![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Economic Structure and External Orientation

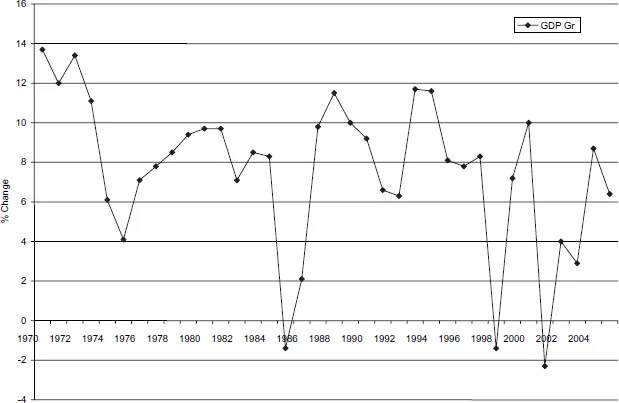

The rapid evolution of Singapore from a modest trading post under colonial rule into a modern, prosperous, self-confident and sovereign nation is one of the more notable success growth and development stories of the second half of the 20th century. The Singapore economy has experienced one of the highest rates of growth in the world over the past three decades, its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rising at an annual average rate of about 7.6% during the period 1970–2005. The growth has in turn propelled Singapore’s average real per capita income from US$ 512 in 1965 to its current level of over US$ 26,982 by 2005, which is one of the highest in the world, surpassing many developed countries (Figure 1).

However, long-term averages hide the fact that the Singapore economy has been fairly fragile over the last five years. Specifically, following the sharp downturn in the global electronics industry and the sluggish regional and global growth, Singapore experienced an acute economic contraction in 2001; the recession was the worst in thirty years. Its impact on rising rates of redundancies, bankruptcies, financial and asset markets, consumer and business sentiment, and the like, have been deep and wide-spread. The depth of the recession was largely due to the confluence of a number of negative factors, including the unfortunate and horrendous events of September 11, 2001, Bird flu and SARS, Tsunami, Middle-East war, oil-shocks and dot.com bubble crash, and it emphasized once again the acute susceptibility of the city state to external shocks. Indeed, the Singapore economy has appeared relatively fragile and much more at risk to boom-bust cycles post Asian crisis.1 It is only in the last few years that the economy has regained its robustness. The Singapore economy expanded at a strong pace of 8.7% and 6.4% in 2004 and 2005, respectively, with the growth momentum being sustained in 2006–2007.

Source: Singapore Department of Statistics.

Fig. 1. GDP Growth for Singapore Economy: 1970–2005 (2000 Market Prices).

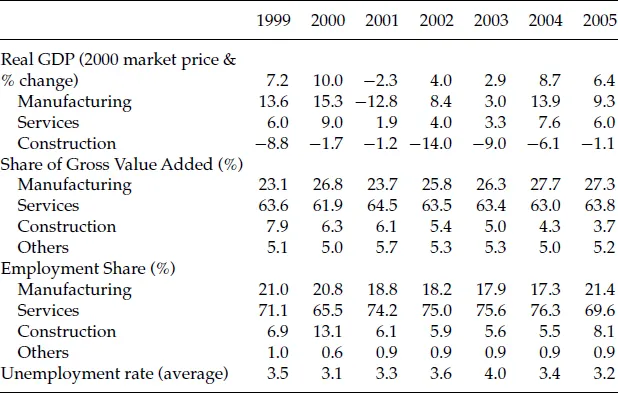

Table 1. Key Macroeconomic Indicators, 1999–2005

Services sector includes: Wholesale and retail trade, hotels and restaurants, transport and communication, financial services, business services, other services.

Source: Thangavelu and Toh (2005).

