Rechargeable Sensor Networks: Technology, Theory, And Application - Introducing Energy Harvesting To Sensor Networks

Introducing Energy Harvesting to Sensor Networks

- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Rechargeable Sensor Networks: Technology, Theory, And Application - Introducing Energy Harvesting To Sensor Networks

Introducing Energy Harvesting to Sensor Networks

About this book

The harvesting of energy from ambient energy sources to power electronic devices has been recognized as a promising solution to the issue of powering the ever-growing number of mobile devices around us.

Key technologies in the rapidly growing field of energy harvesting focus on developing solutions to capture ambient energy surrounding the mobile devices and convert it into usable electrical energy for the purpose of recharging said devices. Achieving a sustainable network lifetime via battery-aware designs brings forth a new frontier for energy optimization techniques. These techniques had, in their early stages, resulted in the development of low-power hardware designs. Today, they have evolved into power-aware designs and even battery-aware designs.

This book covers recent results in the field of rechargeable sensor networks, including technologies and protocol designs to enable harvesting energy from alternative energy sources such as vibrations, temperature variations, wind, solar, and biochemical energy and passive human power.

Contents:

- Wind Energy Harvesting for Recharging Wireless Sensor Nodes: Brief Review and a Case Study (Yen Kheng Tan, Dibin Zhu and Steve Beeby)

- Rechargeable Sensor Networks with Magnetic Resonant Coupling (Liguang Xie, Yi Shi, Y Thomas Hou, Wenjing Lou, Hanif D Sherali and Huaibei Zhou)

- Cross-Layer Resource Allocation in Energy-Harvesting Sensor Networks (Zhoujia Mao, C Emre Koksal and Ness B Shroff)

- Energy-Harvesting Technique and Management for Wireless Sensor Networks (Jianhui Zhang and Xiangyang Li)

- Information Capacity of an AWGN Channel Powered by an Energy-Harvesting Source (R Rajesh, P K Deekshith and Vinod Sharma)

- Energy Harvesting in Wireless Sensor Networks (Nathalie Mitton and Riaan Wolhuter)

- Topology Control for Wireless Sensor Networks and Ad Hoc Networks (Sunil Jardosh)

- An Evolutionary Game Approach for Rechargeable Sensor Networks (Majed Haddad, Eitan Altman, Dieter Fiems and Julien Gaillard)

- Marine Sediment Energy Harvesting for Sustainable Underwater Sensor Networks (Baikun Li, Lei Wang and Jun-Hong Cui)

- Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks in the Smart Grid (Melike Erol-Kantarci and Hussein T Mouftah)

- Energy-Harvesting Methods for Medical Devices (Pedro Dinis Gaspar, Virginie Felizardo and Nuno M Garcia)

Readership: Graduates, researchers, and professionals studying/dealing with networking, computer engineering, parallel computing, and electrical & electronic engineering.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Wind Energy Harvesting for Recharging Wireless Sensor Nodes: Brief Review and A Case Study

University (ERI@N), Singapore

[email protected],

[email protected]

United Kingdom

1. Introduction

2. Wind Energy Harvesting from Wind Turbines

2.1. Description of technique

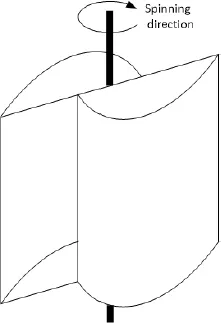

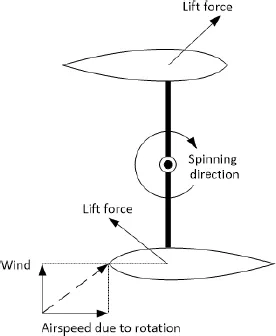

2.1.1. Savonius wind turbine

2.1.2. Darrieus wind turbine

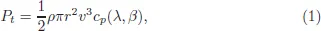

2.1.3. Maximum available power

2.1.4. Efficiency

Table of contents

- Cover

- HalfTitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Wind Energy Harvesting for Recharging Wireless Sensor Nodes: Brief Review and A Case Study

- 2. Rechargeable Sensor Networks with Magnetic Resonant Coupling

- 3. Cross-Layer Resource Allocation in Energy-Harvesting Sensor Networks

- 4. Energy-Harvesting Technique and Management for Wireless Sensor Networks

- 5. Information Capacity of an AWGN Channel Powered by an Energy-Harvesting Source

- 6. Energy Harvesting in Wireless Sensor Networks

- 7. Topology Control for Wireless Sensor Networks and Ad Hoc Networks

- 8. An Evolutionary Game Approach for Rechargeable Sensor Networks

- 9. Marine Sediment Energy Harvesting for Sustainable Underwater Sensor Networks

- 10. Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks in the Smart Grid

- 11. Energy-Harvesting Methods for Medical Devices

- Index