![]()

CHAPTER 1

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES FOR KNEE JOINT REPAIR

WILLIAM ROSSY, CARLOS UQUILLAS and ERIC J. STRAUSS

Division of Sports Medicine NYU Hospital For Joint Diseases New York, NY

Introduction

As the number of people participating in organized sports has increased in recent years, so has the incidence of sports related injuries. This increased participation in organized athletics has been found in school children, all the way up to “weekend warrior” athletes. It has been estimated that 30 million children in the United States participate in organized sports.1 In 2009, Darrow et al. specifically looked at high school athletes and found the incidence of sports-related injuries approached 40% of all nonfatal, unintentional injuries among high school youth treated in emergency departments.2 Of all the injuries reported in their cohort, it was found that the most commonly injured body site was the knee, which accounted for 29% of total cases. Other injury types included in this study were accidents involving the head (6.8%), shoulder (10.9%), wrist (4.3%), finger/hand (7.9%), and ankle (12.3%). It was found that of the reported injuries that required surgical intervention, more than half (53.9%) involved the knee.

Knee injuries in sports related accidents account for millions of visits to emergency departments each year. The most common knee injuries sustained by athletes include anterior or posterior cruciate ligament ruptures, medial or lateral meniscal injuries, cartilage injuries, and collateral ligament injuries. These injuries have a myriad of different treatment strategies with the goal of returning the patient to their prior level of function and sport. This chapter will focus on the surgical management of these pathologies. We will specifically discuss epidemiology, anatomy, mechanism of injury, diagnostic work up, surgical options, and surgical outcomes.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

Anatomy

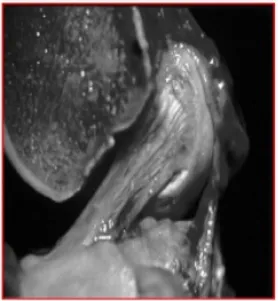

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) originates from the medial wall of the lateral femoral condyle and courses anteriorly and medially to insert into the tibial articular surface. It is composed of two functional bundles, the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles, named based on their tibial insertion sites. The specific locations of these attachments plays an important role in the biomechanics of the ACL. Due to the large attachment sites, the ACL allows different portions of the ligament to tighten at various degrees of knee flexion. The femoral attachment site is located on the posteromedial surface of the intercondylar notch on the lateral femoral condyle. The attachment is circular, spanning an area of approximately 113 mm2. The tibial attachment is located approximately 15 mm from the anterior border of the tibial articular surface, covering an area of about 136 mm2. The mid-substance cross-sectional area is approximately 40 mm2 (Figure 1).3

Biomechanics

The function of the ACL is to provide primary anteroposterior stability and secondary rotatory and coronal stability to the knee joint.4,5 There is age related loss of strength of the ACL, with older ACLs failing with lower loads than younger ACLs.6,7 The ACL withstands a wide range of forces ranging from 100 N during passive range of motion exercises to about 1700 N during cutting, and pivoting maneuvers.8 The maximal tensile load is 2160 N.6

Epidemiology

The ACL is the most commonly injured ligament in the knee. It is most commonly injured during sports related activity with only a minority of ACL injuries occurring in high-energy trauma or activities of daily living.8 ACL injuries represent approximately 40–50% of all knee ligament injuries. Patients report hearing or feeling a pop at the time of injury 70% of the time and almost all patients notice swelling of the knee within 24–48 h of injury. The sports most commonly associated with ACL injuries are those that involve cutting or pivoting, namely soccer and skiing. Female athletes have a two to four fold higher risk of ACL injury than males.9

Fig. 1. Sagital view of cadaver knee showing anteromedial and posterolateral bundle of ACL. ACL runs from medial aspect of lateral femoral condyle to tibial spine.

Pathoanatomy

The majority of ACL injuries are complete disruptions. In skeletally mature patients, the most common site of the disruption is midsubstance or along the femoral insertion of the ACL. In skeletally immature patients, avulsion off the tibial attachment with or without a piece of bone is more commonly seen.

