![]()

Chapter 1

Enhancing Routing Performance in

Mobile Wireless Sensor Networks

through the Use of Controlled

Mobility

Nicolas Gouvy1,2, Nathalie Mitton2 and David Simplot-Ryl2

1 Université Lille 1, 2 Inria Lille – Nord Europe, France

Abstract. Node mobility has long been considered as a hazard in wireless sensor networks, causing a degradation of performance or even persistent routing failures. The advance of technology has made possible a new vision in which mobility allows the improvement of performances and new applications. In this chapter, we focus on some of the contributions that take advantage of controlled mobility in wireless sensor networks to improve message delivery performances.

1.1 Introduction

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSN) are sets of a handful to thousands of sensors communicating through the radio medium in a multi-hop fashion. Each sensor embeds a low-power processor with limited computing and memory capabilities, a radio device and sometimes a localization device. It is essential for the nodes to collaborate in order to route data in a reliable and energy-efficient way to a given destination. The limited energy and computing or memory capabilities of a node and the dynamic nature of wireless links impose extra difficulties in the design of efficient routing protocols. Moreover, in WSN, routing tables is subject to multiple and rapid modifications due to the dynamic nature of the topology (unreliable and unstable wireless links, mobile nodes, etc). Hence traditional network routing protocols are not compliant with energy and dynamic constraints as they rely on large and quite static routing tables stored in memory. Routing protocols for WSN are conceived with those constraints in mind tempering energy overhead, delay and complexity. A new approach in routing in WSN is to introduce controlled mobility enabled sensors. In other words, one has the possibility to relocate one or several nodes in order to modify the topology to save energy. Results in [12] show that deploying resourceful mobile devices in a WSN provides better results in terms of energy consumption than the traditional density increasing.

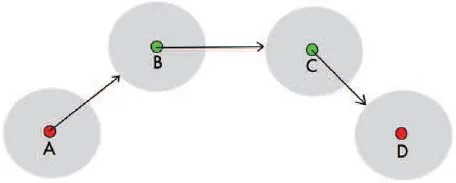

Fig. 1.1 Node A has a message for node D. A uses intermediates nodes B and C to route the message. Arrows represents node trajectories while the disk represents nodes radio range.

To the best of our knowledge, the first paper to use controlled mobility in order to improve routing performance is [8]. In this paper, authors consider the routing in a mobile network, where every node follows a different trajectory. In this kind of network, mobile nodes motions and locations are predictable or estimated with high accuracy by every node at any time for every node according to some known functions. Hence, authors propose an algorithm called Optimal Routing Path which makes the emitting mobile node compute a moving routing path over moving nodes up to the destination (Source routing). Optimal Routing Path is different from previous routing algorithms as it takes account of the possibility for each mobile node to deviate slightly - on purpose - from its trajectory. This temporary deviation aims to make possible message forwarding which would be impossible otherwise because of too short radio-range. Using the global knowledge of nodes movement and the possibility to modify every nod trajectory, Optimal Routing Path returns the shortest time strategy to route a message between two mobile nodes.

Figure 1.1 illustrates a use of Optimal Routing Path algorithm. The network is composed of four mobiles nodes A, B, C and D. A has a message for D which is outside its radio range. Moving directly to D would require a high energy consumption for A. Consequently, A uses its knowledge of motions at dispatch times for all network nodes to computethe moving routing path from A to D. According to the algorithm, A approaches B and forwards the message to it. B behaves the same towards C which moves directly to D and delivers the message.

Still, assuming that every node has a full knowledge of the location and movement of all other nodes in the network makes this approach hardly possible in wireless sensor networks in which devices are constraint in terms of memory and computing capacities.In order to overcome this strong assumption, a new routing paradigm has been proposed called Message Ferrying. Message Ferrying assumes that only some nodes are mobile and only requires the knowledge of mobile nodes.

1.2 Message Ferrying

Message Ferrying is a wireless routing paradigm in which a mobile node called a ferry travels inside the network following a predefined trajectory. The ferry can thus receive messages and physically carry them to another part of the network. Hence, this paradigm supposes a network where there are at least two different kinds of nodes : the message ferries (or ferry for short) and the other nodes. Although ferries and other nodes can have different hardware specifications, the differentiation criteria is that the ferry only has mobile routing purpose while the other nodes can have other activities. This paradigm differs from Opportunistic routing since Message Ferrying is proactive and non random : the message ferry will move on a defined path whatever the network activity is.

Message Ferrying has been introduced in [13] in order to improve or create connectivity in partitioned network. The ferry route design is of critical importance. It has to reduce the network latency the ferry introduces. The latency requires nodes to have enough memory to buffer the data between ferry passages. Otherwise nodes or even the ferry would have to discard data. This design is known to be an NP-Hard problem and can only be approximated.

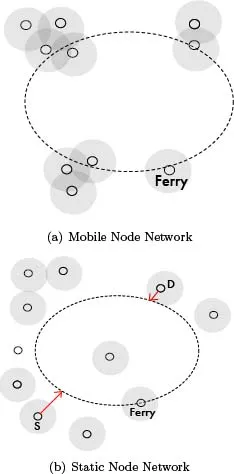

In case of a static network such as in Fig. 1.2(a), the ferry is used to create a fully connected network. The use of a mobile ferry allows nodes to communicate with each others despite the network partition. Authors in [13] proposed an algorithm for static networks. The computation of the ferry route is made by using the traveling salesman problem (TSP) resolution algorithm over all the nodes tuned in order to reduce the total delay of the ferry route. The route is then adapted in order to satisfy bandwidth criteria. This approach makes the ferry a message carrier traveling from rendezvous point to rendezvous point. On these points, it stores messages to route, carries them to the corresponding rendezvous point before forwarding.

Fig. 1.2 Message Ferrying in action. The ferry moves accordingly to its trajectory, carrying messages physically.

In mobile network, the ferry can avoid long travels for mobile nodes. This ferry-in-a-mobile-network case is addressed in [14]. In this work, the authors distinguish two different cases. The Node Initiated Message Ferry Scheme (NIMFS), which is illustrated in Fig. 1.2(b), and the Ferry Initiated Message Ferry Scheme (FIMFS).

In NIMFS, if a node S has a message for D, instead of traveling up to D, node S heads to the ferry on its trajectory and forwards it the message in a short range manner. The ferry then carries the message on its route without making changes on its trajectories. Finally, when D is detected by the ferry, the message is forwarded.

In FIMFS, when a node needs to send a message, it warns the ferry which makes a detour to join this node. In other words, the ferry actively leaves its trajectory to get the packet in a short range manner. Once the ferry has retrieved the packet, its route is recomputed in order to deliver the message. The route computation in FIMFS is one of the two following heuristics: either it always moves towards the Nearest Neighbor, or it uses a similar approach to the one in [13] computing a TSP path tuned to minimize the expected message dropping.

Numerous approaches have been proposed in order to optimize the route of the ferry in the Message Ferrying scheme. A major advance [15] is to consider the introduction of multiple ferries and not only one. As a generalized problem, the route computation for multiple ferries is also NP-hard. Multiple cases have been considered with or without communications between the multiple ferries. Nevertheless, the use of controlled mobility in routing case is now considered for networks in which all the nodes are controlled mobility enabled and are all considered in order to make a multihop routing while adapting network topology to the network activity.

1.3 Network Connectivity Guarantee

The hypothesis of a complete network on which we can relocate every node on the source destination path in order to both optimize network topology and increase delivery rate is not without consequences. Network connectivity has to be maintained. In other words, it means that there must be one (or multi)-hop path between each node of ...