![]()

Chapter

1

Political Legitimacy in Malaysia: Regime Performance in the Asian Context*

Bruce Gilley

INTRODUCTION

In 2004, Malaysia’s ruling National Front coalition was returned to office in general elections with 64% of the popular vote. After suffering an electoral setback in elections in 1999, the coalition returned to consolidate its rule. The ongoing support for the National Front has presented something of a puzzle for scholars because under the reign of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad from 1981 until 2003 political liberties in Malaysia steadily deteriorated. The country’s economic performance, while adequate, was weaker than that of the other Asian tiger economies where authoritarian regimes lost support.

The Malaysian case raises two obvious questions: Is political legitimacy as high as it appears? If so, what explains that result? To answer these questions, we need to consider legitimacy in some general framework that allows comparisons with other countries as well as a tracing of the legitimation process in Malaysia itself. This paper proceeds in three parts. In the first, I outline a theory of the political legitimacy of states, its analytic components and their relative importance. Using this, I proceed to an analysis of some quantitative indicators of political legitimacy in 10 Asian states, including Malaysia. This gives us some insight into the first question. In the second part, I consider the causes of legitimacy, or at least those universal causes which may explain most of the variations in legitimacy levels across states. I introduce a four–part theory of these causes, and provide an aggregation of performance for the 10 states that seems to fit observed legitimacy levels. In the third part, I consider the question of the legitimation process, namely the mechanism through which the hypothesized causal variables lead to the observed legitimacy outcomes. After introducing a general theory of this process, I consider the case of Malaysia in greater detail.

My conclusions are twofold. One is that legitimacy in Malaysia is not as high as electoral returns suggest, reflecting the importance of the analytical and empirical distinctions between legitimacy (support due to views of the rightfulness of the state) and compliance (support due to personal payoffs or coercion). Second, modest legitimacy levels in Malaysia do reflect reasonable performance of the Malaysian state on distributive and regulatory fronts that have generated legitimacy in spite of the decline of civic and political freedoms in the country.

As such, the Malaysian case is a reminder of the complexity of political legitimacy, both its make-up and its causes. This conclusion meshes with the findings in other chapters in this book, namely that not only is legitimacy a multi–faceted concept that admits of degrees, but its causes, even if confined only to political variables, may range across various types of political performance. The immediate implication is that as Malaysian society continues to modernize, the regime will need to pursue legitimacy–enhancing improvements in its performance or else introduce new, sterner forms of compliance. As the latter option was increasingly exhausted in the post–Mahathir era, it portends a period of significant governance reforms.

LEGITIMACY THEORY

The concept of legitimacy is central to much of the social sciences since it describes how power may be constituted and used in a community in ways that members accept. Within political science, its importance has been demonstrated by the Third Wave of democratizations from the late 1970s to the late 1990s which cut the proportion of the world’s states living under authoritarian rule from two–thirds to one–third. States that lack some minimal degree of legitimacy, no matter how powerful their coercive apparatus or how appealing their economic performance, have been unable to withstand citizen desires to be willing subjects of the political order in which they live.

Political legitimacy remains a complex, multi–faceted concept whose measurement is difficult and whose sources and implications may vary widely across states. Still, the increased evidence of a “globalization of politics” means that cross–national measurement and comparison of this concept is increasingly possible and fruitful. Efforts to distill a common meaning and measure of legitimacy across otherwise diverse states, of which this book is one part, are made possible by a growing universality of political experience.1

Political legitimacy can be defined as the degree to which a state is viewed and treated by citizens as rightfully holding and exercising political power. Where it is legitimate, citizens defer to political power not because of fear or favor but because of “an acceptance, even approbation, of the state’s rules of the game, its social control, as true and right.”2 In other words, legitimacy concerns evaluations of the goodness and justness of political power. It is an endorsement of the state by citizens at a moral or normative level, that is, in the light of considered views of what is best from a public perspective. This is in contrast to their compliance with the state due to non– normative coercion (police repression, restrictive laws) or individual economic or social payoffs.

Legitimacy is thus normative by nature. What is sometimes called “performance legitimacy” only makes sense to the extent that it implies the ways in which citizens evaluate state performance from a public perspective. A citizen who supports the regime “because it is doing well in creating jobs” is expressing views of legitimacy. A citizen who supports the regime “because I have a job” is not. While in practice, citizens may conflate individual payoffs with public rightfulness, the justification remains distinct, and thus liable to critique if not sustained by evidence of the public good. Much empirical evidence suggests that on both economic and political issues, people’s evaluations of performance are often from a public perspective, meaning that there is a distinct form of political support called legitimacy.3

It is possible to evaluate the legitimacy of many objects — constitutions, politicians, judges, laws, processes, and much else. If the main concern is political development, then the relevant object is the state, a political community enjoying a monopoly of power within a defined territory.4 Political development is changes in the “basic structure” of a political community. This basic structure includes the institutions, norms, and processes of that community at both central and local levels, and “how they fit together into one unified system of social cooperation”.5