Work up

The first step to diagnose and treat an ACL injury is a thorough history and physical examination. Any patient with knee swelling after a sports related knee injury should be evaluated for possible ACL tear. Diagnosis of chronic ACL injury may involve a history of recurrent knee pain, mechanical symptoms from a secondary meniscal tear or instability. A thorough history may be difficult in the acute setting due to pain and swelling associated with the injury. Patients with acute ACL injury present with a large effusion, related to hemarthrosis secondary to bleeding from the vessels within the ligaments synovial sheath. Palpation of all bony prominences should be carefully performed with special attention to the femoral origin of the medial collateral ligament. Patellar apprehension must be noted, as acute patellar dislocations often present with a similar history as ACL injury. The quadriceps and patellar tendons should also be examined as injuries to these structures may be confused with ACL injuries. Special testing for ACL injuries include the Lachman test, anterior drawer test and pivot shift test. The Lachman test is the most useful in the initial diagnosis. A sense of increased tibial translation or a lack of a solid endpoint are indicative of ACL injury. The pivot shift test is pathognomonic for ACL injury. The test begins with the knee in full extension, and the knee is the flexed while applying a valgus moment. As the iliotibial band (ITB) passes posterior to the axis of knee rotation at approximately 15° of knee flexion, the tibia (which is subluxated anteriorly on the femur) reduces with a visible shift at the lateral joint line. This should always be compared with the contralateral side, where a physiologic pivot shit or pivot glide may occasionally be present.

Imaging

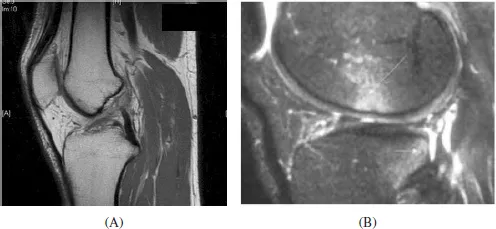

Radiographic evaluation of a patient with a suspected ACL injury includes plain radiographs of the affected knee to rule out fracture in the acute setting. Associated injuries that may be identified on plain imaging include a Segond fracture10 (lateral capsular avulsion) and tibial eminence avulsion fractures in skeletally immature patients. Additionally, the presence of open physes is of particular importance as this can impact the surgical treatment approach. MRI is not required for the diagnosis of ACL injury, but it is useful for assessing for associated injuries to the meniscus, other ligaments, the articular surface and for the presence of subchondral bone marrow edema lesions and fractures. The characteristic edema pattern seen on MRI with bone marrow lesions present within the posterolateral tibial plateau and the central lateral femoral condyle correspond to the pivot-shift type translational event that occurs during injury (Figure 2). In the coronal and sagital MRI images, disruptions in the normal black ACL fibers signify ACL injury.

Fig. 2. (A) T1 weighted sagittal MRI showing ruptured ACL. (B) T2 weighted sagittal MRI showing characteristic bone edema seen after ACL tear.

Treatment

ACL reconstruction is indicated in active patient populations who are involved in cutting, pivoting and twisting activities. The goal of ACL reconstruction is to return functional stability of the knee to allow for return to full activity as well as to prevent further damage to the menisci and chondral surfaces that can lead to early-onset arthritis. Elderly or more sedentary individuals may have a good outcome with non-surgical management. Non-surgical management involves rehabilitation to strengthen the hamstrings (HSs) and quadriceps, as well as proprioceptive training. Activity modification is an important part of non-surgical management. Contraindications to surgery include: lack of quadriceps function, significant comorbidities, or inability to tolerate surgery or the necessary post-operative rehabilitation required.

The success rate of ACL reconstructions has reached up to 90% with respect to post-operative knee stability and patient satisfaction.11 Graft choice varies from surgeon to surgeon. Multiple factors are involved in the choice of ACL reconstruction graft type, including biomechanical properties, biologic incorporation, associated donor site morbidity, graft tensioning issues, graft fixation options, and clinical outcome. Available graft options can be divided into two main classes: autograft and allograft. In these classes, autograft options include bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB), quadriceps tendon, quadrupled semitendinosus and gracilis HS tendon. Allograft options include quadriceps, Achilles, tibialis anterior or posterior, BPTB, and HS. The gold standard is thought to be BPTB autograft due to ease of harvest, comparable structural properties to the native ACL, available rigid fixation techniques, bone to bone rather than soft tisse to bone healing, and a long track record of success.12–14 Graft healing involves both the healing at the graft attachment site as well as the process of graft revascularization and incorporation (termed ligamentization). Grafts containing bone typically resemble fracture healing with bone healing occurring within six weeks. Soft tissue grafts take longer, between eight and 12 weeks to heal into host bone. The process of graft incorporation begins with a period of inflammation in which the graft loses strength and stiffness. This phase is between day 20 and up to 3–6 months after surgery, losing up to 80% of its strength.15 Donor site complications are typically seen with BPTB grafts, include patellar fractures,16 patellar tendon ruptures,17 localized numbness and tendonitis.18 Use of allograft produces decreased donor site morbidity, shorter operative time, preservation of extensor and flexor mechanisms, and ...