- 632 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Antioxidants And Stem Cells For Coronary Heart Disease

About this book

This book covers two known controversial topics — antioxidants and stem cells as therapies to treat coronary heart disease. Aiming to provide college-educated but not scientifically trained readership with a wealth of information about these two cutting-edge technologies, Antioxidants and Stem Cells for Coronary Heart Disease is written with minimum scientific terminology. Basic science studies and clinical trials regarding stem cells and antioxidants are discussed and peppered with anecdotes to make them understandable and entertaining to the laymen.

Contents:

- Part I:

- The French Paradox

- LDL Oxidation — Briefly

- Acetylation of LDL

- Free Radicals

- The Oxygen Paradox

- Retrolental Fibroplasia from 1956 to 1972: The Quiet Time

- The Second Epidemic of Retrolental Fibroplasia: 1972–20??

- Cytokines and Chemokines

- LDL Oxidation by Free Radicals — In Detail

- Two Other Ways to Oxidize LDL: Lipoxygenase and Nitric Oxide

- What is the Raison d'être for Oxidized LDL?

- Fatty Streaks and Foam Cells

- Embryonic Stem Cells

- Adult Stem Cells

- Transgenic Mice

- Part II:

- Treatment of Coronary Heart Disease with Antioxidants: An Introduction

- The Mediterranean Diet

- Acute Myocardial Infarctions in Japan and Norway from 1910 to 1950

- Wine, Beer, and Spirits as Antioxidants

- A Perspective on Antioxidant Vitamins for the Treatment of Coronary Heart Disease

- Vitamin A

- The Thalidomide Saga

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin E

- Do Combinations of Antioxidant Vitamins Work Better than Individual Vitamins in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease?

- A Requiem

- Molecular Markers, Reporter Genes and Suicide Genes

- Stem Cells for the Heart: Hype or Hope?

- The Prizefight

- Brainbow

- Cre/Lox: A Cut-and-Paste Method of Gene Swapping Without a Mac or PC and a New Scientific Term with Vast Significance

- Bacteriophage, Transgenic Mice and Transgenic Marmosets

- Phage Geometry and Soccer Balls

- Euler's Formula

- E = mc 2 and Einstein's Brain

- The Manhattan Project and Its Connection with Albert Einstein

- A Gadget, a Little Boy and a Fat Man

- Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón Y Cajal: Bitter Rivals to The End

Readership: College-educated general public and non-scientists who are interested in the topic of antioxidants and stem cells.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Antioxidants And Stem Cells For Coronary Heart Disease by Philip B Oliva in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biowissenschaften & Wissenschaft Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

BiowissenschaftenSubtopic

Wissenschaft Allgemein1

THE FRENCH PARADOX

Three culturally distinct races — the French, the Japanese, and the North American (as well as Greenlandic) Eskimos — share a medical blessing: they have fewer heart attacks than the natives of many other countries. Their coronary resistance resides in what they eat and/or drink. In the case of the French, although they eat a lot of rich food, they also drink a lot of (red) wine. In the case of the Japanese, they eat a lot of low-cholesterol seafood and drink a lot of sake and beer. In the case of the Eskimos (or the Inuita), they eat a lot of marine life — fish, whale, and seal1 — and drink a lot of homemade or distilled spirits.

These dietary, cultural or medical facts spawned curiosity about compounds in food and/or alcoholic beverages that might protect against coronary heart disease. Advancement of the concept that low-density lipoprotein (LDL), the principal carrier of cholesterol in the blood, must be oxidized before it becomes dangerous2 has led to intensive research on ways to slow or prevent its oxidation. And after wine was discovered to have antioxidant properties in 1993,3 scientists conjectured that alcohol might link the three dissimilar cultures and their shared resistance to heart disease.

A trickle of publications regarding antioxidants and coronary heart disease appeared in the medical literature in the mid-1990s, and has now grown into a sea of papers throughout the scientific literature. The published material records the findings of a considerable body of research concerning the clinical use of antioxidants to prevent or treat coronary heart disease, and, to an even greater extent, it registers the results of an extraordinary volume of research by basic scientists pertaining to the biochemistry of how LDL is oxidized. The last chapter of the antioxidant story has yet to be written. When it finally is put into print, it will be a memorable one. But, even today, the murky waters that encircled antioxidants just a few years ago have become much clearer. It’s a tale worth telling even though its ending is still up in the air.

In the Beginning. . .

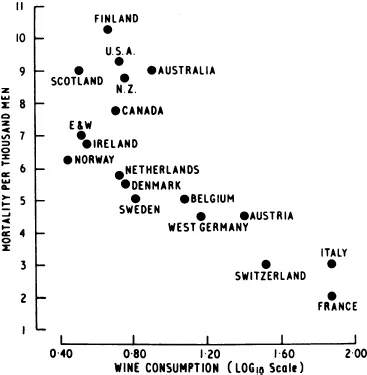

It all began in 1979, when a French physician published a paper in England’s leading medical journal, showing that the mortality rate due to coronary heart disease (CHD) was lower in France — where wine consumption was higher — than in 17 other countries, including the U.S. (Fig. 1.1).4