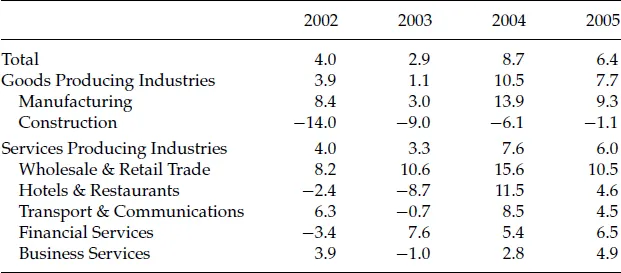

1.1.Sectoral Growth

At a sectoral level, while the construction sector has remained a drag on the economy, the economic rebound in recent years has largely been due to both non-construction manufacturing and services sectors. The manufacturing sector grew at an average pace of 8.5% between 2002 and 2005, while the services output growth averaged 5%. Within services, the wholesale & retail trade has been growing and double digits. The hotels and restaurants, financial services and transport and communications have also all rebounded in the last few years, hence driving services sector growth (Table 2). The service sector has consistently accounted for over 60% of Singapore’s gross value-added, while the manufacturing sector has accounted for about 25%. There is a conscious policy by the government to ensure that both the manufacturing and services continue to form the “twin engines” of growth for the economy.

Table 2. Key Economic Indicators by Sectors (2000 Market Prices—Change in %)

Source: Singapore Department of Statistics.

1.2.Employment and Income Distribution

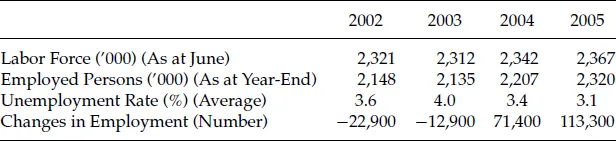

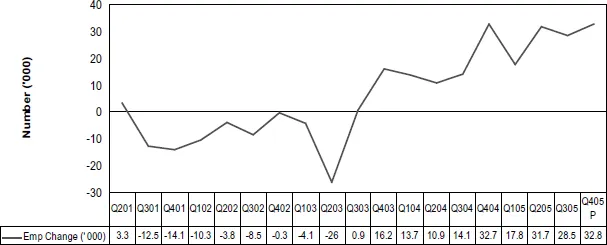

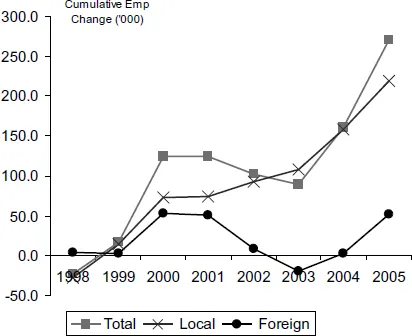

As would be expected, employment growth has lagged economic recovery and unemployment peaked at 4% in 2003. However, the strong output growth since then has been complemented by robust employment growth in 2004 and 2005 (Table 3). The overall unemployment rate has consequently declined to 3.1% in 2005. Notwithstanding this decline in cyclical unemployment, the structural adjustment of the economy to higher value-added activities appears to have contributed to the slower trend growth in employment and a consequent rise in the number of structural unemployed Singapore residents (Figure 2). The economy also relies heavily on foreign workers to augment its labor force as well as to plug gaps in human capital requirements of industry (Figure 3).

Table 3. Labor Market, 2002–2005

Sources: Singapore Department of Statistics; Ministry of Manpower.

Source: Labor Force Survey, Ministry of Manpower, Singapore.

Fig. 2. The Long-Term Unemployment in Singapore (%), 2001–2005.

Source: Ministry of Manpower, Singapore.

Fig. 3. Cumulative Employment Change for Singapore Economy by Local and Foreign Workers, 1988–2005.

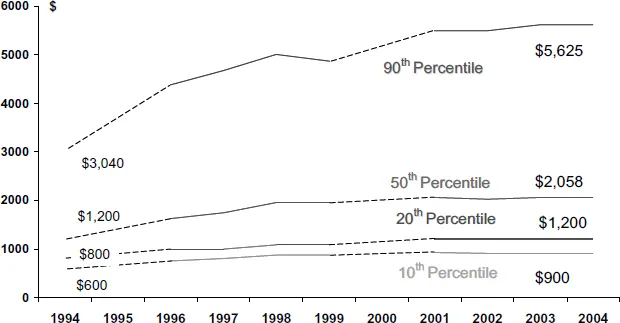

The structural changes in the economy have also created new challenges in terms of widening income gap in the economy. The income of lower 20th percentile appears to have stagnated while that of the top 10th percentile has risen markedly. As with many other countries that have embraced the forces of globalization, this widening income gap presents some important challenges that need to be addressed by policymakers (Figure 4).

