- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Forcing For Mathematicians

About this book

Ever since Paul Cohen's spectacular use of the forcing concept to prove the independence of the continuum hypothesis from the standard axioms of set theory, forcing has been seen by the general mathematical community as a subject of great intrinsic interest but one that is technically so forbidding that it is only accessible to specialists. In the past decade, a series of remarkable solutions to long-standing problems in C * -algebra using set-theoretic methods, many achieved by the author and his collaborators, have generated new interest in this subject. This is the first book aimed at explaining forcing to general mathematicians. It simultaneously makes the subject broadly accessible by explaining it in a clear, simple manner, and surveys advanced applications of set theory to mainstream topics.

Contents:

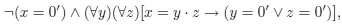

- Peano Arithmetic

- Zermelo–Fraenkel Set Theory

- Well-Ordered Sets

- Ordinals

- Cardinals

- Relativization

- Reflection

- Forcing Notions

- Generic Extensions

- Forcing Equality

- The Fundamental Theorem

- Forcing CH

- Forcing ¬ CH

- Families of Entire Functions*

- Self-Homeomorphisms of βℕ \ ℕ, I*

- Pure States on B ( H )*

- The Diamond Principle

- Suslin's Problem, I*

- Naimark's problem*

- A Stronger Diamond

- Whitehead's Problem, I*

- Iterated Forcing

- Martin's Axiom

- Suslin's Problem, II*

- Whitehead's Problem, II*

- The Open Coloring Axiom

- Self-Homeomorphisms of βℕ \ ℕ, II*

- Automorphisms of the Calkin Algebra, I*

- Automorphisms of the Calkin Algebra, II*

- The Multiverse Interpretation

Readership: Graduates and researchers in logic and set theory, general mathematical audience.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1Peano Arithmetic

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Titlepage

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Peano Arithmetic

- 2. Zermelo-Fraenkel Set Theory

- 3. Well-Ordered Sets

- 4. Ordinals

- 5. Cardinals

- 6. Relativization

- 7. Reflection

- 8. Forcing Notions

- 9. Generic Extensions

- 10. Forcing Equality

- 11. The Fundamental Theorem

- 12. Forcing CH

- 13. Forcing-CH

- 14. Families of Entire Functions*

- 15. Self-Homeomorphisms of βN \ N, I*

- 16. Pure States on B(H)*

- 17. The Diamond Principle

- 18. Suslin’s Problem, I*

- 19. Naimark’s Problem*

- 20. A Stronger Diamond

- 21. Whitehead’s Problem, I*

- 22. Iterated Forcing

- 23. Martin’s Axiom

- 24. Suslin’s Problem, II*

- 25. Whitehead’s Problem, II*

- 26. The Open Coloring Axiom

- 27. Self-Homeomorphisms of βN \ N, II*

- 28. Automorphisms of the Calkin Algebra, I*

- 29. Automorphisms of the Calkin Algebra, II*

- 30. The Multiverse Interpretation

- Appendix A Forcing with Preorders

- Exercises

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Notation Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app