More specifically, the state can be divided into two parts: state institutions and state–embedded polity. State institutions include the organizations, agencies, departments, customs, norms, laws, and processes of a political community. For most democracies, this is the only part of the state as a referent object of legitimacy. For this reason, surveys of state legitimacy typically ask questions about how people feel about the democracy in their country, or their confidence in civil servants, judges, or policemen. State–embedded polity covers those cases where leaders, parties, or governments are empirically or perceptively indistinguishable from the state. Generally speaking, citizens in democratic countries make a clear separation between their views of the state and their views of politicians, parties, and governments since these things are empirically separate.6 Nevertheless, in some states, elements in the polity have “captured” the state. In a country where people talk about “the regime” as opposed to “the government”, it is likely that there is a significant degree of state–embedded polity.7 A collapse in the legitimacy of a leader in an authoritarian regime has grave implications for the legitimacy of the state.8

In what ways can the state be seen as legitimate? I follow Beetham9 and others10 in defining legitimacy as having three principle components: views of legality, views of justification, and acts of consent. Views of legality means that citizens believe that those in power have acquired and exercised that power in a way that accords with established and accepted rules or norms. This is the classical component of legitimacy — indeed the English word itself comes from the Latin word meaning “to make legal”. In the words of Poggi, legality represents “the taming of power through the depersonalization of its exercise”.11 Views of justification means that citizens believe there are good reasons to accept the inequalities in wealth and power created by the coercive power of the state. Those reasons lie in shared beliefs about the nature and pursuit of the common good. Acts of consent are those positive actions which express society’s willingness to be obligated or compelled to perform certain duties as members of the state.

These three components intermingle in the legitimation of most aspects of the state. The legitimacy of the tax system, for example, relies not only on the provision of detailed and transparent tax laws, but also on political justification and quasi–voluntary tax–payer compliance. As a general rule, we would expect the three components to be positively correlated. If we wish to arrive at an overall evaluation of the legitimacy of the tax system, which component — evidence of citizen views of legality, views of justification, or consent — is most important? If one or two matters more, a simple aggregation of “everything” will give biased estimates. In this paper, I will simply aggregate components into a simple mean. However, a more complex measure of legitimacy would need to provide a theoretically–motivated aggregation strategy.12

LEGITIMACY MEASUREMENT

Evidence of the three components of legitimacy can be found from both attitudinal and behavioral data. In this study, I have selected the following data sources (see Appendix A for details of these indicators). For views of legality, I use a composite score based on three survey questions, two from the World Values Survey on confidence in the police and civil service and another from Transparency International on corruption in state institutions. For views of justification, I use the average score for 1996 to 2000 of “normalized civil violence”, the percentage of civil actions that involve violence, from the World Handbook of Political and Social Indicators IV. For acts of consent I use two separate measures: electoral turnout in national legislative elections in the late 1990s; and the percentage of central government revenues raised from “quasi-voluntary” or self–paid taxes, mainly income and corporate profit taxes.

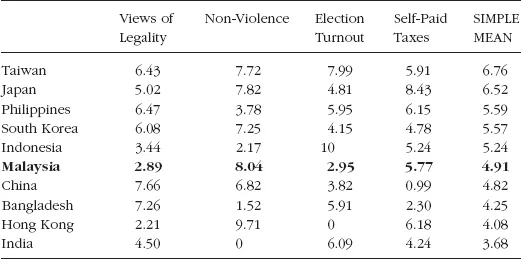

I choose 10 Asian states for which sufficient data is available and transform the data using a normal distribution into a 0 to 10 scale for all indicators (meaning a score of 5 represents the mean for all countries). The results are as follows:

Table 1.1 Legitimacy Component Scores: Scaled 0 (Worst) to 10 (Best)

Taken at face value, we can make some general observations. One is that as a matter of ranking, for the period of the late 1990s to the early 2000s covered here, the state in Malaysia enjoyed middling legitimacy levels in comparative context. Indeed, it was closer to the middle score of 5 than any other state in the 10 surveyed here. The interest of this finding may be what it says about the first question posed at the outset, namely how high is legitimacy in Malaysia. It implies that legitimacy, while modest, is not as high as electoral landslides for the ruling National Front suggest.

Second, the make-up of legitimacy in Malaysia, as with most states, varies across components. The relatively low political violence and relatively high self-paid taxes are indicative of a reasonably robust support for what might be called the “invisible state”.13 The country’s poor performance on views of legality and on electoral turnout reflects less legitimacy for the visible and everyday institutions of the state. We will later examine qualitative evidence for this legitimacy scoring in the Malaysian case. But prior to that, it is useful to remain at the macro–comparative level of analysis and consider explanations for this variation in legitimacy levels.

Explanations of Legitimacy

Legitimacy is often studied as a causal variable. That is, social scientists are interested in how legitimacy affects the way that states behave towards citizens and towards other states. The questions I want to consider here are the causes of legitimacy itself.

The question of the sources of legitimacy is as old as political science itself. Jean Jacques Rousseau set out in The Social Contract [1762] “to enquire whether there can be a legitimate and reliable rule of administration in the civil order”. Yet political science has bee...