![]()

1

Introduction

WHAT IS SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY, EXACTLY?

You may know it when you see it, but how would you define it? Synthetic biology is undoubtedly a new, rapidly growing field that is captivating students and researchers alike. Yet, like life itself, synthetic biology is notoriously hard to define. Though the term “synthetic biology” was coined a century ago, its use only came into vogue one decade ago. This “renaissance” cannot be attributed to any single breakthrough or publication, so why did it occur? How does synthetic biology differ from, for example, the older field of biotechnology that encompasses DNA cloning, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), monoclonal antibodies and protein overexpression? Engineers may emphasize “the development of foundational technologies that make the design and construction of engineered biological systems easier” (Endy, 2005), such as BioBricks™ (Knight, 2003). Alternatively, biologists and chemists wishing to encompass both in vitro and in vivo projects may describe synthetic biology as “the complex manipulation of replicating systems” (Forster and Church, 2007). Still others define synthetic biology in terms of applications where, for example, bioenergy, biomaterials and biosensors are synthetic biology while antibodies and induced pluripotent stem cells are not. The use of engineering principles for biological applications is not new, as evidenced by the long-term success of biotechnology. But what is definitely new versus classical recombinant DNA and PCR is that synthetic biology is much easier and more creative. The parts and techniques are more standardized and cheaper, allowing faster, more modular use with more predictable outcomes based upon more precise measurements of activities. Computer-aided design, analysis and modeling have further hastened progress. These next-generational technologies, together with tagged libraries and inexpensive, rapid, commercial oligodeoxynucleotide/gene syntheses and sequencing, have empowered biology and engineering students and scientists like never before.

THE iGEM OUTBREAK

iGEM is an acronym for international Genetically Engineered Machine and is a worldwide annual competition in synthetic biology for students from secondary and tertiary institutions. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) organized the first competition in 2004 between teams from five universities in the U.S.A. Projects are student-driven and lab work is mostly done during the summer when students and labs are free from classes. iGEM has proven to be one of the most motivational educational methods ever devised, with the competition growing every year to now encompass 230 teams, including 30 teams in a high school division (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 iGEM teams competing at MIT in 2006. Annual iGEM competitions have since expanded to encompass thousands of students worldwide. (Photograph by Randy Rettberg; taken from Wikipedia with permission.)

There is every reason to expect iGEM will continue expanding until it reaches most major educational institutions in the world. In parallel with this infectious, grassroots movement, career opportunities in synthetic biology in industry and academia are ballooning, mandating more defined education in synthetic biology than achievable just through iGEM. Thus, student enthusiasts are teaming up with university administrators to demand the creation of formal courses in synthetic biology, with our full lab course beginning in 2013 as a result. Formal courses complement and differ from iGEM by providing a more rounded education, requiring individual responsibility for knowledge and lab skills, and awarding creditation on an individual basis.

A SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY LAB MANUAL

Even the most highly motivated synthetic biology students in general, and iGEM students in particular, can be pretty raw in their knowledge and require considerable guidance with lab work. And teachers with no prior experience in synthetic biology can be pressed with the daunting task of setting up an entire lab course from scratch. At the time of writing, there are some synthetic biology protocols available online (e.g. see Lab section 4 of Chapter 5), but what is sorely lacking is a lab manual. Here we address this unmet need with three goals:

1. To provide teachers and lab managers with all the information they need to set up and run a synthetic biology lab course that spans from 2 to 5 weeks or more of full-time work;

2. To provide high school students and tertiary institution students and researchers with protocols for lab work; and

3. To provide iGEM students with practical information on setting up and running their own summer project in a host lab.

The underlying philosophy of our lab course design is similar to that of iGEM: to foster learning through student-driven, creative research with cutting-edge methods in small teams. Teams encourage learning through discussions and teamwork, not to mention being a practical way of economizing use of reagents and equipment. Students will not only learn key synthetic biology technology such as BioBrick™ cloning, but also have the opportunity to create their own projects with varying difficulties. Where the course philosophy differs from iGEM is in requiring each individual student to submit their own lab book for assessment and also to take a final exam. Without this individual responsibility, some team members will rely too heavily on other team members or become too specialized, thus failing to learn the important principles and failing to keep up with all aspects of the project. For example, an iGEM computational modeler may not understand operon function.

Just as iGEM teams struggle each year to pick a good project, so did we agonize in selecting a project for the lab course. Key considerations are outlined here as they may be helpful to future iGEM teams and course planners alike.

1. Expensive new equipment should not be required due to budget limitations.

2. In vivo replicating systems are generally easier to engineer in a novel way than in vitro ones. And most synthetic biology is in vivo.

3. Escherichia coli (E. coli) is the best model organism in biology. It is the best characterized, among the simplest and fastest growing, safe, and it is compatible with by far the most BioBrick™ DNA parts (already numbering in the thousands).

4. The use of chromoproteins as easy readouts of gene expression is encouraged. Chemical substrates are not required, neither is the ultraviolet (UV) light that is needed for detecting the related fluorescent proteins such as green fluorescent protein (GFP). Furthermore, the colors can be changed readily by mutagenesis to become lighter, darker or even different colors. The advent of several chromoproteins that can be manipulated easily in E. coli using BioBricks™ is new, and we knew from our iGEM team that students really enjoyed making colored bacteria! For these reasons we selected a chromoprotein expression project for our lab course.