At about the same time as the “French paradox” was being recognized, a group of researchers in the Department of Molecular Genetics at the University of Texas (in Dallas) came upon another seeming contradiction. They discovered that “bad cholesterol” (i.e. low-density lipoprotein)b was taken up by cells lining the walls of blood vessels at a rate too slow to result in any significant accumulation of cholesterol within their cytoplasm.c Yet blood vessels critically narrowed by cholesterol deposits had accumulated a huge amount of the lipid — a fat that, by definition, is not soluble in water. The scientists also learned that patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (elevated blood cholesterol level),d an inherited disorder of lipid metabolism leading to blood cholesterol levels often in the range of 400–1,000 mg/dL, similarly had vascular cells that did not take up any bad cholesterol. . .at least when they were incubated in a laboratory with their own blood containing very high levels of cholesterol. They were essentially invulnerable to harmful cholesterol. Yet the same type of cells clearly took up cholesterol when they were within the human body in direct contact with circulating blood, leading to severe atherosclerosise even in the absence of any other risk factors. To explain the paradox of how fat-filled cells in the lining of such cholesterol-narrowed blood vessels became overloaded with the lipid in spite of taking it up too slowly in the laboratory to result in a buildup, and to account for why LDL was also taken up too slowly to cause atherosclerosis — even in individuals without a genetic predisposition to develop the disease — it was suggested that LDL must be changed into a form that could both penetrate cells and be taken up more rapidly than “native” LDL.f Only then could massive deposits of LDL occur throughout the body. In 1984, that related form was shown to be “oxidized” LDL.5

Fig. 1.1. The inverse relationship between mortality from coronary heart disease and wine consumption among men aged 55–64 in 17 countries.

(Source: Reproduced with permission from the publisher.) Reference 4.

References

| 1. | Bang HO, Dyerberg J, Hjorne N. (1976) The composition of foods consumed by Eskimos. Acta Med Scand 200: 69–73. |

| 2. | Steinberg D, Parthasarathy S, Carew TE, Khoo JC, Witzum JL. (1989) Beyond cholesterol: modifications of low-density lipoprotein that increase its atherogenicity. N Engl J Med 320: 915–924. |

| 3. | Frankel EN, Kanner J, German E, Parks E, Kinsella JE. (1993) Inhibition of oxidation of low density lipoprotein by phenolic substances in red wine. Lancet 341: 454–457. |

| 4. | St Leger AS, Cochrane AL, Moore F. (1979) Factors associated with cardiac mortality in developed countries with particular reference to the consumption of wine. Lancet 313: 1017–1020. |

| 5. | Steinbrecher UP, Parthasarathy S, Leake DS, Witztum JL, Steinberg D. (1984) Modification of low density lipoprotein by endothelial cells involves lipid peroxidation and degradation of low density phospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 3883–3887. |

a The term “Eskimo” means “he who eats (meat) raw.” “Inuit” translates best as “real people.” Most North American and Greenland Arctic Circle dwellers prefer the latter term.

b Low-density lipoprotein is a large compound made up of 22,000 cholesterol molecules and 2616 fatty acid molecules, which together constitute 79% of the compound’s weight, attached to one protein molecule accounting for the remaining 21% of its weight. The lipoprotein is the principal carrier of cholesterol in the bloodstream. Cholesterol, being a lipid, is not soluble in the watery plasma, which constitutes 55% of the blood volume. Therefore, a carrier is needed to transport cholesterol from its origin in the liver or digestive tract to its destination at cells throughout the body. The modifier “low-density” refers to the compactness of the lipoprotein, expressed as the ratio of mass to volume. In the case of cholesterol-carrying lipoproteins, such as LDL and HDL, the units of density are g/cm-1, with 1.063 g/cm-1 separating low- from high-density lipoproteins. The range is 1.019–1.210 g/cm-1.

c Such cells are known collectively as the intima — the innermost coat of arteries and veins — though only the intima of arteries takes up cholesterol. The single layer of intimal cells in direct contact with blood is called the endothelium.

d Individuals with this rare condition affecting one in one million persons inherit a defective gene governing LDL receptors (to be discussed in Chap. 3) from each parent. The defective gene usually leads to a very high cholesterol level (600–1000 mg/dL), which, in turn, results in a heart attack during childhood.

e The term “atherosclerosis” refers to the disease process that causes the deposition of LDL in arteries. It describes the mushy consistency of cholesterol in the wall of arteries during the early and intermediate stages of the disease. The term comes from the Greek words “athero” (meaning “porridge”) and “sclerosis” (meaning “hardening”). The term “arteriosclerosis” refers to the more advanced stage of the disease, when the arteries become brittle. That stage of the disease process is often not reversible. “Arteriosclerosis” comes from the Greek words “arterio” and “sclerosis” (meaning “artery” and “hardening,” respectively). The phrase “hardening of the arteries” is often applied to such vessels. In this book, “Atherosclerosis” is used almost exclusively to discuss (for the most part) the early and mid-phases of the disease.

f The term “native LDL,” rather than “natural LDL,” is traditionally used in science because LDL does not occur “naturally,” i.e, it does not occur in nature. The adjective “native” is used to indicate that the LDL exists in its original (i.e, its unoxidized) form. Native (unoxidized) LDL is harmless. It does not damage cells until it undergoes oxidation.

2

LDL OXIDATION — BRIEFLY

But just what is “oxidized LDL”? How does native (unoxidized) LDL become oxidized? How does its oxidation accelerate the deposition of cholesterol in the intima of arteries? How do antioxidants affect those deposits, particularly those in the coronary arteries? And, perhaps most importantly, can taking an antioxidant prevent a buildup — and perhaps, one day, a heart attack?

We bandy the term “oxidized cholesterol” around as if it were a well-known compound, a common dietary substance — like flour or rice. We use the term “oxidation” (with reference to LDL) as if it were a straightforward process — like boiling an egg. We even throw around phrases related to oxidized LDL — such as “free radicals,” “omega-3 fatty acids,” “cytokines,” “superoxide ions,” and “trans fats” — at cocktail parties and during dinner table conversations as if we were talking about last Sunday’s NFL games or today’s stock market activities. But our ease with these technical terms belies the complexity of the LDL oxidation process.a That process will be put in a nutshell to encourage continued reading, before ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Part I

- Part II