Source: Report of the Ministerial Committee on Low Wage Workers.

Fig. 4. Gross Monthly Income of Full-Time Employed Residents, 1994–2004.

1.3.Unit Labor and Business Costs

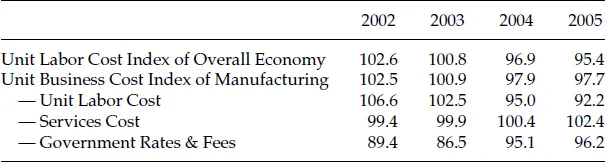

Table 4 summarizes recent trends in unit labor cost (ULC) for the Singapore economy. There appears to be a declining trend between 2002 and 2005. Labor costs form the highest proportion of overall business cost. Consequently, there is a similar declining trend in the unit business cost (UBC) index of manufacturing. However, the cost of services and government rates and fees have been rising, implying the UBCs have not been declining as sharply as ULCs.

Table 4. Indices of Unit Labor and Unit Business Costs for Singapore Economy (2000 base year)

Source: Singapore Department of Statistics.

1.4.Development Strategies

While the openness of the Singapore economy makes it imperative that that ULCs are kept at a competitive level, in the new global economy, comparative advantage is based increasingly on knowledge and creativity than on traditional factor inputs. Entrepreneurship is the conduit between investments in knowledge and economic growth (Audretsch, 2003). There is in fact a fairly new and growing body of econometric evidence which suggests that entrepreneurship is a key determinant of economic growth in a knowledge-based economy. The Singapore government has long recognized the importance of nurturing local entrepreneurship. For instance, the city state’s Minister for Manpower, Lee Boon Yang, has noted:

Accordingly, the Singapore government has forged a commitment to create an environment conducive for entrepreneurial activity and fostering a culture of learning and experimentation. In this regard, it has offered a number of targeted incentives to promote it, especially in the area of high technology (i.e. so-called “technopreneurship”).2

While developing local entrepreneurship is of importance, there is also a need to maximize benefits from foreign investments (Chia, 1992). Foreign multinational corporations (MNCs) bring with them state of the art technology and access to global networks. Greater attention has been placed on strengthening the base of small and medium local enterprises (SMEs) and create and strengthen strategic partnerships and skill linkages between SMEs and MNCs by promoting local sourcing, sub-contracting and technological and R&D spillovers and capabilities (also see Hu and Shin, 2002).

Since the late 1980s, and especially the 1990s, the Singapore government has undertaken an aggressive strategy of building up its external wing by investing heavily in regional and extra regional trading partners (Yeung, 2000). The government remains committed to developing a breed of world-class companies which have a global reach. The government-linked companies (GLCs) are viewed as the “primary instruments through which the state inaugurates the regionalization drive” (Yeung, 2000, p. 21). The Business Times of Singapore (July 2002) makes the following observation about GLCs:

The government, through Temasek Holdings, has significant equity in many of Singapore’s largest companies in vast areas of the economy including port and marine, shipping and logistics, banking&financial services, real estate, airline, telecommunications and media, power and utilities.3

While acknowledging the world-class technocratic capabilities of the Singapore government, Bhaskaran (2003) suggests that the state’s role in Singapore might have become more of a liability and needs to be rolled back in certain areas. In particular, he argues that the government intervention in terms of its ownership and management of the majority of land and other critical resources has distorted relative prices, while the domination of GLCs in local economic activity has curbed private sector initiative by pre-empting local business opportunities. In similar vein, the IMF (2000) makes the following observation:

The Singapore government is clearly cognisant of these assessments. They have recognized that while there was a need for strong role of the state in the early stages of growth to address market failures in the economy, the role of the state in economic developmen...