![]()

2

Genes, Chromoproteins

and Antisense RNAs

Use of this manual requires a little basic knowledge in chemistry and biochemistry. Such principles are well covered by many textbooks (see References), including the only textbook on the principles of synthetic biology published at the time of writing (Freemont and Kitney, 2012). The reader is encouraged to consult these textbooks for the structures of biological macromolecules and their functions such as base pairing and catalysis. Nevertheless, it is difficult to find updated practical information in three rapidly evolving fields central to our experimental design: codon bias, chromoproteins and antisense RNAs in E. coli. Before covering these three topics below, some basic aspects of molecular biology directly relevant to synthetic biology and our lab are introduced.

E. coli DNA: CHROMOSOMES,

PLASMIDS AND COPY NUMBER

E. coli is a bacterium growing in our colons and is the only “chassis” organism used in this manual.

Chassis

When the word “chassis” is used in synthetic biology, it simply refers to the organism that will be used to host the synthetic system. The most used and best characterized chassis of them all is E. coli. There are many different strains of E. coli, each having advantages and disadvantages. For cloning and assembly, cloning strains like DH5α are used because they give high transformation frequencies and good plasmid DNA preparations. However, for expressing synthetic devices, a healthier wild-type strain like MG1655 is more suitable than the rather weak and somewhat slower-growing cloning strains. While many synthetic biology standards and assembly methods are chassis independent, others are not (e.g. promoters and codon bias). It is very important to bear this in mind when moving a gene from one chassis into another.

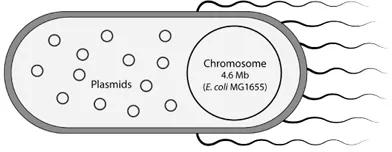

E. coli contains a single, double-stranded, circular, chromosomal DNA molecule of ~4.6 million base pairs encoding ~4400 genes. Some E. coli cells also maintain much smaller, double-stranded, circular DNA molecules of a few thousand base pairs known as plasmid DNAs (Fig. 2).

Plasmid DNA is easier to engineer than chromosomal DNA in many ways. For example, while the copy number of chromosomal DNA per cell is one, the copy number of a plasmid per cell may be anywhere from one to hundreds, depending on the particular origin of replication on the plasmid DNA. Thus one way to increase expression of a gene on a plasmid is to increase the copy number of the plasmid, thereby increasing the number of gene copies per cell.

Fig. 2 E. coli cell containing chromosomal and plasmid DNAs.

Plasmid copy number and compatibility

A plasmid’s host range, compatibility with other plasmids and copy number is determined by its origin of replication. Only one plasmid from each compatibility group can be stable in a strain at a time, so if you want to design a multi-plasmid system (e.g. for our antisense system), the plasmids must come from different compatibility groups. The difference between expressing a certain construct from the bacterial chromosome (~1 copy), from a medium-low copy plasmid (~15 copies) or from a high copy plasmid (500 copies) can be dramatic. To get high enough expression from a low or medium copy plasmid, a strong promoter may be required. However this promoter on a high copy plasmid could give such high expression that it would be toxic to the cell.

COUPLING OF TRANSCRIPTION AND

TRANSLATION IN BACTERIA

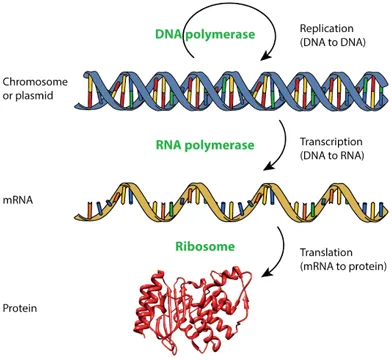

The central dogma of molecular biology dictates that DNA encodes RNA which encodes protein (Fig. 3).

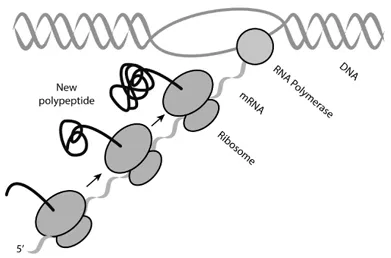

The particular type of RNA that encodes protein is called messenger RNA (mRNA). RNA synthesis from a DNA template is catalyzed by RNA polymerase and is termed transcription. Protein synthesis from an mRNA template is catalyzed by ribosomes and is called translation. In contrast to higher organisms where transcription is physically separated from translation, bacteria couple transcription and translation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 The central dogma of molecular biology. The top and middle structures are taken from Wikipedia with permission.

Fig. 4 Transcription and translation are coupled in bacteria.

A practical implication for synthetic biology of this coupling is that translation can feed back on transcription very rapidly. So rapidly, in fact, that even the initial speed of the translating ribosome can determine whether or not the mRNA it is translating is synthesized completely or terminated prematurely (termed attenuation).

Some RNAs are not translated; these are termed stable RNAs or non-coding RNAs. Examples include the ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) and transfer RNAs (tRNAs) involved in translation, and the small regulatory RNAs engineered as part of the lab course (see below).

PROMOTER AND TERMINATOR

FOR TRANSCRIPTION

Initiation of transcription is determined by protein-DNA interaction...