuan)

- Changes in the Location of Taiwan-Invested IT Enterprises in Mainland China and Their Relocation Decisions (Wei Houkai and Li Jing)

- Corporate Headquarters Relocation of Listed Companies and Wealth Transfer in China (Wei Houkai and Bai Mei)

- Relocation Mechanism and Spatial Agglomeration of Enterprise R&D Activities (Liu Changquan)

- New Industrial Division and Conflict Management in Metropolitan Area — Based on the Perspective of Industrial Chain Division (Wei Houkai)

- Analysis of Urban Industrial Relocation's Incentive, Approaches and Effects — Taking Beijing as an Example (Fu Xiaoxia, Wei Houkai and Wu Lixue)

Readership: Graduate students, researchers and professionals interested in enterprise migration in China, in particular the influences of enterprise migration on industrial agglomeration and diffusion.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

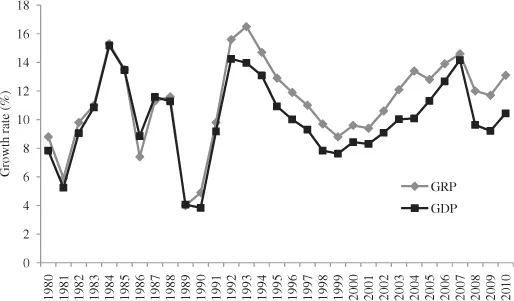

Agglomeration and Relocation

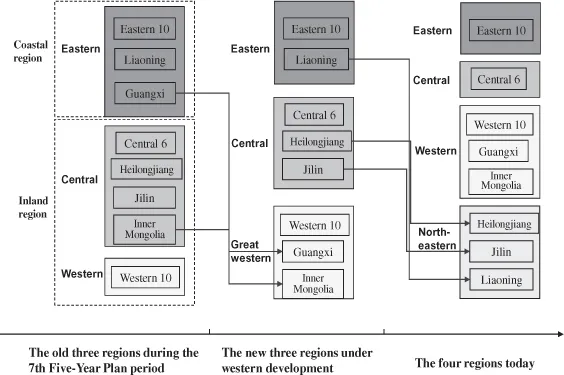

State plan | Period | Regional division |

Sixth Five-Year Plan | 1981–1985 | Coastal region and inland region |

Seventh Five-Year Plan | 1986–1990 | Eastern coastal region, central region, and western region |

Eighth Five-Year Plan | 1991–1995 | Coastal region and inland region |

Ninth Five-Year Plan | 1996–2000 | (1) TheYRD and the areas along the river, Bohai Sea Rim (BSR) region, southeast coastal region, southwest region, and some provinces and autonomous regions in south China, northeastern region, five provinces and autonomous regions in central region, and northwest region; (2) eastern region and central and western region. |

Tenth Five-Year Plan | 2001–2005 | Eastern region, central region, and western region |

Eleventh Five-Year Plan | 2006–2010 | (1)Western region, northeastern region, central region, and eastern region; (2) four categories of main functional areas including optimized, key, restricted, and prohibited development areas. |

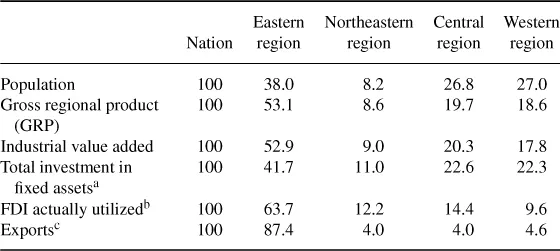

b Data in 2009.

c Computed by the origin of commodity supplies.

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Series Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- Chapter 1. Regional Economic Development in China: Agglomeration and Relocation

- Chapter 2. Theoretical Issues in the Current Regional Economic Development

- Chapter 3. A Critical Review of Theoretical Research on Firm Relocation

- Chapter 4. Characteristics and Tendency of Enterprise Relocation in China

- Chapter 5. Dynamics and Determinants of Manufacturing Location in China

- Chapter 6. Manufacturing Location Change in China: Structural Effects and Spatial Effects: A Test of the“Krugman Hypothesis”

- Chapter 7. Manufacturing Firm Relocation in East China: Tendency and Mechanism

- Chapter 8. Changes in the Location of Taiwan-Invested IT Enterprises in Mainland China and Their Relocation Decisions

- Chapter 9. Corporate Headquarters Relocation of Listed Companies and Wealth Transfer in China

- Chapter 10. Relocation Mechanism and Spatial Agglomeration of Enterprise R&D Activities

- Chapter 11. New Industrial Division and Conflict Management in Metropolitan Area — Based on the Perspective of Industrial Chain Division 309

- Chapter 12. Analysis of Urban Industrial Relocation’s Incentive, Approaches and Effects — Taking Beijing as an Example

- Index